Dear Life #1: The People I Would’ve Known

“Dear Life” is an ode to the nuance of emotion surrounding death and an exploration of the life we can live when it’s near its end. As I navigate chronic illness and end-of-life care as an aspiring physician, I’ve found that the beauty in healthcare isn’t just saving lives but making life happen.

I killed him. The guilt wracking through me prevailed over my comparatively slight anxiety about spring semester midterms and summer research applications. I sat there while he died.

I called my mother and unloaded the news that her daughter had failed to save a life. She was an ICU nurse— more familiar with death than most— and in that moment, she reassured me that I was not the cause of death for my patient.

It was my second shift at Connecticut Hospice, and I was accompanied by another Yale student, a senior. On the commute, she explained that volunteering at hospice is a relatively lackluster gig. The only responsibility of patient care volunteers is to offer company and conversation to patients — conscious or sedated. Most of the time, patients are sedated to ease pain, so volunteers are expected to sit with them in hopes that their presence is felt. She told me it lacked the excitement and hands-on experience that other clinical opportunities provided.

My own experience has proven that the lack of excitement is exactly what makes it worthwhile. Through witnessing death as both peace and tragedy, I discovered that a “good death” exists, and it’s in moments of stillness that we find it.

The patients I sat with that day were both sedated. The room was large enough to hold four beds, but only two were filled. It smelled like antiseptic and microwavable lunches with the faint scent of “get-well” flowers wafting through the air. The room offered a wall-to-wall window overlooking the Long Island Sound, which took the attention away from the dull paint and focused it onto the still, blue water and wind-blown sailboats.

A sailboat passing Connecticut Hospice in the summer. During peak season, more than twenty sailboats can be seen floating through the water at a time.

When I entered the room, one man was lying down facing the window and the other was positioned with his head raised toward the small television attached to his bed, but both patients were unconscious. Since each bed has its own chair, I chose to sit by the man with his TV on. He looked like he might wake up for a conversation, while the other man looked too peaceful to disturb.

Two hours into my shift, a nurse came in to check on the patients. Neither of them had stirred in the time that I was sitting with them, and I busied myself with schoolwork while the nurse performed her assessments. When she got to the patient who had been lying down, she lingered at his body for a few too many seconds to be able to hide the truth.

“I think he’s gone,” she whispered.

The shoreline of Connecticut Hospice in Branford, CT, where Yale students typically volunteer.

Growing up, death demanded my fear and limited my freedom. My mother, occasionally overbearing, scolded me for reckless adventures through local forests and neighborhood streets and warned me against driving at night because we can’t control others’ decisions. Death took the people that we loved without our permission, so it was our responsibility to ensure it couldn’t take more than that. I was raised to believe death was tactless, greedy, and paralyzing — no more, no less.

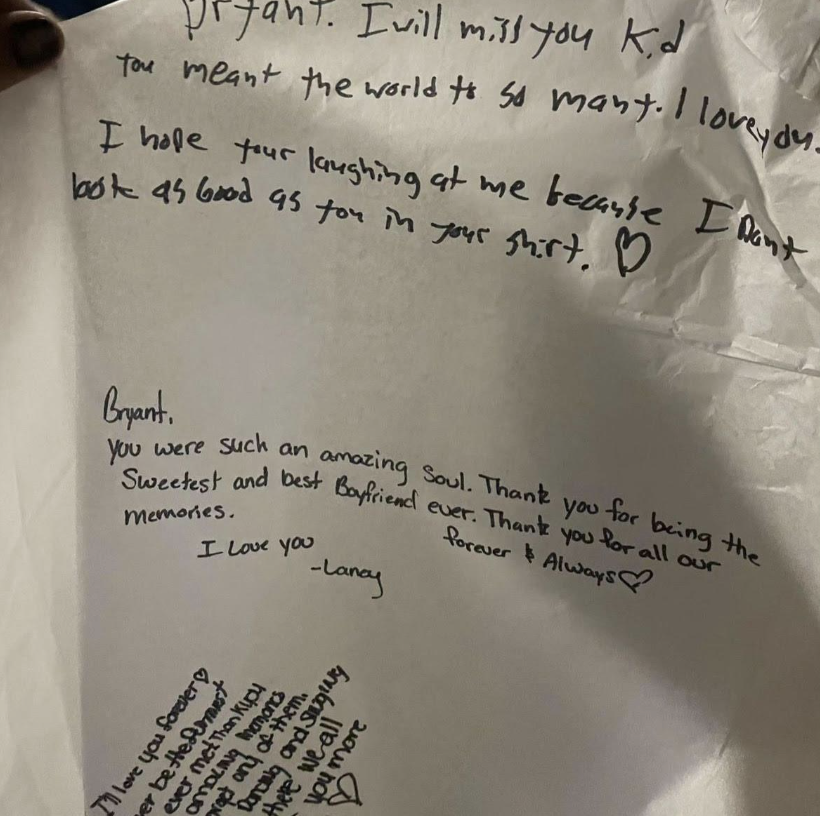

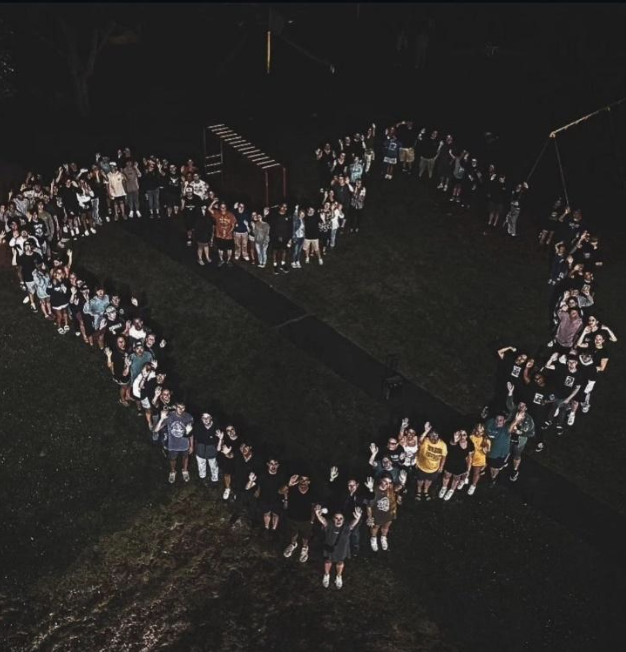

This idea deepened when Bryant Barbush, a classmate from high school, took his own life July 24, 2023. He was a year older than me and was the teaching assistant during my junior year PE class. Naturally, the dynamic prompted my own little hallway crush on him, and so a few brief, flirty conversations kept us connected throughout the semester.

A memorial created by Bryant’s family a month after his passing to be displayed at a local park.

Parting notes for Bryant written on a lantern to be set off during his memorial July 30, 2023.

He asked me to his senior prom at the end of the year, but I already had plans. Nonetheless, he rocked an all-white tux and riled the after-party crowds with his backflips. Our friendship ended there, and I didn’t think much about it until he took his life last summer.

Friends and family gather at a local park July 30, 2023, to celebrate Bryant’s life and mourn his absence together.

The narratives of life and death seemed dichotomous. Life was enjoyed, celebrated, and appreciated; death was grieved, cursed, and terrifying. When life ended, death began, prompting the idea that if you’re struggling in life, you can start over in death.

Bryant’s death reaffirmed this sentiment. As young adults, we imagine death distantly — a far away event that can only be tragic because it’s not meant to be near us. The desire for death among teenagers segregates life and death, and death is used as an escape from life.

When I ended the call with my mom, I still felt uneasy about my patient’s passing. It took another month of volunteer work to realize that his view of death may have been different than mine. I found that the desire for death among the elderly inextricably links life and death in hopes of carrying their life peacefully into death.

After that day, I realized many patients boast the same acceptance; they’re enduring the slow end to their life for the tranquility of death when it chooses to take them.

A sunset paints the skyline near Connecticut Hospice, offering picturesque views to patients.

It’s a weird experience to be surrounded by people who think so kindly of death. It never felt wrong to rejoice in the end of life with elderly patients; in fact, it felt beautiful. Despite my fear of death, I found beauty in its role as the conclusion to a life well-lived — as if death could be a good thing. Still, it’s strange to watch someone experience the kindness of death, and I hope to never become desensitized to its impact despite the few values that it adds to life.

Death has always been the enemy, but given the opportunity to live a full, satisfying life, it seems to be the final knot to a beautifully wrapped gift. It’s not an escape from yourself but rather an augmentation of your whole being — mind, body, and soul.