Criminal justice organization spotlights deaths in state DOC custody

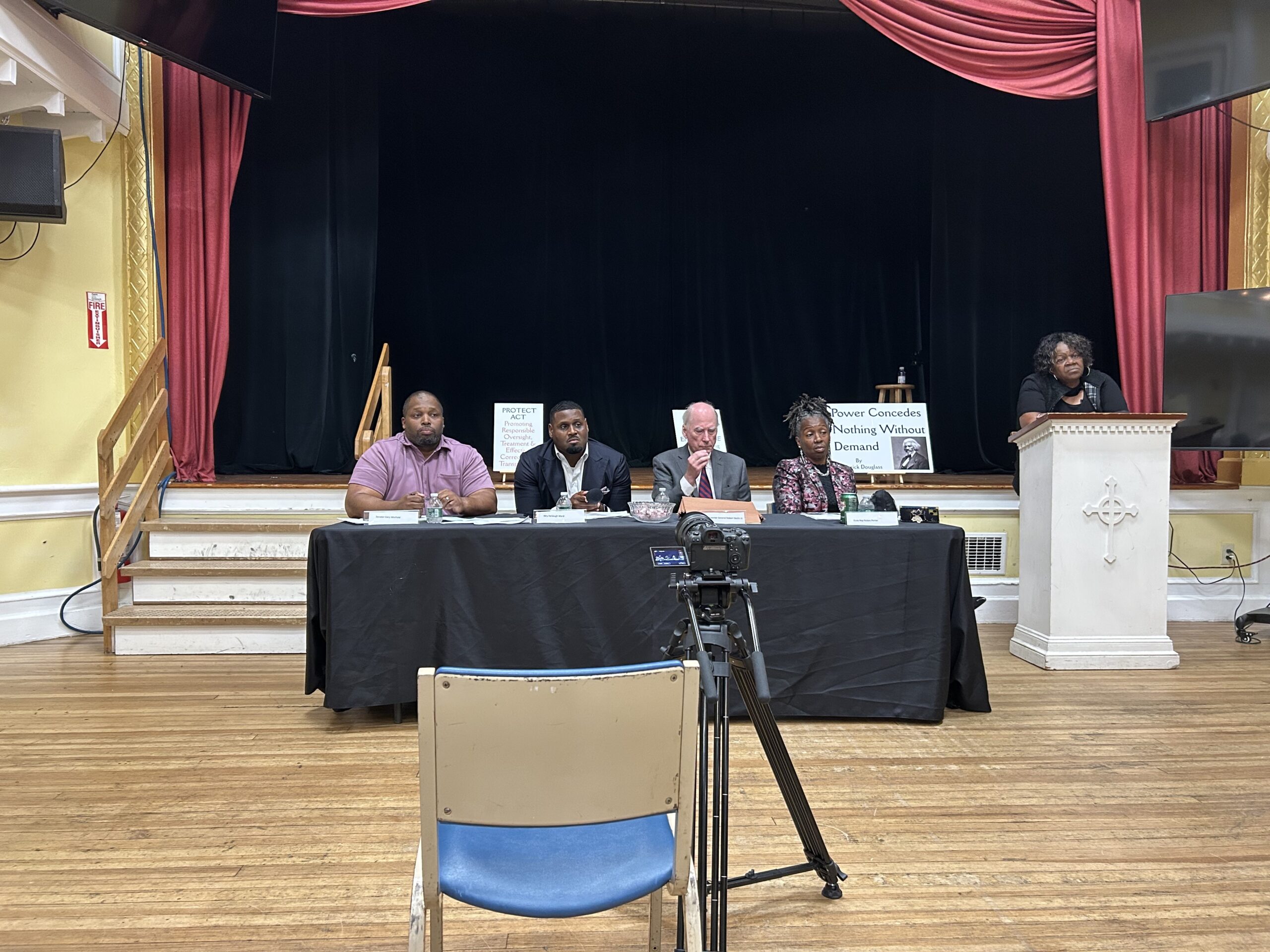

A panel of legislators, the state inspector general and Connecticut’s first independent prison watchdog discussed the deaths of incarcerated people at Stop Solitary CT’s meeting on Friday.

Maia Nehme, Contributing Photographer

Abolitionist Frederick Douglass’ famous remark, “Power Concedes Nothing Without Demand,” served as a backdrop for a criminal justice organization’s meeting about deaths in the state Department of Correction’s custody.

Barbara Fair — an organizer for Stop Solitary CT, which aims to eliminate solitary confinement and improve conditions in prisons — led the meeting on Friday. Fair underscored a lack of accountability for the DOC and urged community members to join in her fight for criminal justice reform.

During the meeting, Fair projected a CT Insider article about J’Allen Jones, an incarcerated man who died at a Newtown, Connecticut, prison in 2018. After Jones refused to comply with a strip search, multiple correctional officers pepper-sprayed him, punched him and forced him onto a bed over a nearly half-hour period, according to a DOC report. The state Office of the Chief Medical Examiner classified Jones’ death as a homicide.

“What is it going to take to make the state of Connecticut accountable for the barbaric things that they do to our people?” Fair asked the meeting attendees with tears in her eyes. “It’s going to take every single one of us to fight. And don’t wait to fight when it’s your child. Fight because it’s anybody’s child … We have got to stop turning a blind eye to what’s going on.”

The DOC did not immediately respond to the News’ request for comment.

The panel featured Inspector General Robert Devlin Jr., attorney DeVaughn Ward — Connecticut’s recently-appointed interim ombudsman, a role that provides independent oversight of the DOC — and state legislators Sen. Gary Winfield and Rep. Robyn Porter, who both represent New Haven. Fair also invited Pablo Correa, a former correctional officer, to speak at the end of the meeting.

Devlin fielded questions from Fair and attendees about his responsibilities as inspector general. Connecticut’s Office of Inspector General, established in 2021, is tasked with prosecuting cases where a law enforcement officer used unjustifiable force or failed to intervene in such an incident.

Devlin said the office focuses on police-involved shooting deaths and deaths in police or DOC custody. The state DOC reported 37 in-custody deaths in 2023, according to the office’s most recent annual report.

Ward emphasized that even if the inspector general’s office ruled that an in-custody death did not involve any criminal offenses, family members of the victim can still file civil lawsuits against the DOC. Before he was appointed as interim ombudsman, Ward secured multiple settlements in legal battles with the DOC on behalf of people who received inadequate medical care in prison.

“Just because the Inspector General’s office says that no criminality occurred does not mean that there was not negligence or malfeasance,” Ward said. “Those are very important distinctions.”

The speakers debated the effectiveness of body cameras worn by correctional officers in deterring violence towards prisoners. Ward said that, across many of the cases he prosecuted, video evidence was often the most transformative in winning settlements.

Devlin mentioned that body cameras are required for police officers, and recordings must be disclosed within 96 hours of receiving a request. Attendees asked panelists why body cameras for correctional officers had not yet been instituted in a similar way. Winfield and Porter responded by describing the political obstacles in the state legislature blocking the path to mandated body cameras.

Fair expressed concern that a mandate requiring correctional officers to wear body cameras would not end up increasing accountability. She noted that, despite an ongoing lawsuit brought by Jones’ family, the footage of Jones’ death had not been released, much less used to hold the correctional officers involved accountable.

“My concern is, even if you’re wearing a camera, who’s going to do anything about it?” Fair asked.

Correa said purchasing body cameras for correctional officers is a “waste of taxpayers’ money,” citing the proliferation of stationary cameras in Connecticut prisons and his concern that officers would turn their body cameras off.

The roughly 30 attendees frequently interjected with personal questions about seeking legal action, based on their own experiences with incarceration or their family members’ experiences. Fair asked attendees several times to save their questions until the end of the meeting.

When the interruptions continued, Fair called for a five-minute break midway through the meeting. Her family then surprised her with two cakes and a rendition of Stevie Wonder’s “Happy Birthday” to celebrate her 76th birthday. Some attendees joined in the song.

Maggie Goodwin, an attendee from West Haven, has witnessed in her time as a social worker how taxing the prison system is on families. She is heavily involved in advocacy, working with Clean Slate Connecticut — a program that erases old and low-level crimes from criminal records — as well as other faith-based social justice groups.

Dyanna Hines attended the meeting to learn more about the systemic issues that lead to racial inequity and unfair treatment of individuals before they even reach the prison system.

When Fair asked Correa why he had worked in the DOC’s “toxic” environment for 22 years, he emphasized his desire to help incarcerated people. Correa said multiple incarcerated people he oversaw in the past still reach out to him for advice.

“If I can change the life of one inmate, and be an inspiration to this one inmate, then I have done my job as a correctional officer,” Correa said. “Our job is not to make their incarceration [harder].”

Friday’s meeting was held in Hamden at 1253 Whitney Ave.

Interested in getting more news about New Haven? Join our newsletter!