Illustration by Davianna Inirio

This piece received first place in the nonfiction category of the 2024 Wallace Prize.

I was on the 212 bus from Lowe’s back to campus; the sun had half-set and from Grand Ave, I saw the silhouette of a strange structure. Three smokestacks towered over the river and cables strung together giant metal columns. As I searched Google Maps and scrolled through the building’s Wikipedia page on the bus, I found out it was an abandoned power plant named English Station. I read that Ball Island was a tiny man-made piece of land in the Mill River between downtown New Haven and Fair Haven. English Station was built on Ball Island between 1924 and 1929 and operational until around 1991, burning coal and oil. It was owned and operated by United Illuminating, which is still the public electric company for the area, until they sold it in 2000.

Having grown up in semi-rural Washington State, I wasn’t used to seeing things like this, the remnants of industrial history. My hometown of Burlington, WA was founded and settled by westerners only about 40 years prior to the construction of English Station. Funnily enough, I’m technically not an official resident of the town because I live in unincorporated Skagit County, making me ineligible to vote for mayor (though I can vote for my fire district chief) or access free public library membership. My valley produces lumber and seeds; we’re most well known for our tulip festival and berry dairy days parade. It’s the kind of place where flocks of swans and geese feed on the leftover crops in the fields in winter and a self-serve corn stand operates on the side of the road–4 for a $1. It’s the kind of place where “I got stuck behind the train” is a valid excuse for any occasion–oil trains can take up to 30 minutes to pass.

In Connecticut, industrial history is easily visible around us. At Yale, in the underground machine shop where I work, I often uncover bits and pieces. I’ve found heavy cast iron bar clamps stamped “Made in CT”; I’ve found glass syringes labeled Becton-Dickenson (a company founded by the father of the Becton that a Yale building is named after) matching a set in the Smithsonian’s American history collection. A vertical milling machine, the basic machine that in conjunction with the lathe, has enabled practically all subtractive metal machining since, is called a Bridgeport as they were invented and manufactured there. These unfamiliar tidbits made me curious about industrial history and infrastructure in this area and its environmental implications.

***

I visited the site of English Station for the first time on a hot September Sunday. On the way to the island, I saw that its soil was held in place by sheets of black corrugated steel rising up from

the river. It took some climbing and crawling and some handiwork with a wrench and pliers, but I was on the other side of a barbed wire fence plastered with “PRIVATE PROPERTY NO TRESPASSING” and “KEEP OUT” signs. An automated voice droned, “You are trespassing on private property. Leave the area immediately. You are trespassing…” It faded behind me until it clicked off when I was out of reach of its camera sensor. I breathed heavily through a respirator. The only other thing I could hear was faint circus-type music from a boxy tan building on the riverbank. I continued toward English Station’s concrete entry archway, feigning confidence. The paved ground was clean compared to the littered roadside in front of the fence. Few people had been here recently.

To the side of the main building were smaller brick structures whose purposes I couldn’t ascertain. I poked through piles of rusted steel, curled and mangled, and peered into the side buildings. The entrances and doors were boarded up and gated, but broken glass said that people or maybe strong winds had gotten in. I brushed through knee-height weeds and grasses to touch vines growing from the poisonous land, up pipes on the brick walls. The branches grew through windows and up to light fixtures, wrapping up wires and pipes. A bright orange sign warning of PCBs was buried in leafy weeds–proof that there was still life in this soil. I read before I came that the site is currently undergoing consideration for environmental remediation because of the asbestos and PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls–chemicals harmful to biological systems) found in the building and water. This process has been going on for several years, but there has been little progress.

***

The second time I visited the site, a laundry basket floated in the river, tied to the bridge with a bright yellow rope. My eyes followed the string up to a man who introduced himself as Michael. He told me that he crabbed here every weekend, usually catching several blue crabs. He didn’t look like any fisherman I’d seen before. My image of fishermen was shaped by friends who went away for the summer to work on fishing boats up to Alaska and by drunk men who came through the McDonald’s drive through where I worked, early in the morning, offering dungeness crabs in exchange for a McMuffin.

I asked Michael whether he was worried about chemicals from the power plant. He said, “Of course, you can tell that the water’s different colors from the morning to the afternoon. There’s definitely some shit in there. But I still crab here and tons of people fish here to feed their

families.” He used to work for a green chemical company in the area where the general rule was that “any chemical is destroyed if you have enough water.” It sounded like the claim of “the ocean’s too big to pollute” from back home.

I proposed we take a look inside and he agreed to come with me. The pathway I had used last time had been blocked off by new sheets of solid steel bolted in place. Michael said that security and barriers–barbed wire fences and padlocks, cameras and alarms–around the site had increased in the past few years. I found another way through, but if that path were blocked, I doubted I would be able to get in again. Not the time to turn back, though. This time, I didn’t give the recorded voice much thought. I still felt highly surveilled; I wore a cute blue dress to try to look innocent if I was caught, but recognized that that wouldn’t work for Michael, who was a tall, broad-shouldered Black man. The cameras were the only things that were new and maintained on this dilapidated site. They weren’t placed surreptitiously–they were bright white and stuck out from walls and poles.

Aside: I do not claim to have made logical, smart choices throughout this adventure. Still, I knew I wanted to do this.

I noticed some things I hadn’t the last time, like lighting bolts engraved in stones that decorated the top of the building. I walked to a back entrance where I remembered that I could get in by loosening a rusted bolt holding a locked fence in place. My hands shaked as I wrangled with my wrenches, but then we were in.

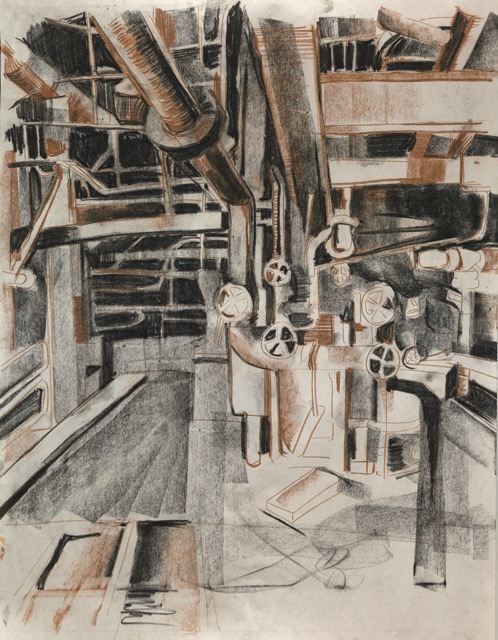

Careful not to step in areas where the floors looked like they could fall through, we made our way through an area with a massive dumpster-like tank with several slots that looked like a larger version of library book return slots. It must have been the main furnace. Delicate sheets of severely rusted metal cracked under my boots, like autumn leaves. Thin layers of grimy liquid in troughs and pools made it unclear whether what I was seeing was real or just a reflection. A bamboo forest of narrow pipes grew from the ground to the pipes above. Sheets of white plastic hung from pipes overhead like moss draped from a tree. Standing beside a giant spool of steel cable, I was a tiny mouse with a spool of sewing thread. I could see massive vertical pipes that probably were too big to wrap my arms around, like giant tree trunks bare of leaves or branches. It brought me back to running through the forest and jumping over the ditch in my elementary school yard or backpacking through the evergreens of the North Cascades–chipmunks left piles of pine cone remnants on tree stumps.

Letters and numbers–some kind of code–were scrawled across concrete and brick in chalky white paint. Diagrams labeled “FLOOD CONTROL” were displayed on walls. One note said, “Caulk electric manholes in August.” Looking up, pipes of all diameters crossed and snaked their way through the limited airspace. Two pairs of chambers–shaped like two sets of lungs–were large enough to fit a small apartment. It felt like the skeleton of a great living being–its bones, fragile and brittle. I could imagine electricity flowing, pumping through the place. Electric currents and impulses travel through bodies, sending messages and regulating heartbeats; electric shocks can kill or bring back life.

I came to an area where the building was open from the ground to the roof. Some parts of the upper floors had been demolished–evidenced by doors in a wall tens of feet above the ground. I adventured up to the second floor, up a set of surprisingly solid stairs with yellow paint flaking off the handrails. Light streamed in through massive windows like stained glass in a cathedral–a sanctum of energy and electricity, a testament to modernity and industry. A crane that could lift 40 tons hung from I-beams above us. Though it wasn’t raining outside, it was in here. I chose to believe it was water. A cylindrical chamber matched another one I’d found outside–I assumed from my limited knowledge of power generation that heated and pressurized fluid was pushed through these to spin turbines to generate electricity. I wish I could’ve seen the turbines as well, but they had been removed in a partial demolition a few years ago.

Up another level, where the floor was only steel grates, it was too dark for my phone’s flashlight to help much. A floor below me, a desk had two drawers still ajar–gloves and papers strewn across the top like someone had left in a hurry. Michael called me over to another room. On the powder blue wall was a grid of switches, colored light bulbs, and tiny TVs: the control room, like something out of a movie. There was a corded phone with no number pad or dial; perhaps its only purpose was to make announcements to the building. It reminded me of the phone we used in the grocery store I worked in to communicate to the other employees and make silly advertisements on donut days and other goofy made-up holidays. A clock was stopped at 20:04:55. I wonder about the people who used to work here. What were their days and nights like?

I thought of my brother, who’s a construction worker back in Washington. He wakes up earlier than I do, even though I live three time zones ahead. He breathes in dust and pours concrete while I listen to lectures and write papers. I think of what my life would’ve been like if I hadn’t come to Yale; I’d probably be a welder or carpenter. But I’ve got weak hands and early-onset arthritis and so I’m here in college (not that I’m unhappy to be here of course; I’m incredibly privileged and lucky).

Michael indicated that we should leave. As I rebolted the gate and climbed back over the fence, I realized I didn’t want to go quite yet. I thought back to something I had noted that I was supposed to look for. I had posted in Facebook groups for Fair Haven history and United Illuminating retirees, asking whether anyone could share memories of English Station. Kevin, who worked there in the 80’s, recalled that “in the front entrance area, there was a large impressive plaque with the names of the guys that worked at the Station who served in WW2. I’m not sure but I think more names were added for the guys that served in Korea.” I didn’t find the plaque.

Outside the fence, while I talked to a couple on the bridge, Michael disappeared.

***

I needed to learn more about power plants. When I went to English Station, I felt like I didn’t know enough to understand how various elements functioned.

Yale Central Power Plant (CPP) stands on the intersection of Grove and York Sts in New Haven, catercorner to Yale Law School, about a 25 minute walk from English Station. Upon approach, it looked fairly similar to English Station–brick foundation with lighter stone accents, arches and towers. The CPP was built just a few years before English, in 1918. But this place is whole, with unbroken window panes and well maintained and manicured lawn and bushes.

Troy, the plant manager and my tour guide, had only been working there for six years, but he rattled off the history of the plant, every upgrade and expansion. He explained that pipes and cables carry electricity, steam, and chilled water to every building on campus (although West Campus and the medical school have their own power plants).

CPP is cleaner and more efficient than English ever was. For example, cogeneration heat recovery steam generators recover heat from the natural gas turbines to make steam and increase the productive output per quantity of gas burned. CPP is also much smaller; it produces up to 16 MW (megawatts, a unit of measurement of bulk electricity), compared to English’s 200 MW (in the 50s, according to Kevin).

The general shapes and silhouettes of CPP’s inner workings were similar to that of English. Endless mazes of pipes were the same, but these were neatly painted and color-coded, not rusted over. There were physical rotary gauges, but also touch screens. The floor was clean, walkways were clearly marked with yellow tape, and fire extinguishers and exit signs were everywhere. A corner contained spare hardware and an array of gaskets neatly organized in blue buckets and racks; also a strange cardboard container labeled “GREEN DUST.” On the 2nd-ish level, what they call level 29 as it’s 29’ above the ground, the view down to the floor level was incredibly reminiscent of that of English, but with more color, especially safety yellow. A shiny orange crane hung from an I-beam on the ceiling, just like in English. Louder here though. On the roof was a beautiful view of campus in its fall colors and a questionable railing constructed of grayed 2x4s, yellow clamps, and blue rope. Cooling towers rose above us.

In the control room, a room filled with computer screens to monitor and command every machine and system, I met Bob. The first thing he said was, “What do you think is the most important machine in this building?”

I tried to be sweet, “You?”

“The coffee machine!,” he responded. That brought me to the reality of the plant’s employees and their work–12 hour shifts, 4 days on, 4 days off, switching days and nights each cycle. Many of them stated that they worked a lot of overtime–one said he worked nearly 90 hours last week. Still, they’ve been happy with how Yale treats and pays them.

CPP was less majestic than English Station. Light didn’t stream into darkness. The enormity of things didn’t overwhelm me. Maybe I didn’t understand its beauty through all its complicated electrical systems. Although it was running in front of my eyes, I couldn’t see the spinning blades and fiery furnaces the way I could imagine in English, where the equipment was cracked open.

Still, CPP let me imagine what English Station might’ve been like back in the day. I imagine that English was grimier and nastier than CPP is now. CPP has fairly stringent environmental regulations to follow; they monitor nitrogen oxide and carbon monoxide emissions. Most of the workers spend their days sitting and monitoring screens and occasionally running checks on the equipment. Automated systems control which systems run and how much they run. It’s a job you want to be boring. There was an array of red emergency stop buttons in the control room.

***

In my research, I found an aerial photograph of New Haven in 1940. At that time, New Haven was a heavily industrialized city–the smokestacks of English Station prominent in the cityscape. Kevin explained that “During WW2 it was running full blast burning coal, feeding the many industries in the area involved in war production. It was guarded by an armed uniformed security force during the war.”

From the Fair Haven history community, most of the comments about the site were about the smell and pollution.

“The smell was horrendous. The water practically glowed green.”

“That place caused folks to develop asthma in Fair Haven! Even the soil in Fair Haven is bad for planting unless you join a community garden or create raised beds.”

“I too remember the green water. You could actually see where the Mill and the Quinnipiac come together. Although the Quinnipiac wasn’t that clean either.”

“We lived close to the river and it smelled bad, then they brought piles of oysters and it was worse.”

“I grew up in Fair Haven in the 60’s and 70’s. The Mill River smelled so bad that we would hold our breaths and run across the bridge near the plant. I can also remember a protest march … where we dumped perfume into the river.”

I also found an insurance map from 1901 that shows that Ball Island and its first power station, called Station B, were already constructed at that point, but the majority of the island was used by L.A. Mansfield Lumber Yard. When I first learned this I thought, “A lumber yard in New Haven?” In my mind, lumber comes from my kind of place (Washington is the second largest lumber producing state after Oregon and my county is among the highest in Washington).

Sawmills and stacks of logs and lumber line streets large and small. When my school district was running low on funding, we started selling timber from district-owned forests. According to my driver’s education (but unverified), Washington is one of the few states where you’re allowed to speed to pass lumber-hauling trucks. But 120 years ago, there was a lumber yard here on Ball Island.

***

While writing this piece, I grew curious about energy sources and power plants back in the area I grew up in. I had long thought that most of our energy came from dams on our valley’s river. Turns out, the majority of the dams on Skagit River are owned by Seattle City Light, making up about a quarter of their energy and contributing to their 88% hydroelectric energy source mix. In contrast, Puget Sound Energy, the private company that provides electricity in my area is only 31% hydroelectric power. I found out that Puget Sound Energy’s largest-capacity natural gas power plant is hidden in the woods just 3 miles from the house I grew up in (practically around the corner in country measures), between a truck testing facility, a lumber yard, and the dump. I guess I knew that there was something there, but it’s pretty well concealed (it’s not even labeled on Google Maps), unlike English Station, which stands strikingly on the Mill River. I passed by English Station once and it begged for my attention; I passed by my home station often and never really questioned it. I don’t know what to make of it.

English Station showed me a piece of New Haven and greater New England’s past–the kind of messy, grimy industrial history I never knew before. English told me a tale of the massive industrial development and the following deindustrialization the U.S. went through as part of becoming the nation it is today. She showed me beauty and life in electricity and machinery, along with the dirty reality of environmental and health issues that go with it. But she also reminded me of home and made me question the way things are there too.

I don’t know what the future of English Station should be, and I don’t think I should have any say in it. Let’s just say I’m just an outsider who likes rummaging through places I shouldn’t be.