Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you’re aware that abortion has become a highly salient issue since Roe v. Wade was overturned in 2022. The backlash to the Dobbs ruling was, in my view, the key reason why Democrats overperformed expectations in the midterms; if you look at the data, Democrats were running behind Biden’s 2020 margin in special elections until that case was decided, at which point they started overperforming. And pro-choice ballot referenda have passed in every state that has had them since Dobbs, including those like Kentucky, Montana and Ohio that Trump handily won twice.

Given the seeming strength of abortion rights at the ballot box, should Biden make them a central issue for the presidential race? The other week, I was discussing that question with one of my professors from last semester, and he pointed me toward a pre-print paper by Natalie Hernandez GRD ’26, a fourth-year political science doctoral candidate, titled “American Public Opinion on Abortion is Less Polarized than Pro-Life and Pro-Choice Labels Suggest: Evidence from Two Surveys.”

After reading the paper, I spoke with Hernandez about it. The key takeaway of the paper is that traditional survey questions fail to capture the nuance of public opinion on abortion. “In the news what we hear is that the U.S. is so polarized about abortion,” she told me. “When you look at the data, most Americans fall into the middle.”

Gallup and Pew polls, for example, give voters a binary: pro-life or pro-choice. The American National Election Survey gives voters four options: always permitted; permitted, with some exceptions; only permitted for limited exceptions; or never permitted. This can make public opinion on the subject seem more polarized than it really is, Hernandez said. “When people are forced between two extreme options, they pick the closest one to their views, even if it’s not a perfect match.”

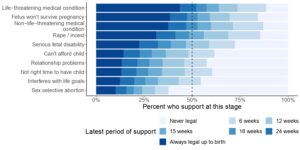

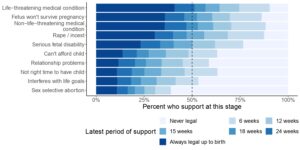

Hernandez ran two nationally-representative surveys (n=32,245), giving people 10 different scenarios in which a woman might need an abortion, and asking respondents up to how many weeks — if at all — they think abortion should be legally permitted for each of them.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, only 15 percent of respondents were what Hernandez called ‘polarized consistent’: that is, they support either legally permitted abortion up to birth or a no-exceptions ban for all ten scenarios. (This group split down the middle between those two extremes.) Another 4 percent of respondents were ‘non-polarized consistent,’ picking the same period for legality other than the two most extreme choices throughout all scenarios (e.g., for all ten reasons consistently picked 15 weeks). The vast majority — 81 percent — were what she calls ‘abortion situationalists’: people who “update up to what point in a pregnancy they think abortion should be legal in accordance with the reason given.”

Overall, the median voter favored legal abortion up to 24 weeks for cases where the life of the mother was at risk; up to 18 weeks for cases where the fetus would not survive pregnancy or the mother had a non-life-threatening medical condition; up to 15 weeks for cases of rape or incest; 12 weeks for cases of serious fetal disability; and up to six weeks for situations where the mother was not ready to have a child, due to timing, relationship issues, financial reasons or interference with her life goals (the most common reasons women seek abortion). The median response was that sex-selective abortion should never be legal.

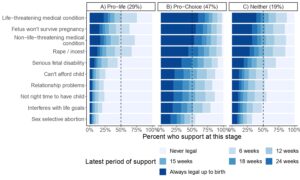

“The median pro-life voter,” Hernandez noted, “supports legal abortion up to six weeks for cases where the life of the mother was at risk, the fetus won’t survive pregnancy, non-life threatening medical conditions, and rape. ” And among pro-choice respondents (47 percent of the sample), almost half thought that sex-selective abortion should never be legal. “There is more variation in pro-life and pro-choice identified respondents than you may expect.”

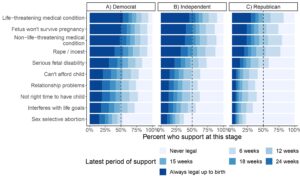

Although her survey found that partisan identity was correlated with pro-choice or pro-life identification, respondents’ views were much more similar when given specific scenarios. Although a majority (53 percent) of Republicans identified as pro-life, the median Republican favored legal abortion in half of the 10 scenarios in Hernandez’s second, larger sample. And while 70 percent of Democrats identified as pro-choice, the median Democrat favored some time restrictions in seven out of the 10 scenarios.

I asked Hernandez how her results squared with the recent winning streak of pro-choice ballot referenda, including in red states. Why aren’t people in right-of-center electorates voting down ballot measures that don’t include the limitations your data says they prefer? “There is a difference between what the masses want and what elites are offering,” she said. “Maybe when people are forced between two extreme options, they pick the closest one to themselves.”

This fall, Florida and Arizona might provide a useful pair of bellwethers to test her theory. Recently, the Florida Supreme Court made two important decisions: first, it ruled that a six-week abortion ban signed by Gov. Ron DeSantis ’01 could go into effect; second, it cleared an initiative to amend Florida’s constitution to allow abortion up to the point of fetal viability, typically 24 weeks, for the November ballot. On April 9, the Arizona Supreme Court ruled that an 1864 abortion ban could go into effect; an abortion rights initiative is likely to appear on the ballot in the fall.

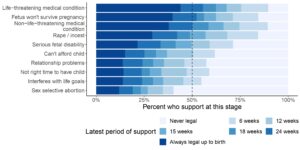

Arizona

Florida

Hernandez’s survey had a large enough sample size to pull out the Florida and Arizona subgroups. As you can see, the median Floridian and Arizonan appears supportive of legal abortion closer to viability in certain scenarios such as the mother’s health or rape and incest but would favor the current law in cases where the woman can’t afford the child or is having relationship problems. And under the Florida state constitution, referendums need 60 percent of the vote to pass. Based on Hernandez’s findings, pro-choice campaigners would do well to focus their messaging on the more sympathetic scenarios. “It is likely that pro-choice and pro-life identified respondents have different ‘typical abortion scenarios’ in mind,” Hernandez writes in her paper. The more that advocates can focus their paid and earned media efforts on the cases that the data finds the broadest support for, the more likely they are to secure a progressive win in two right-of-center states.

MILAN SINGH is a sophomore in Pierson College. His column, “All politics is national,” runs fortnightly. Contact him at milan.singh@yale.edu.