Adam McPhail, Contributing Photographer

On Tuesday, March 26, the Peabody Museum, which had been closed since early 2020 due to renovations, reopened its doors to the public.

The News was one of the first visitors to the Peabody’s new exhibits, which feature 2,215 of the 14 million specimens in its collection. The News walks through highlights here.

Main entrance and first floor

Upon walking through the main entrance, guests first encounter a family of four Pteranodon sternbergi. The male flying reptile dinosaur — with an almost 20-foot wingspan — is displayed, wings outstretched, above the information desk. The female fossil climbs along the wall, and two baby Pteranodon sternbergi perch on a neighboring ledge. Like many of the Peabody’s renovations, guests can view this fossil exhibit up close from the second floor.

After stepping through the front door, visitors enter the Burke Hall of Dinosaurs.

The unmistakable centerpiece is the towering 75-foot-long Brontosaurus, which hangs from the ceiling in its totality.

As opposed to its former display in the Peabody, the Brontosaurus is now arranged slightly differently than before, reflecting recent scientific discoveries. One of the most notable corrections is its lifted tail. Previously, paleontologists thought that Brontosauruses dragged their tails on the ground.

“When ours was [originally] mounted, it had an unusual kink in it with the tail going down,” Susan Butts, the director of collections and research at the Peabody, told the News. “Biomechanically, the bones don’t move like that.”

The fossil also includes 27 additional vertebrae and ventral ribs based on additional discoveries. Curators also remounted the Brontosaurus’ head to be more proportional to the rest of the body.

The Stegosaurus, with its characteristic kite-shaped plates on its back, is another one of the Hall’s highlights.

Like the Brontosaurus — and many other exhibits in the Peabody — the new Stegosaurus display more accurately depicts the species, Butts said. The exhibit was corrected based on an undergraduate’s senior thesis, which identified previous errors. Following the research, the Peabody resized the dinosaur’s legs to be more proportional to its body, decreased the number of tail spikes from eight to four, and rearranged the back plates, Butts said.

Along the upper wall of the Hall, “The Age of Reptiles” mural serves as an artistic timeline of life on Earth. Painted by Rudolph F. Zallinger ’42 ART ’71 in 1947 as a fresco for the Peabody, the 110-foot painting captures Earth from the Late Devonian to the Cretaceous period. Butts noted that the mural reflects the scientific knowledge of life during the 1940s, meaning the Brontosaurus in the painting still has a dragging tail.

However, visitors don’t interact with only land-based dinosaurs. They are also introduced to the Ancient Ocean in the Hall, where a collection of extinct sea creatures brings to life the world from over 500 years ago. Now, 160 invertebrates are on display, compared to the 26 that were up before the renovations.

According to Butts, the new exhibits highlight some of the most famous pieces in the Peabody’s collections, including sea scorpions, trilobites — marine arthropods that “conquered prehistoric oceans” — and mollusk-like ammonites.

As visitors walk through the first floor, history unfolds from life in the Ancient Ocean to human evolution.

“The World of Change”

66 million years ago, an asteroid hit the Earth, causing over 75 percent of plants and animals to go extinct. The climate and life on the planet were dramatically transformed.

The “World of Change” gallery captures the new life forms that thrived on the planet in its new warm greenhouse environment. The exhibit focuses on the last surviving dinosaurs, birds and mammals following the mass extinction.

The center of the room features a fossil of a Megacerops, a herbivorous mammal that flourished during this time. Other fossils of herbivores and their adaptive features — including strong and flat molars that could chew through fibrous plants — show Earth as it was 66 million years ago.

Over time, the Earth began to cool down. By 23 million years ago, the planet became an Icehouse. The following exhibits in the Peabody highlight new lifeforms that thrived in the cooler environment, which eventually gave way to grasslands and hominins — including the human species.

The human footprint

The Peabody has a new exhibition dedicated to human evolution. Along with panels detailing the impact human evolution has had on the planet, it also features a timeline of human evolution, beginning eight million years ago, when the common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees first appeared.

“The curator made this as a braided stream,” Butts said. “One of the things that’s really interesting about humans now is that we’re the only species. That’s rare.”

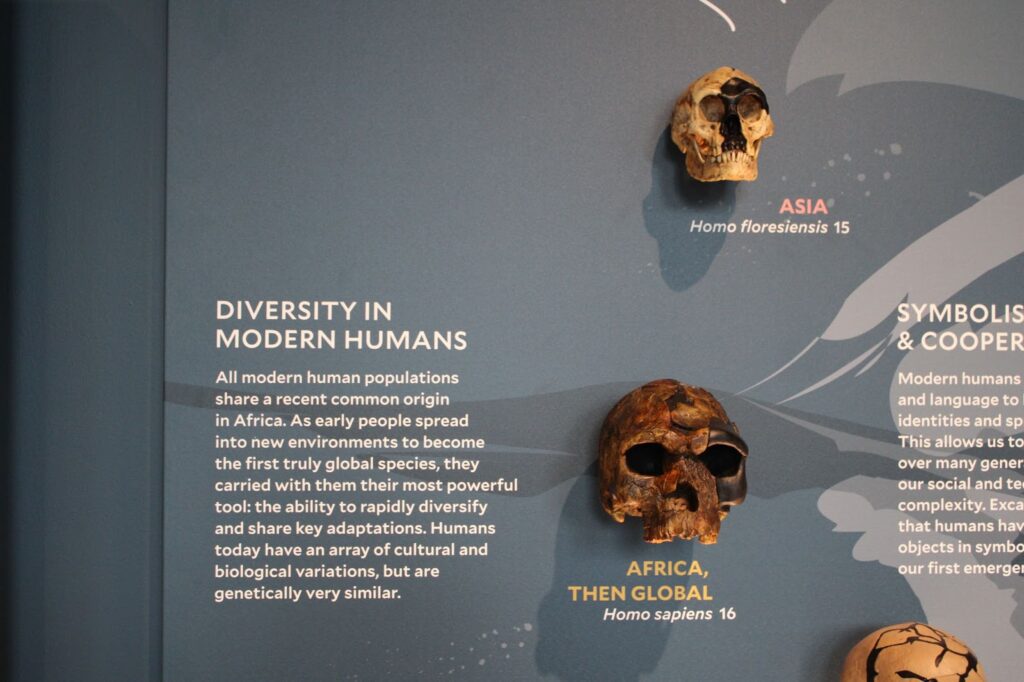

The exhibits attempt to describe the flow of evolution and the different migratory patterns of evolving human ancestors, with Africa at its center. On one panel, visitors can see various bronze-cast skulls, which represent different human species, each of which has its own distinctive adaptive features, such as brain size.

The gallery’s selections also outline how human existence has impacted the Earth. The Peabody shows how research on its collections has shown the impact of human life on animals, plants and other resources.

For Gonzalo Giribet, the director and curator of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University, these vast collections are one of the strengths of university museums, especially when tracking the impact of climate change.

“We are doing genetic studies on specimens that were collected 10, 50 and 100 years ago, so we see how the genomes of these organisms have changed through time,” Giribet said. “We can see how they respond to climatic variables, population changes or respond to invasive species.”

The rest of the gallery exhibits different animals that once populated the Earth, including land giants, such as the wooly mammoth.

Second floor

The Peabody’s second floor features human culture galleries, including exhibits on the History of Science and Technology, Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia and Mesoamerican and Andean civilizations.

The History of Science and Technology exhibit also describes Yale’s history with science, research and technology. The Sheffield Scientific School at Yale, which was open from 1847 to 1956, helped develop numerous notable scientists and inventors.

The exhibit also includes labels that explain the school was partially funded by seized Indigenous lands and profits accrued from slavery-associated activities.

“Eternal Cities” is a structural artwork created by Mohamad Hafez, a Syrian-American artist and architect, who also owns the Pistachio Cafes. The piece, which is a collaboration between Hafez and the Peabody, attempts to represent the millennia of cultures that have shaped Damascus and other cities in the Middle East.

The artwork includes 3D prints of the Babylonian Collection, found on the neighboring wall of “Eternal Cities.”

“This piece is meant to evoke Damascus or another Middle Eastern city and the millennia of cultures that have existed in this place,” Kailen Rogers, the associate director of exhibitions at the Peabody, told the News. “There’s a nod to the contemporary destruction and loss of culture in the area. There’s also a lot of hope. There are plants, laundry and a lot of glittery gold.”

Beyond the Babylonian collection, the second floor also holds many artifacts from Ancient Egypt and Mesoamerican and Andean civilizations. Some of the pieces in these exhibits, Rogers said, are on loan from the Yale University Art Gallery.

Only the first two floors are currently open to visitors. The Peabody will open the third floor to visitors at an undetermined date in the future.

Though it was previously free to only Yale students and faculty, the Peabody now offers free admission to the general public.