When I was speaking with my father over winter break, the age-old debate around French military service came up. “I did it, your uncle did it, your grandfather did it. So why shouldn’t you?”

My father, much like many French policymakers, strongly believes in bringing back mandatory service. Under President Emmanuel Macron’s new rules, French youth over 16 years old will have the opportunity to serve for a month, but policymakers are also considering bringing back the old mandate for military service, where every French citizen would be required to serve for a minimum of 6 months. Ostensibly the “Service National Universel” aims to transmit French republican values and maintain national cohesion, but its return is of course tied to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — and a possible second Trump presidency.

The election is still six months away, but at the time of writing, Donald Trump looks like the favorite. “Gun to my head, I’d give him between a three-in-five and two-in-three chance of winning the Electoral College, pricing in polling, legal issues, abortion, and everything else,” says Milan Singh ’26, who is an opinion columnist for the News.

Trump has repeatedly stated that he would end American aid to Ukraine. From stating that he would let Russia do “whatever the hell they want” to NATO allies that don’t meet their financial goals in the alliances, to blatantly answering “yeah” when asked whether he would not defend NATO countries, it’s clear the alliance is in peril.

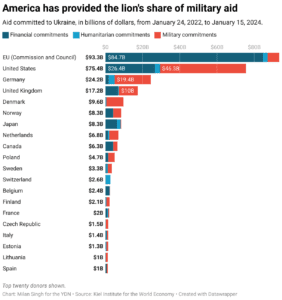

The United States is currently the largest contributor of both military and humanitarian aid to Ukraine by far. If this aid were cut off, Europe would be faced with some very tough decisions.

In anticipation of a possible second Trump administration, European leaders have begun discussing plans for a world without American support. Macron has renewed his calls for France to reinstate mandatory military service and for Europe to embrace a doctrine of “strategic autonomy” — that is, to maintain a large enough defense force to abstain from American assistance.

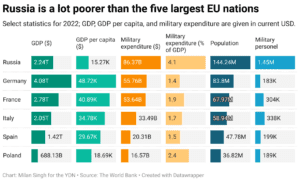

Europe is already inching in that direction. Germany, the Netherlands, Spain and Romania have bought 1,000 Patriot missiles, systems that are able to eliminate airborne threats, while Denmark is sending nearly all of its artillery to Ukraine. But the fact remains that the United States has provided the lion’s share of military aid, and right now, Europe simply does not have the capacity to fill the gap should Washington turn isolationist.

All of this comes as the Ukrainian counter-offensive has stalled in the face of legions of Russian conscripts. Although the Ukrainians have access to important anti-armor and anti-air weapons systems as well as artillery capabilities like CAESAR and M109 systems, which are used for long range bombardment, they simply don’t have enough munitions and personnel to sustain the war at its current pace. Fortunately, Europe does have the financial firepower to fill in for an absent America. But, if Europe does not rapidly increase defense spending, military aid, and pivot to war time economies, the situation for Ukraine looks rather bleak.

At present, it’s not clear that Putin would stop at Kyiv. During his tenure as president, he has launched military interventions in several nations: Mali, via Wagner PMC; during the Syrian civil war on the side of Assad; in Georgia; and in Crimea in 2014. If Trump follows through on his promise to kneecap NATO and Ukraine falls, Putin would only be emboldened.

Today it’s Ukraine, and tomorrow it might be the Baltic States and Moldova. Top officials in some of these countries are already sounding the alarm. The German defense minister publicly worries that Putin might attack a NATO country within the next five to eight years.

That is not to say that further Russian invasions are imminent or even likely. Still, Europe must prepare itself for a world where America takes a diminished role in defending it from Russian aggression. The fact of the matter is that Europe has the money to support Ukraine’s defense and its own. Whether or not Trump wins, it is in the continent’s interests to pursue strategic autonomy. What remains to be seen is whether there is the political will to do so. Although Europe has the necessary endowments to achieve strategic autonomy and guarantee the safety of the continent, policymakers and citizens alike are still reluctant to prepare for a world without American assistance. Whether we see this depends on both Brussels these coming years — and in America this November.

LUCA GIRODON is a sophomore in Branford College. Contact him at luca.girodon@yale.edu.