PROFILE: Haejin Park explores childhood memories and womanhood through watercolor

Having worked as an editorial illustrator for publications such as the New York Times and VICE News, Park is a current MFA student at the Yale School of Art who creates vivid dreamscapes through her watercolor paintings.

Courtesy of Pat Garcia ART'24

When Haejin Park ART ’25 wants to access her memories, she travels to the “mind palace” of her grandmother’s home. The past appears in images that flicker across on a TV screen –– what Park calls “memory video.”

Since then, the theme of memory has been recurrent in her strikingly vibrant watercolors. The News sat down with Park to discuss her upbringing, recent works and goals as an artist. Before coming to the School of Art, Park had worked extensively as an editorial illustrator, creating watercolor illustrations for the New York Times and Vice News. Now, as a first-year master’s student, Park said she hopes to renegotiate the terms of memory, seeking to remember moments of personal trauma and excavate moments of the past –– even those that no longer exist. In particular, Park remembers Munhwa-dong, a village where she lived with her grandparents until age five.

“This mind palace is where I’m from,” Park said. “Now, that village is gone. Like the whole village is gone. It’s getting redeveloped, where most of the land will become apartments. I don’t have a photo of it. My mom went there, and she also decided to not take a photo of it because it wasn’t what we remember. But it stays in my memory, in a mind palace.”

“Mom don’t leave”

Park recalled her childhood growing up in what she described as a poor, rural neighborhood in Cheonan, a city 50 miles south of Seoul. To seek better economic prospects, both of Park’s parents worked in Seoul –– traveling for an hour and a half from their home. While they worked and lived in the city during the weekdays, Park stayed at her grandparents’ house who looked after her.

At times, Park was separated from her parents for at least seven, and sometimes up to 14 days. The memory of her parents saying goodbye and leaving for work at the end of every weekend has lingered as a form of trauma for Park, she said.

“The scene that I’m telling you is like, I’m in the doorway and she’s leaving. She’s saying ‘Bye, I’ll be back.’” said Park. “My dad has already left, he leaves first and he’s a couple steps away from the door.”

Recently showcased in the Yale School of Art’s first-year thesis exhibition, Park’s work “엄마 가지마 (Mom Don’t Go)” depicts this memory of her mother’s departure through a multi-faceted installation that involves a water-color painting, painted blue tapes, a pedestal and a door.

A thin string is tied to the handle of the door and draws out to the surface a white rectangle — which, according to Park, is supposed to invoke the imagery of an outstretched arm. Whenever someone enters or leaves through the door, the string is pulled out of the hole on the rectangular pedestal and drags across the floor.

Caption: “엄마 가지마” (Mom Don’t Go).” Watercolor on paper, door, pedestal, painted blue tapes / Courtesy of Pat Garcia ART ’24.

When Park turned five years old, her family, along with her newly-born brother, finally reunited and collectively moved to Seoul.

“Teddy Bear Hospitals: Season 6, Episode 1”

Park, as well as her family, is no stranger to goodbyes. Throughout her early childhood and adolescence, Park’s family moved more than 20 times. At the heart of these relocations was money: the family moved when they did not have enough money or when they suddenly had more.

Then, when Park was 15, she moved across the Pacific Ocean, with her mother and brother, to Los Angeles. There, she confronted the difficulties of adjusting to an American school system, while facing interruptions in her education due to visa-related issues.

On the eve of her senior prom, after recently being accepted into Rhode Island School of Design, Park experienced a psychotic break, she said. She said the exact cause of the breakdown is still unknown. Perhaps it was the rift with her best friend, high levels of stress running in her family or the huge shifts caused by the move to America, she said.

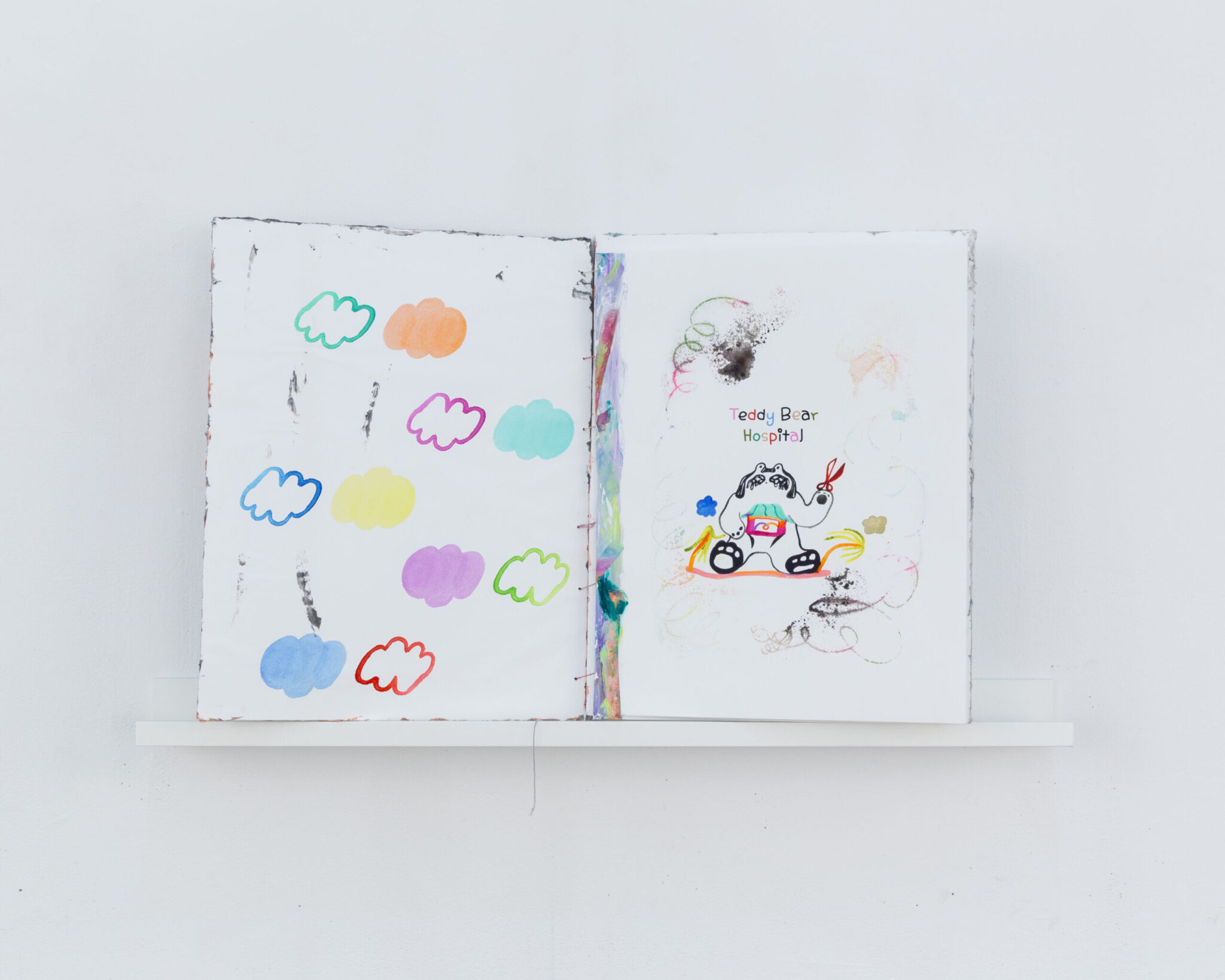

Regardless of the cause, the memories of this psychotic breakdown have prominently influenced and motivated Park’s work. In particular, the three weeks following the incident have served as the backdrop to her book, which was also displayed at the thesis exhibition, “Teddy Bear Hospitals, Season 6, Episode 1.”

“I found myself returning to the memories in mental illness, in what happened during that three weeks of intense breakdown,” Park said. “The book is about what happened on the first day. That’s when I, again, separated with my mom, because I’m in the hospital, and my mom is at home. And I’m here, but she can only visit me for like an hour, and she has to leave.”

Caption: Book with the cover of “Teddy Bear Hospital”. Watercolor on paper, string, painted blue tapes / Courtesy of Pat Garcia ART ’24.

Cute and spooky: Haejin’s colorful world

When there were no children’s books at her grandparents’ house or when high-schooler Park was still learning to adjust to the English language, she turned to color. However, Park’s relationship with hues and shades is a bit more complicated than that of other artists.

Park said that her therapist had diagnosed her with synesthesia: a perceptual phenomenon that causes sensory crossovers, according to Cleveland Clinic. In some instances, people with synesthesia see shapes when smelling certain scents or perceive tastes when looking at words. In Park’s case, she can see colors at the thought of certain individuals and memories.

As a person walked past during the interview, Park said that the person emanated a pale shade of blue.

“For me, color is a mother,” said Park. “We all drink water and we produce color. I am a watercolor, on paper. I draw with my tears. I drink water, I paint with water, I make blood when I make period art. And I am told always that this is never enough because I’m not painting on oil on canvas.”

It is not merely incidental that Park describes color in gendered terms. While Park’s work centers around memories and events that are specific to her personal history, she aims to tell a much larger story about, and for, Korean women.

Park addressed the intergenerational struggles of Korean women. In particular, she pointed to the internalization of misogyny, the Korean War’s legacy of mental illness among women and the invisibility and silencing of Korean women throughout history.

“I asked my mother, ‘Why didn’t you like me more than my brother?’ or ‘Why did my grandmother cry when I was born?’” Park said. “When I asked her why, she said that it’s because her mother also favored her brothers over her. There was a lot of mental illness because of the war. I also studied East Asian art history last semester [and] I learned about what it meant to be a Korean woman when there is no record. That made me think about motherhood, in the sense of mother country or mother language.”

Even though Park’s art carries weighty ghosts, her work is marked by vibrant drips of pink and orange, images of smiling faces hidden in flowers and huge “anime-inspired” eyes that return the viewer’s curious gaze. These jubilant and almost youthful elements may seem jarring to the viewer, considering the darker source material that has inspired the piece.

Yet, the simultaneity of cuteness and spookiness is one that Park associates with the experiences of being a Korean woman in America.

“(The anime-inspired eyes) are not just cute,” Park said. “It’s cute but a little scary. There’s something behind the eyes. There are a lot of scary, spooky things that happened in real life to me, that didn’t happen to other people.”

Caption: The back and front cover of“Teddy Bear Hospital”. Watercolor on paper, string, painted blue tapes / Courtesy of Pat Garcia ART ’24.

For Taína Cruz ART ’25, the merit of Park’s work comes from this very complexity and mystery. According to Cruz, she has found excitement in uncovering the multiple layers of Park’s work, which she does not always fully understand or know how it was created. The complexity of Park’s work is especially apparent in her use of color, said Cruz.

“It’s just really wonderful how Haejin is using color and the vibrancy to display womanhood, to display emotions, to display aboutness, our beings and what it means to be just like consciously alive in this world,” said Cruz. “Haejin has really found a wonderful language to communicate all these questions that we’re pondering ourselves, in a way that is fun. And as someone who is just constantly seeking out play, I have fun playing and exploring within Haejin’s work.”

According to Ryan Brooks, Park’s partner, her current work centers her identity and emotions, in ways her past commissioned pieces did not. Incorporating her personal narrative in her art has been the key to “unlocking so much growth,” said Brooks.

Park noted the intense emotional attachment she feels for her works. Following the performance of the door opening in “Mom don’t go,” she said she “could not stop crying.”

“Her work is about this relationship with color to paper,” said Brooks. “A lot of her work, I think, is using these mediums to talk about her experience, both externally as a Korean woman and internally in processing complex trauma. This process is almost like a gradual uncovering, if you will. By exploring more into the work, she can use this process as a way to unpack things that have maybe been packed away in her memory.”

Considering the many times Park has moved around and begun anew, it may come as no surprise that Park envisions herself taking on new challenges around the world.

Particularly, she said, she wants to attend the Venice Biennale — an annual international cultural exhibition — 10 years from now.

“I would invite all my family from Korea and show Italy to them and eat tomato spaghetti with some red pepper flakes on top and strawberry wine with the bubble water,” Park said. “Probably feeling happy but planning what’s next.”

In 2021, Haejin was selected as a finalist in the Bologna Children’s Book Fair.