Thisbe Wu

Growing up in rural West Texas, Christian Wiman didn’t have much of a reason to question the faith for which he was named. “The roots were pretty shallow where I grew up,” he told me when we met on the quad of Yale Divinity School (YDS). Appropriately, we were seated under an oak. Trees—a feature his childhood landscape lacked—are among the most prevalent motifs in his ten books of prose and poetry, pointing toward a desire for the rootedness that might arise from a more reasoned, resilient faith than the one he grew up with. But this is not to say that he scorns what he calls the shallow-rooted “easy devotion” of his elders, for whom Christianity was as much a given as cactus or killdeer. At times, he envies it. When I asked Wiman what trees meant to him, he replied, a bit wistfully, “Peace”—a quality that no doubt defined his relatives’ pious lives more than it does his own.

Wiman’s lack of peace, professionally speaking, is something many poets would covet. Since his first book of poems, The Long Home, was published to acclaim in 1998, he has received honors for almost every new book. Between 2003 and 2013, he also served as editor of Poetry, the oldest monthly of new verse in the Anglophone world. Since he left that position, he has not only produced two poetry collections, but also become a professor at YDS, where he teaches courses including “Poetry and Faith,” whose popularity has spread down Prospect Street to spiritually inclined undergrads. As YDS Dean Greg Sterling put it to me in an email, Wiman is not only “one of the most significant figures in religion and literature today,” but also “a Yale treasure.”

Yet anyone who knows Wiman’s work knows that his literary success belies decades of instability in his personal life. As an undergraduate at Washington and Lee University, Wiman disavowed his Christian faith, a process he traces to reading Nietzsche and making his first secular friends. Today, he views this change less as a loss of faith than a fanatical transfer of faith into literature. A mentor at Washington and Lee told him that an aspiring poet ought to travel rather than get a Master of Fine Arts degree. After college, he took the advice to heart, moving forty times in a span of fifteen years. At first, it seemed to work: “moving to a new place would really jolt me,” he said, granting him what he ironically described, in a 1998 essay called “Milton in Guatemala,” as “a store of EXPERIENCE.” (“To this day,” he wrote of Paradise Lost, “I can’t open the poem without catching some quick whiff of strong coffee, avocados, and black beans.”) Wiman’s itinerant lifestyle and single-minded devotion to poetry strained his relationships. The faith he had then, he told me, “was mostly faith in poetry,” allowing little room for investment in his relationships with people, let alone God.

In retrospect, such smaller struggles might together seem a prelude to a single, greater struggle. In 2005, three weeks before he planned to resign from his job at Poetry and move to Tennessee with his wife, the poet Danielle Chapman, he was diagnosed with a rare form of cancer that would uproot his life and force him to face death again and again. It was his thirty-ninth birthday. Coming just a year after he and Danielle fell in love, the diagnosis awakened him, as he describes in My Bright Abyss, to “an excess of meaning for which I had no context.” The pain he felt was a sense not of meaninglessness, but of “the world burning to be itself beyond my ruined eyes.” And so, in keeping with a theme that defines his work—love felt most acutely in loss—he returned, however improbably, to the faith he had already begun to feign in the “awkward and self-conscious” prayers he and Danielle liked to say before dinner. His unbelief began to seem like unacknowledged belief; where he had previously seen only absence, he began to see presence. God was a presence that existed not in spite of or instead of absence, but in it. Years passed before he would give that presence a name.

Wiman’s originality as a poet and thinker lies partly in his refusal to distill his experience of faith into a linear progression with a decisive conclusion. Although Dean Sterling rightly called My Bright Abyss “the most important story of conversion since C. S. Lewis’s Surprised by Joy,” Wiman’s is not a classic conversion story. He is confident that his struggles against faith, whether precipitated by his own mind or by the state of the world, will never leave him. “I think any honest, conscious person in today’s culture can’t possibly claim some sort of strong faith,” he told me. “Easy devotion” is an artifact of his childhood; in its place stands a variable faith he is committed to reproducing in language. In “Prologue,” the first poem in his 2020 collection Survival Is a Style, he sets himself this task, writing, “I need a space for unbelief to breathe.” Wiman has carved out that space in American poetry.

*

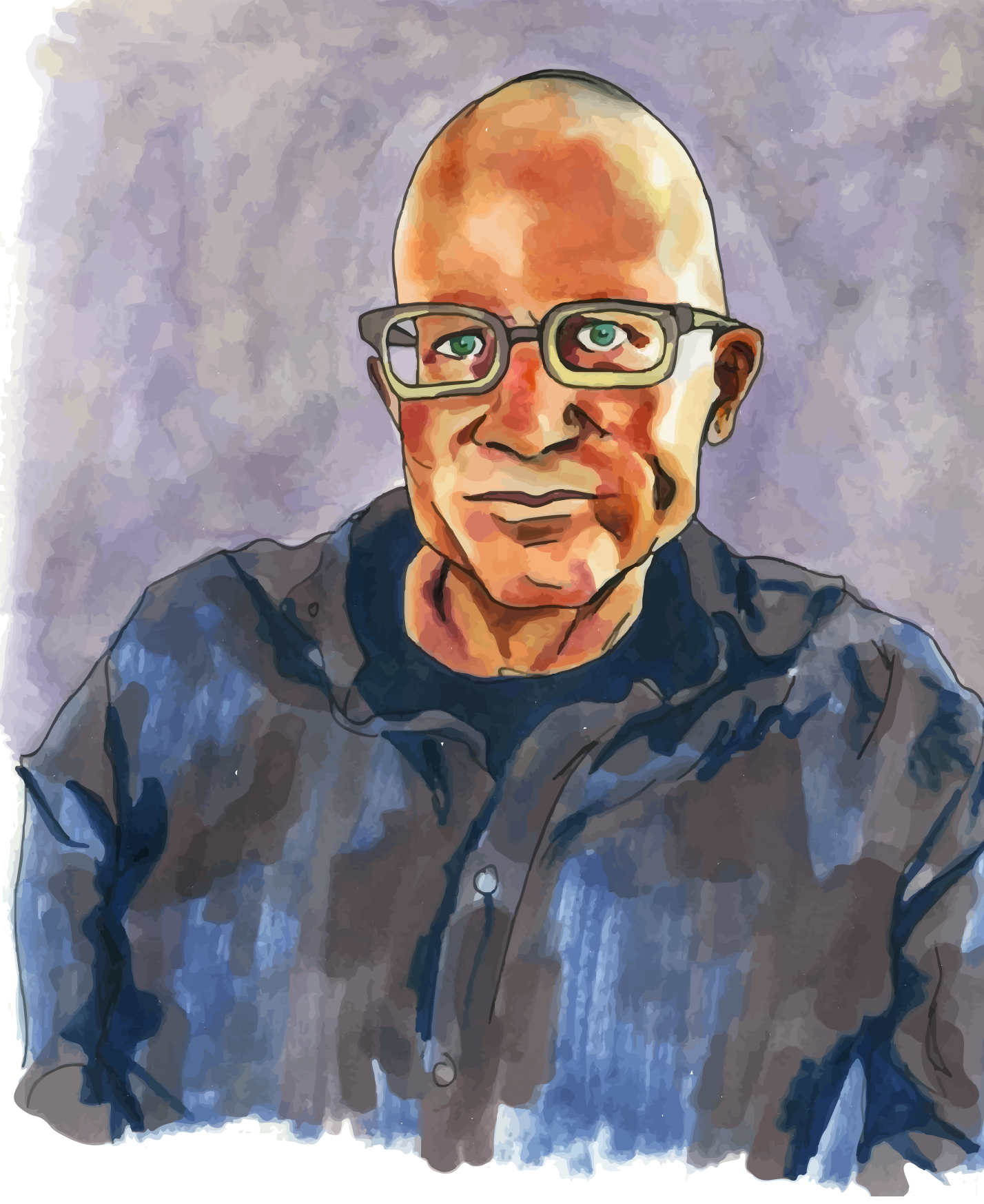

“My early poems are horrible,” Wiman told me, when I asked him how he’d grown as a poet. Compact and slightly delicate, with a soft-spoken Texan twang and blue eyes whose tiny pupils always seemed to look past me—or maybe through me?—Wiman is funniest when he is self-deprecating, both in person and on the page. Like most poets I’ve encountered, he is naturally serious, but he is quicker than most to poke fun at that seriousness. In Survival Is a Style, he has a poem called “Ah, Ego” in which he calls the subject “my beetle,” “my cockroach,” and “moon rover roving over / the moon of me.” Such self-scolding is likely part of his appeal to secular readers, imbuing even his most pious poems with a conspiratorial intimacy.

But Wiman wasn’t always so self-effacing. The poems of his hardscrabble youth are marred by self-seriousness that often veers into sentimentality. In a poem from The Long Home called “Clearing,” for instance, the speaker experiences a moment of serenity in a forest, only to editorialize it with an artist’s self-consciousness—“you could believe / … / a man could suddenly want his life”—and a quick closing gesture at transience (“before I walked on”). Where the reader should exit the poem, the speaker does, cheating himself and us. The same is true of “Poštolka,” another early poem. Wiman’s assessment of its stance toward life in My Bright Abyss applies equally to “Clearing”: “It’s a rapture of time by someone who never quite enters it, a celebration of life by a man whose mind is tuned only to elegies.” It’s not hard to imagine how such a man could be, in Wiman’s own words, “incapable of love.”

Because love and faith, at least in Wiman’s life, are more than parallel, that deficiency meant he was also insensitive to revelation. In My Bright Abyss, he reflects that his early poems were rife with “unnamed and unnameable absences…as if I were some conquering army of insight seeing, I now see, nothing.” These poems reveal their author’s solipsism, often by their titles alone: “Sweet Nothing”; “Being Serious”; “This Inwardness, This Ice.” And yet, as Wiman observes, many of these are devotional poems, albeit unconsciously so—though the poet denies or flees from the supernatural, the supernatural asserts itself within his lines. When I asked him how this works, Wiman explained, “Poetry gives us a sense of both the reach of our mind and its limitations. I don’t think I would have had any feeling for God, were it not that poems kept showing me some other dimension, as if reality looked back at me, rather than me just going to the edge of reality or seeing into reality. Poetry can both enact those moments and enable them.” He added, “There’s a reason why a third of the Hebrew Bible is in poetry.”

Wiman’s latest and most accomplished collection, Survival Is a Style, is a distillation of the earnest dialogue with faith he began in his 2011 book Every Riven Thing. While there are moments of revelation in the earlier book, they are embattled, almost stammered. It is not until Survival that the poet-speaker dwells comfortably in his faith’s fickleness. The opening line of the poem at the book’s physical and emotional center, “The Parable of Perfect Silence,” is astonishingly straightforward: “Today I woke and believed in nothing.” This is a sentence the younger, less religious Wiman would never have written. The poem goes on to represent a faith Wiman described to me as “small,” “obdurate,” “vertiginous,” “volatile,” and “difficult.” Even today, his experience of God remains not constant or direct, but like, as he writes in “Good Lord the Light,” the “quick coals and crimsons / no one need see / to see” under the surface of a frozen lake. Similar paradoxes abound throughout the collection, whose “Epilogue” summarizes: “The more I feel the more I think / that God himself has brought me to this brink / wherein to have more faith means having less.” It seems that Wiman’s genuine acceptance of paradox—that most Christian of assertions—is what has allowed him space for his unbelief to breathe, with increasing surety, over the past two decades.

*

Wiman’s poetic productivity is impressive—not only given his illness, but also given the editorial and teaching positions in which he has invested so much of himself. There was a time when he wouldn’t consider any job that took time away from his poetry unless he was truly strapped for cash; in a 2001 letter to a friend, the poet August Kleinzahler, he wrote, “I simply don’t let the idea of teaching enter my head.” The same impulse lay behind his plot to quit Poetry and Chicago for rural Tennessee. But when the diagnosis stalled that plan, he gradually warmed up to editing, especially the pleasure of reaching out to poets to accept their poems, though it required taming his aforementioned “cockroach.” “I had to get rid of my ego in that job,” he told me, “and once I figured out how to do that, I was happy.” Similarly, he began to enjoy teaching once he accepted that he taught for his students, not for himself. And yet, while he doesn’t harbor any romantic notions about his teaching feeding his poetry—he still requires “a kind of dead space” in his life to write poems, as he had last year, when he was too sick to teach—he has had several essays grow out of discussions he has shared with students in “Poetry and Faith.” He seems genuinely appreciative of his students’ insights and the personal impact his courses have on many of them.

“Poetry and Faith” can be understood as a project of sharing his intertwined literary and religious struggles with students. The assigned readings consist of poems—many of which have kept him company for decades—that might be read as religious, anti-religious, or somewhere in between. Wiman encourages students to engage personally with the material by having them keep a graded “reading journal” and recite two poems aloud over the course of the semester. Cal Barton ’25, who is taking the course now and described himself as “not religious in any disciplined way,” said he appreciated how the assigned poems encouraged him to think more deeply than he ever had about the nature of faith. He related how Wiman recited “Empathy” by A. E. Stallings on their first day of class, then asked students, who didn’t have the text in front of them, to discuss whether the poem was religious based on the words they recalled. “He’ll nudge you,” Barton said of Wiman, later clarifying in a text message: “It’s in this way that Chris can be quietly radical (though I’m not sure he’d like the word radical): selecting readings that, if read with care, can chip at big, monumental ideas we take for granted.”

As we neared the end of our time together—Wiman had to pick up his fourteen-year-old from school—I was struck by how unrecognizable the man sitting in front of me would be to his twenty-something Guatemala-trekking self. Or, for that matter, to his boyhood self, who said his prayers and claimed to feel God’s presence all too easily in church. The form of Wiman’s forthcoming book, Zero at the Bone, reflects this personal evolution. It not only reconciles different parts of his work, collecting personal and critical essays alongside his poetry and quotes from other writers, but also extends far past the interior to address political and philosophical issues. The poet, professor, editor, and theologian in him seem symbiotic, and his ego seems to have yielded to an ever-broadening gaze. But despite such diffusion, Wiman seems more grounded than at any other time in his life. The key to this groundedness might be another paradox: “If you have a large faith,” he said with a sly smile, “you’re not going to be able to do shit.”