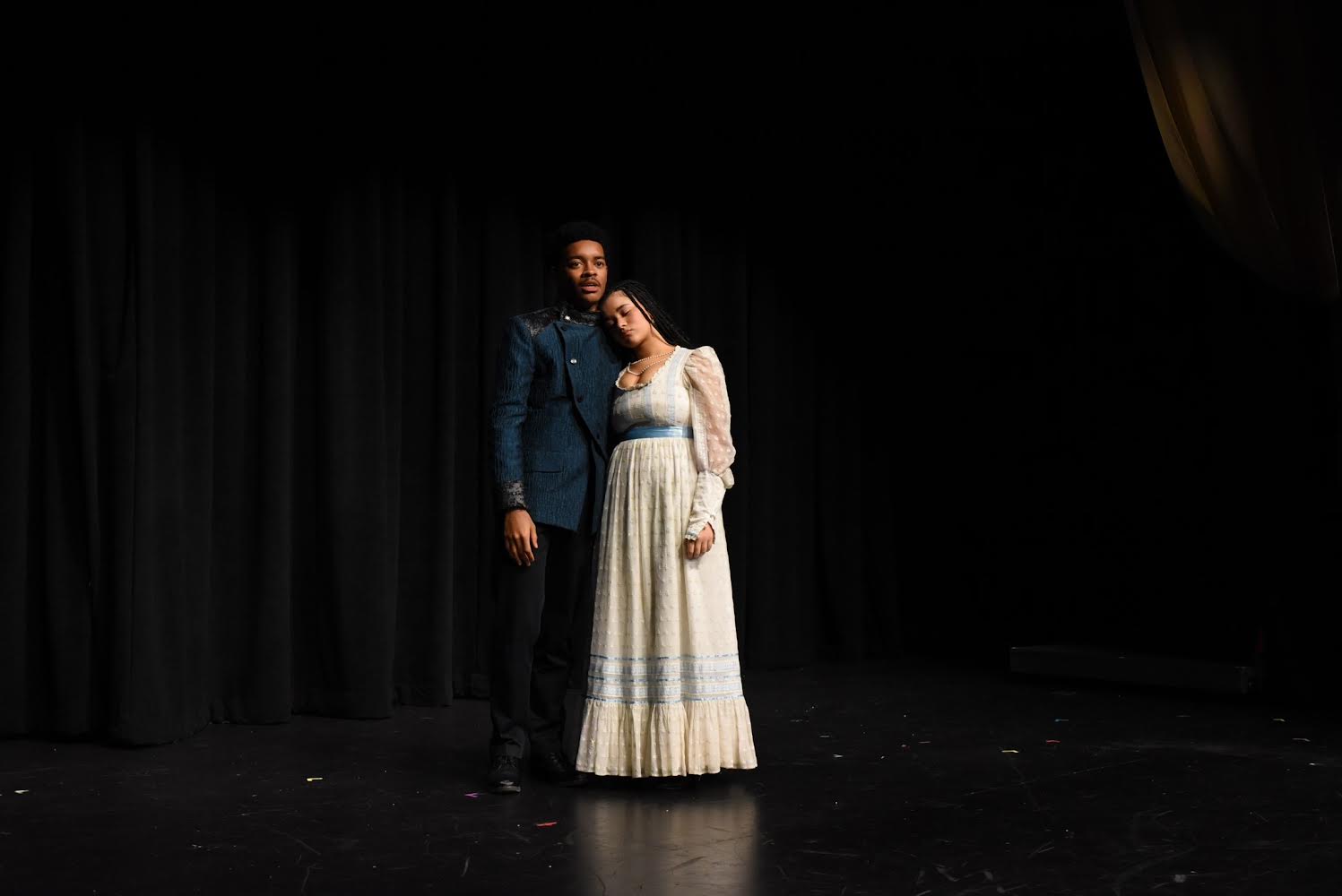

Courtesy of Elio Wentzel

On Nov. 1, the world of Yale drama underwent a small revolution. In the Crescent Underground Theater, the creative crypt tucked beneath the Morse/Stiles fortress, Yale Undergraduate Production staged its most innovative piece of theater this semester — a production so alien, so far out, that it took four hundred years to get here. And we should all be grateful that it finally did.

Although its seeds were sown centuries before, the signs of this innovation first appeared on campus a few months ago, when “Hamlet” began its rehearsal process. Championed by Director Sam Bezilla ’23, Producer Casey Tonnies ’24, Stage Manager Ruoyo Zhou ’27 and star actor Phil Schneider ’24, the production ran from Nov. 1 to 4. It leaned on the financial backing of the Creative and Performing Arts program and the Elizabethan Club, both of which helped this crew raise a sum of just below $2000. While the CPA program is certainly a privilege for any college artist, if this feels like a small number, it’s because it is: thespians at Yale work on a beggared budget.

While citing this as the reason why many plays here are poorly done or hard to watch would certainly be an overly forgiving, albeit conciliatory, suggestion, I’d be remiss if I did not recognize that the show’s meager allowance makes its innovation all the more impressive.

But how exactly was this centuries-old play so innovative? And what does that have to do with Yale drama?

I do not customarily review the shows I see at Yale (though we could use some more critics). I am an actor, a playwright and a producer — at least, I like to think of myself as such. I’ve been a part of several shows at Yale, a number of which have benefited from the aid of CPA grants. In fact, my appreciation for “Hamlet” is anything but unbiased, as I am likely more enamored with Elizabethan drama and classical theater than most of my peers. I am reviewing the show because I think it offers a chance to articulate what only somebody familiar with Yale drama but uninvolved with the production could understand. One could say that I provide an insider’s perspective from the outside. But that would be nonsense.

In my experience, it is largely the belief of contemporary theater-makers that a worthy production of a classical play is one that can take the antiquated text of an obsolete, outmoded or ignorant playwright, bring it to the modern stage and “innovate.” If I’m being honest, I don’t really understand what this entails. I suppose it means that a production must make its text new again, interesting and comprehensible in a way that entertains the modern audience in spite of its boring and cryptic nature.

For now, I’d like to offer a competing definition: dramatic innovation does not deny or rethink the original character of a text. Rather, an innovative play denies and rethinks contemporary theatrical custom. What I mean to say is that, to be radical, a production must go against the grain of what’s conventional in its time — that is, the time of its production, not of its text. If verse drama is the type of the times, a radical would write in prose. If minimalism is all the rave, they would throw in a little song and dance. I’d like to think the minds behind Yale’s “Hamlet” adhere to this definition of innovation.

I see two primary innovators behind the production. Let’s begin with the director.

Bezilla, the first radical, defies the common stock of student and professional theater-makers. His blocking was fluid, his set minimal, his vision simple: communicate the text. He utilized no extraneous spectacle, no irrelevant thematic overtone, no pomp or pageantry. It seemed to me that the director sought to deliver the text in as direct and honest a way as possible.

This is not to say that there was not a directorial presence. Bezilla constantly played with dimensions and shape, seldom placing two actors on the same plane. His actors moved with the volatility exactly appropriate to their character. Schneider’s Hamlet danced across the stage with sudden and intense movements, at every point in accordance with whichever fleeting specter skipped across his vacant mind at that moment of the play. Adrian Rolet’s ’23 King Claudius moved stiffly, at once regal yet unsure of himself, as he grappled with his wicked yet remorseful depravity. The characters frequently clustered. They made contact in moments of familial affection which often verged on the erotic and the rageful, but they sought distance and isolation at moments of loneliness and indignance. The direction was seamless, necessary and frugal. It did not reek of the arrogance of a director who thought they knew something about the text that Shakespeare did not, but rather it displayed the genius of a director who knew the virtues of his script and did not feel the need to distract.

The set was simple, involving a few thrones and movable stones, as well as two rarified built platforms, no doubt to the testament of Producer Tonnies’ technical finesse. The costumes comprised perhaps the largest anachronism of the entire production, drawing inspiration from what appeared to be a Danish court of the 19th century instead of the 16th. With the exception of an unnecessary projection screen looming upstage, every set piece felt vital, every costume tailored, every scene staged to match its form to its function.

Why is this direction innovative? As far as I see it, current theater directors feel the need to introduce sensation and anachronism into their text as a means of sprucing things up and appealing to the commercial craze. This is especially true in classical productions where a director feels that their text’s esotericism must be complemented with glamor. Of course, most theatergoers don’t know much about the theater and are easily entertained. To the extent to which theater is mere amusement, this system works. But in crafting quality drama and honoring classical text, pageantry serves only to distract. What’s more, in a climate obsessed with spectacle and reinvention, the choice to present a to-the-text production that incorporates elucidating movement and deeply honed characterization comprises an enormous risk.

Without Bezilla’s masterful direction and dedicated troupe, the choice would perhaps be boring and trite. Instead, it brought the audience to tears and rejected our contemporary conception of what drama should be. Truly radical stuff.

The second revolutionary of the play comes in its lead actor. Schneider’s portrayal of the Danish prince smacked of incessant preparation and a refusal to throw away a single line. The actor understands that Hamlet’s ramblings do not consist of mere nonsense but of dramatic truth.

While I am nearly certain that Shakespeare’s volatile protagonist cannot ever fully be understood, it is clear to me that Schneider has made a venerable attempt to do so. He wears in his intense physicalization and emotional oscillation the trappings of a methodical actor. And while a lesser artist might have relied on the fanciful crutch of overacting to make up for a misunderstanding of the esoteric diction, we should all be fortunate that Schneider is comfortable enough in his grasp of the language to know his place: as a messenger of the text.

These two innovators are radical in their honesty and simplicity. Of course, this revolutionary approach is a risk: the highs are high, and the lows are low. The direct nature of the attempt allowed excellence to shine through and mediocrity to be, well, laid bare.

When the actors were most on their game, scenes that are typically overlooked felt especially poignant. I am thinking specifically of Mia Rolland’s ’24 portrayal of Queen Gertrude in her devastating breakdown when confronting Hamlet in her closet. There is perhaps no better example of Bezilla clearing the way for his actors to flourish than the chameleonic Leo Egger ’24, whose vocal and physical transformation into Polonius was frankly astounding, at times scene-stealingly hilarious and at others crushingly sincere.

On the other hand, a simple and direct approach to the production left nothing to distract from its sore spots. Apart from Egger and Logan Ledman ’24, the gravedigger, the comedic moments in the show often felt forced and fell flat. One could not help but feel the dramatic suspension dissolve a bit when watching the particularly physical moments, such as the graveside duel of Laertes (played by Prentiss Patrick-Carter ’26) and Hamlet as well as the climactic jousting-match-turned-massacre that ends the play. At times the production lacked unity and coherence. The smaller roles, those of the servants, and the guards, were at times distractingly novice in contrast with some of the bigger players. But in staging a classical play bereft of spectacle and diversion, these weaker elements were inevitably going to stick out. Such is the sacrifice of bare-bones theater.

I left in awe and irritation: awe at the timeless brilliance of Shakespeare’s words; irritation because I did not — and still do not — understand them. I cannot say that I know much at all about “Hamlet,” but I do know this: every time I encounter the play, I feel more and more like an actor. For those who haven’t read or seen “Hamlet,” Shakespeare incorporates a play-within-the-play, in which Hamlet invites a troupe of traveling actors to perform a scene for the court. As the audience and the courtly actors onstage watch the troupe’s performance, one cannot help but realize that, just as the royal bunch is not so different from the traveling troupe, so too are we not so different from the actors themselves. If their world is a theater, so too is ours; if they are actors, so are we. By removing the undue spectacle, the troupe better captured the play’s essence, making this truth more poignant than ever. We were one and the same.

In a modern theater that worships pageantry, an uninventive approach to the text is not only refreshing but risky. The absence of distraction suggests a production team that understands the essence of Shakespeare’s play, that is not so proud as to attempt to change it, and that has such supreme confidence in its actors that it presents them as they are: messengers of the text. Fortunately for this production, the talent of the troupe made it possible to refuse reinvention. And it was precisely this refusal of the common crutch that made the show so radical, so innovative.

Whether or not other theater-makers on campus will heed the call and join the revolution of honest and undistracted artistry is left to be seen. If they all do, perhaps there will be a time when reinvention is innovative, radical and refreshing again — right now, it’s clear to me that it’s not.

But don’t take my word for it. Look no further than the text:

“Hamlet (speaking to the troupe of actors): ‘…suit the action to the word, the word to the action … whose end … was and is, to hold, as ‘twere, the mirror up to nature … Now, this overdone … though it make the unskillful laugh, cannot but make the judicious grieve.’”

Grieve not, judicious reader. You are radical once more.