Yale study examines way to reduce gender wage gap for physicians

A new study discussed how increasing physician productivity might be able to bridge the gender wage gap among physicians.

Annli Zhu

Christine Krueger, a primary care physician at Yale New Haven Hospital, was walking a female patient to the bathroom when the patient broke down in tears.

Until then, the patient said she had avoided crying in a room with the male doctor she had just seen, according to Krueger. Then, on her own with Krueger, Krueger said the patient felt comfortable enough to express herself.

For Krueger, this instance was a prime example of how female doctors can have different relationships with their patients than male doctors.

“We spend a lot more time emotionally supporting our patients, which is how we build trust,” Krueger said. “That’s an example of why I might have a longer [visit] than a male physician, because they walk in the room and they’re getting right to it.”

Women physicians tend to spend more time with their patients than their counterparts, said Ted Melnick, an associate professor of emergency medicine and biostatistics at the School of Medicine.

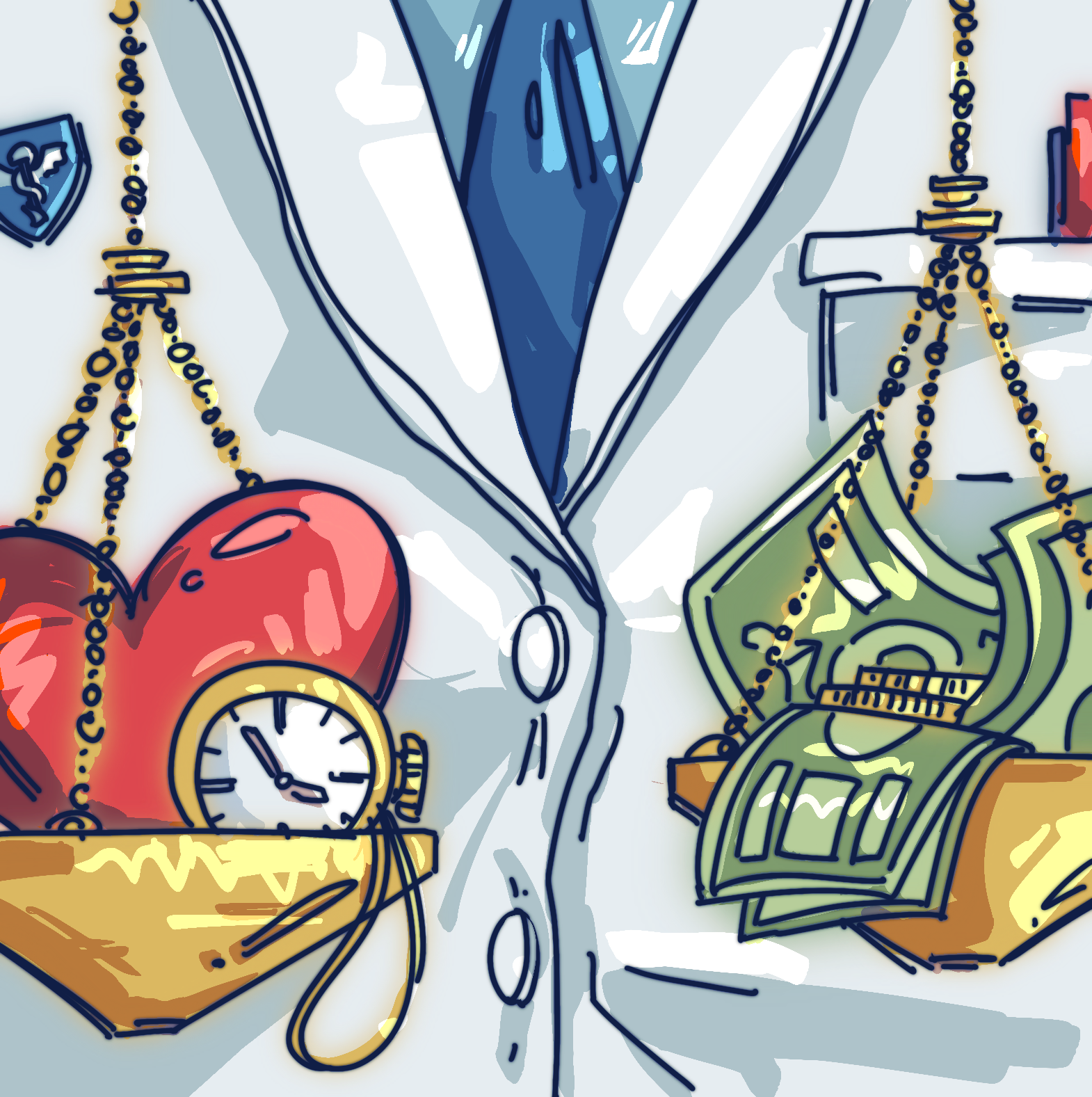

Physicians are largely paid for the services they conduct and not the amount of time they spend with patients, Melnick said. As a result, female physicians, by standard billing codes, are often paid less than male doctors, according to Melnick.

Research suggests that male physicians make far more than their female counterparts — with some estimates suggesting as much as an average of $2 million over their careers.

A recent Yale study published in mid-October found that for general internal medicine physicians, changing policies about doctor’s productivity and medical billing could limit the wage gap between male and female physicians.

By studying doctors in the northeast United States from August 2018 to June 2021, the report also found that the changes could increase overall physician productivity.

“The ultimate goal is to pay physicians not based on the services that they provide, but based on their value,” said Krueger, who was not involved in the study.

The recent study evaluated the impact of a 2021 policy change in billing, called the evaluation and management coding regulations. Issued by the American Medical Association and the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services, the policy update compensated doctors based on their time speaking with a patient, rather than just the number of procedures they conducted.

The report found that, while female doctors had over 22 percent fewer visits than males, their visits were 15 percent longer than their counterparts.

“Historically, E/M codes were attached to procedures that were more valuable or compensated at a better level than things that require cognitive ability,” said Jason Hockenberry, the department chair of health policy at the School of Public Health. “The physicians who were engaged in more of the brain work were not necessarily doing things that were … lucrative from a financial standpoint.”

The study found that policy changes increased female doctors’ calculated productivity value by 17 percent.

The research found that male doctors’ productivity also climbed by 10 percent.

“The new policy is actually helping everyone, especially for female physicians,” said Huan Li GRD ’27, the study’s first author and a doctoral student in computational biology and bioinformatics.

The policy changes also encourage physicians to spend more effort and time on patients, Li said.

For Krueger, building positive patient-physician relationships can be “really valuable” in the long term. The trust a physician can build with their patients translates to better outcomes, she added, whether by helping them adhere to medication plans or stick to a diet.

“Women physicians tend to have better outcomes,” said Melnick, the study’s senior author. “If you take the time to do preventive screening, you can catch things early on, and potentially treat them before they have complications for an individual patient.”

In addition to longer clinical visits, the study also notes that female physicians have generally been found to spend longer on asynchronous work, such as updating electronic health records or responding to messages.

At first, Melnick said, the development of electronic health records was meant to improve patient safety and data sharing. But the actual user experience and the burden of using the system, he said, are “far from ideal” for health care providers.

For Jason Hockenberry, it is a technology issue: the quirks of new software and the electronic health record are “not easy” and have a challenging learning curve, he said. Starting to compensate physicians for their time responding to messages and acclimating to new software, Melnick said, can lead to a win-win situation.

According to Melnick, billing based on time rather than number of visits could also encourage providers to better communicate with their patients — often asynchronously, via messaging on platforms like MyChart.

“Policy change around building messaging your doctor into the compensation model would be another step in the right direction,” says Melnick. “Right now, it’s seen as such a burden because it’s added on top of already really busy hectic schedules.”

Krueger said that physicians are not often paid for their time spent responding to messages.

For female physicians like Krueger, this can often lead to a challenging work-life balance.

“The last time that I looked, I was getting among the most requests and messages of any other physician in the practice,” Krueger said. “I have a lot of trouble balancing the demands of my life as a mother with three children and the demands of work.”

The study also recommended investing in medical scribes — employees who can help physicians update the EHR and take notes during visits — could also improve physician productivity.

For female physicians who take detailed notes, scribes could help alleviate the burden of cumbersome documentation on the EHR.

“If we have scribes, we would not have to spend even more time after the visit, you know, at night in our pajamas on our computers, finishing the charts,” Krueger said.

Even though the study only looked at a single network of physicians, the researchers the News spoke with said they believe that it still offers valuable insights into how policy changes affirm the value of the work that women physicians perform.

The School of Medicine admitted its first female student in 1916.