Fall in love, or don’t: ‘Constellations’ premieres at the Underbrook

“Constellations” explores a relationship across multiple universes and alternate endings.

Jane Park, Contributing Photographer

The first 20 seconds of the play “Constellations” is marked by a long silence, followed by the female lead’s opening line: “Do you know why it’s impossible to lick the tips of your elbows?”

“Constellations,” a 2012 play by British playwright Nick Payne, puts a romantic spin on quantum physics, parallel universes and infinite possibilities. Directed by Carson White ’25, the 75-minute show premiered Thursday, Oct. 12, at the Saybrook College Underbrook.

Following an overarching linear storyline, the play involves two lovers, Marianne and Roland — played by Olivia O’Connor ’24 and Calum Baker ’25, respectively — and shows the progression of their relationship through a sequence of similar scenarios, all ending with alternate outcomes.

“The play shows the power of love and human connection in the face of grief and loss and everything that is hard about the world,” said White. “I think that what sets this play slightly apart from a lot of conventional love stories is you get to see this same relationship equally when it is struggling, when they cannot find connection between the two of them [and] when the world is preventing that. You get to see them on stage overcome that again and again and again.”

According to White, “Constellations” is important to the British playwriting universe because it confronts a prominent question in modern British playwriting: “How does humanity move forward in a world fatigued by human fallibility and excess?”

Payne’s answer? Love.

Marianne, a physicist, often thinks aloud about quantum mechanics and the concept of multiple universes. According to O’Connor, her version of Marianne is socially awkward at times, but fiery and assertive in her relationships. On the other hand, Roland is a beekeeper and “your average guy from the UK,” Baker said.

Costume designer Carter King ’24 did not miss these details when creating a wardrobe for the show. In making Roland’s outfit, King chose a black, double-knee Dickies and a chore coat to allude to the aspect of manual labor in the character’s job, he said. He also perused the websites of several university physics departments to gain inspiration for Marianne’s contemporary, professional look.

All of these outfits were hand-tailored to fit the actors, which King said is an important part of putting on a realistic performance.

“The best way for an actor to embody the character is for the clothes to be real,” King said. “It’s one thing for clothes to come from your closet, then it’s your clothes. But if you come in for tech or for a fitting and it’s totally new clothes that are altered to fit you, then it really helps not only sell it to the audience, but to the actors.”

For a production that plays around with the idea of multiple, disparate universes, it’s important for the “universe shifts” between each scene to be evident and convincing, said lighting director Allison Calkins ’27.

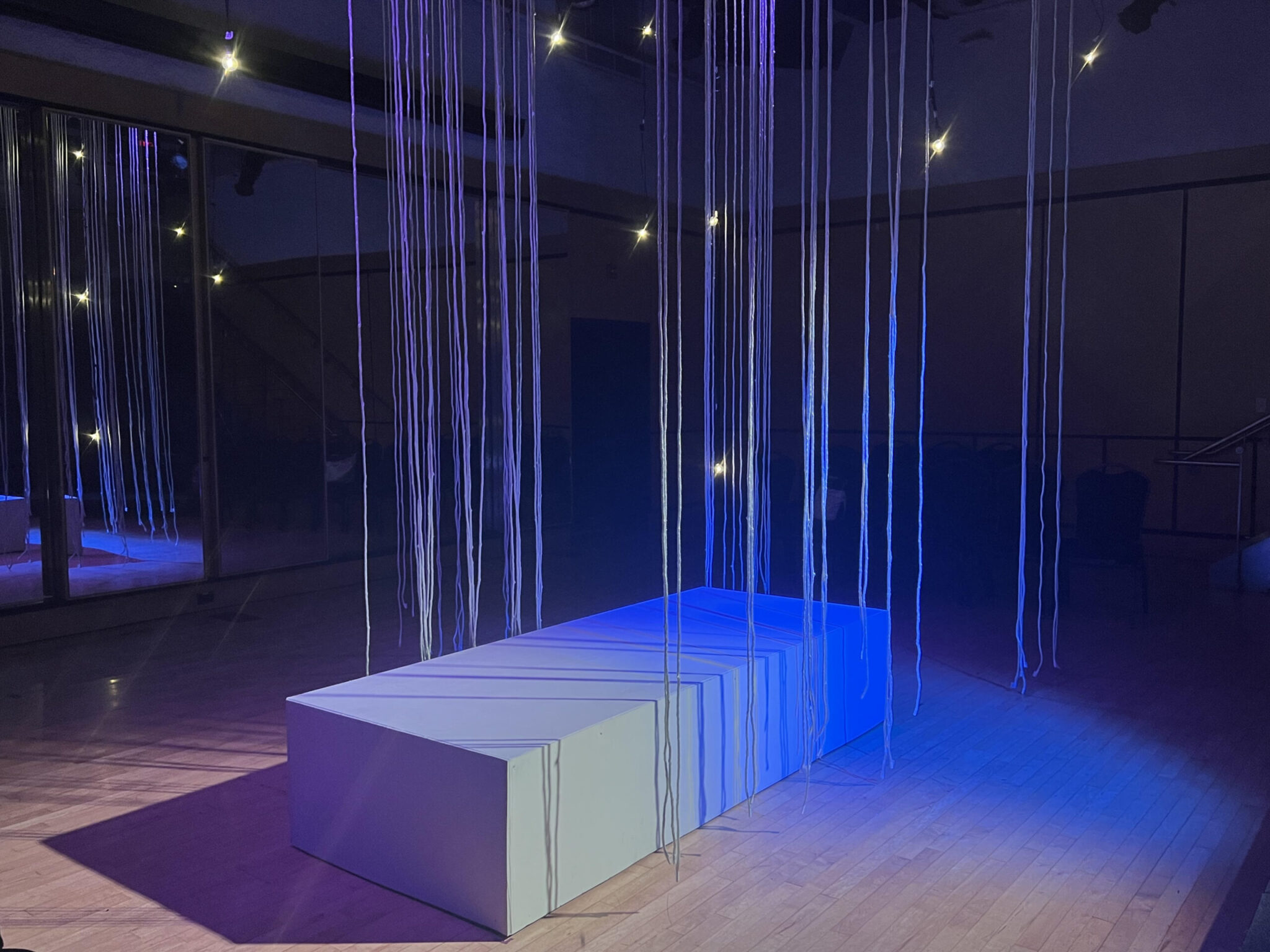

At the center of the stage is a long, rectangular strip, surrounded by wispy strands of white string and variously scattered light bulbs that descend from the ceiling. To cue the “universe shifts,” the stage is flooded with a swirling movement of flickering blue and yellow lights.

“For the universe scenes, I employed a lot of yellow and blue because yellow represents this glimpse of hope while the blue has a bit more of a dreary aesthetic, which is a consistent theme in the production,” said Calkins. “We also have fairy lights, which are meant to look like constellations, as well. Because this play is an abstract setting, incorporating those practicals definitely enhances the experience.”

“Constellations” is not the first time White, O’Connor and Baker have worked together on a production. Yet, White remarked on how this production strayed from conventional rehearsal plans and acting techniques, heavily incorporating improvisation and body-informed practices.

In particular, the production used “analysis through action,” a technique coined by Russian theater practitioner Konstantin Stanislavski. In this exercise, actors analyze the script through a series of “silent études” — when actors explore a text wordlessly, with only movement.

In fact, the opening scene of “Constellations” was shaped by a silent étude from rehearsal, said White.

According to Baker, these exercises helped “key in imagination and play” to the acting process. The silent études and practices helped Baker and O’Connor add their own imprints onto the characters.

At times, O’Connor and Baker practiced scenes without using any of the lines from the script, leaning into their own impulses and instincts to adapt and navigate through these imaginary circumstances.

“I really liked the process of doing études during analysis direction because it’s a lot more actor-driven,” said O’Connor. “It’s driven by your impulses and what you feel is natural to do. It’s a lot easier for performance to come out feeling natural and genuinely motivated emotionally.”

Due to the nature of the show, most scenes have a similar dialogue, with the difference of a word or two. According to the two actors, this made the process of memorization all the more important, as the omission of one word — either intentional or accidental — could change the course of an entire scene.

For some members of the production, the alternate universes in which love falls apart emphasize the moments in which the pair genuinely can love and care for each other. Assistant director Asavari Saigal ’26 finds “Constellations” to be more than an unconventional love story, as she thinks it might not even be a love story at all.

“For me, it’s a show about two people, whose love isn’t meant to be and it’s all the more precious for it,” said Saigal. “You have to remember someone’s sister’s name, you have to know how to hold your temper or be understanding, and that’s what gets you to love, right? It’s a little bit about luck and it’s a little bit about you, but love isn’t guaranteed because there’s no such thing as meant to be.”

“Constellations” first premiered in January 2012 at the Royal Court Theatre in London, England.