After years of advocacy, Yale posthumously honors Reverends Pennington and Crummell

The University held a posthumous degree conferral for the late Rev. James W.C. Pennington and Rev. Alexander Crummell Thursday evening.

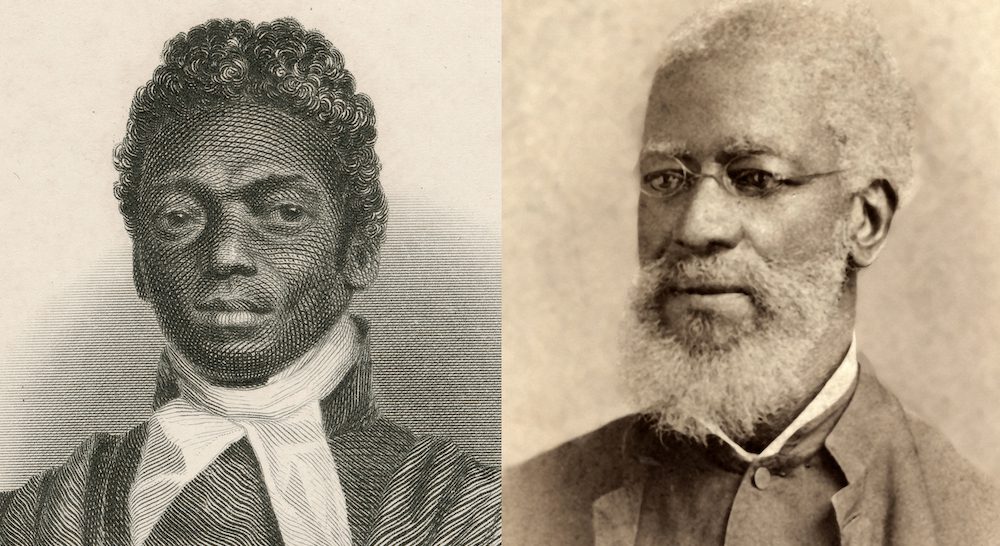

Courtesy of Yale Office of Public Affairs & Communications

Following years of advocacy by students and alumni at Yale, especially from the Yale Divinity School, the University honored the late Rev. James W.C. Pennington and Rev. Alexander Crummell, who attended Yale Theological Seminary, with honorary master’s degrees Thursday evening.

The posthumous degree conferral for Pennington and Crummell was held in the Battell Chapel following a procession from Center Church on the Green. The event was followed by a reception at Commons Dining Hall in the Schwarzman Center.

Pennington was the first Black student known to study at the University at what was once known as the Yale Theological Seminary — now known as the Yale Divinity School — from 1834 to 1837.

Crummell was an Episcopal priest and scholar who also attended the Yale Theological Seminary during the 1840s. Both men studied theology, but Black students at the time were not allowed to formally register as students nor receive a degree. They were also not allowed to participate in class discussions with other students or access library resources.

“It falls on us to reckon with our history. It falls on us to rise to our responsibility and to rectify these wrongs. As a University we have begun to do so. But there is more to do — and more yet to come,” University President Peter Salovey said in his remarks at the event. “Although we cannot return to Reverends Pennington and Crummell the access, privileges and basic decency they were due but deprived of, we recognize this work and honor their legacies by conferring these M.A. Privatim degrees.”

Pennington, who was born into slavery, went on to publish what is considered to be the first African American history textbook in 1841 and an 1849 memoir entitled “Fugitive Blacksmith.” Crummell became the first Black graduate of the University of Cambridge and founded the American Negro Academy in Washington, D.C., where he became the institution’s first president.

The M.A. Privatim degree given to Crummel and Pennington is an honorary master’s degree intended for faculty members who are promoted to full professor but earned their degrees at another institution. According to the event’s program, the Yale Corporation awarded this degree “to individuals who were unable to complete their studies due to special circumstances” in the nineteenth century and provides “resonance” for also honoring Pennington and Crummell.

Dean of the Divinity School Gregory E. Sterling said that he had previously attempted to award Pennington a posthumous degree but faced administrative hurdles which did not allow the University to award posthumous degrees.

Sterling said a history of M.A. Privatim degrees awarded to students who left the University to join the Union Army during the Civil War offered precedent for honoring Pennington and Crummell with the same degrees.

“Sometimes things take a long time, but eventually, the long arc of justice does prevail,” Sterling told the News. “My hope is that we will all be more aggressive in thinking about the wrongs that have been committed in the past, and how we can address those.”

Noah Humphrey GRD ’23, founder of the Pennington Legacy Group which consists of students from the Divinity School, said that he was joined in his efforts by multiple student organizations who worked “behind the scenes.” The Graduate and Professional Student Senate, Yale Divinity Student Government and the Yale College Council have also worked to ensure that Pennington was ultimately honored.

Humphrey said he also called on undergraduate students to recognize their power in being able to create change within the University.

“This couldn’t have been overcome without community,” he said. “ I also call for Yale College students to recognize the power that they have … because the truth is that Yale is heavily directed to undergrad school students and the issue is that when Yale undergraduate students do not recognize the power that they have, the Yale Corporation and other organizations are able to manipulate that and also use it as a way to change how things are run.”

At the event Thursday to honor Pennington and Crummell, Pennington’s great-great-great-granddaughter and great-great-great-great-granddaughter Orisade Awodola and DonYeta Villavaso-Madden, respectively, were both present.

Awodola told the News that she was “touched” by the University’s efforts to “step up to the plate” to recognize Pennington.

Villavaso-Madden said that, to her, the ceremony was a public acknowledgement that Pennington was “partners in success” with other Black historical figures, including Frederick Douglass and Harriett Tubman.

“We have to look backwards to move forward, ” Villavaso-Madden said. “This is not only huge for the University’s history but also healing for our family as well.”

In their decision to honor Pennington and Crummell, announced by University President Peter Salovey in April, the Corporation also considered findings from the Yale and Slavery Working Group, led by David Blight, professor of history, African American studies and American studies.

However, Blight said the decision was not the only result of the YSWG but is part of broader efforts to recognize Yale’s relationship with slavery.

“This posthumous awarding of honorary degrees is one small way that the University can begin to try to repair the past,” he said. “It’s part of the responses to this larger project of Yale deciding officially to study its deep past.”

The YSWG wrote the book “Yale and Slavery: A History,” which is set to be published in February 2024. The book is principally authored by Blight but was also authored by Michael Morand, director of community engagement at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, and Hope McGrath, lead researcher of the Yale and Slavery Research Group.

Blight said that when President Salovey asked him to lead and write a study on Yale’s historical ties to slavery in 2021, Blight suggested early on to go beyond writing a report on the matter, as other Universities have done. He said that the goal of the book is to provide a “real narrative history” that could be widely read by alumni, students and members of the general public.

“Everybody’s gonna have their own reaction,” Blight said. “You’re part of this place forever, and it has a deep and long history that will inform people and make people stronger [not] just going to make people hurt.”

The work of the group, Blight added, was done with funding that was only allocated as salary for research assistants, and Blight himself received no money for his work by choice.

Everyone who did work on the project, Blight said, did it “on their own time.”

“I didn’t want even the perception that I was making some fee off of Yale’s story,” Blight said.

Blight added that there was money given to the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance and Abolition, which he directs, to support the work of his staff who helped to manage the project.

The Yale and Slavery Working Group was announced by Salovey on Oct. 14, 2020.