Beinecke displays 1300-year-old Japanese scroll, one of world’s oldest printed objects

The Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscripts Library hopes its almost 1300-year-old Japanese scroll, the Hyakumantō Darani, tells a more complete story about the history of printing.

Andrik Garcia Higareda, Contributing Photographer

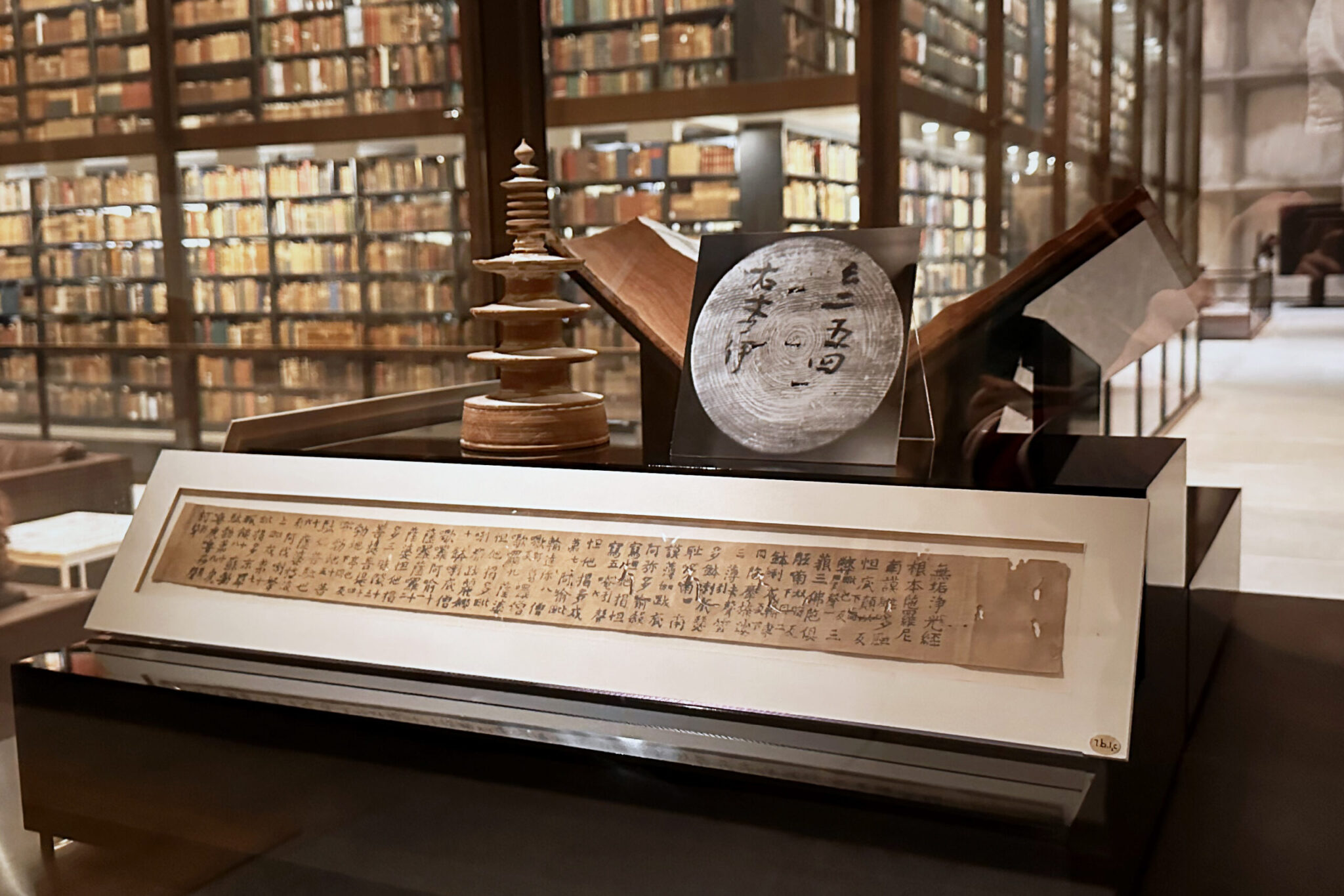

The Hyakumantō Darani, which is regarded as one of the world’s earliest known printed objects, was added to the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscripts Library’s main exhibition hall on Jan. 24.

The Hyakumantō Darani was first acquired by history professor Kan’ichi Asakawa in 1934 through his role as the University’s founding Chinese and Japanese collections curator. The Beinecke is displaying the scroll to honor Asakawa’s intent for its to be viewed and admired by the library’s visitors, according to Associate University Librarian for Special Collections and Beinecke Library Director Michelle Light.

“People appreciate the chance to contemplate two momentous historical objects at once — from different time periods, parts of the world and faith traditions, but each so important to the history of printing and print culture,” Light told the News. “It has been great to see people looking at the case closely and sharing their observations with their companions.”

The Hyakumantō Darani’s history helps explain the development of printing technology. The woodblock-print scroll was printed between 764 and 770 C.E. and was housed inside of a miniature wooden pagoda. The scroll was part of a major project commissioned by Empress Kōken of Japan, which involved the creation of one million scrolls and corresponding pagodas with Buddhist incantations to be distributed to temples.

The scroll and its wooden pagoda are displayed next to one of 21 complete copies of the Gutenberg Bible, which was printed in 1454 by Johannes Gutenberg using metal movable-type.

“I’m really pleased at the thought of this pairing … because so often, artifacts from East Asia and other non-Euro American cultures are exhibited and analyzed in isolation,” said Sumitomo Professor Emeritus of East Asian languages and literatures and former Head of Saybrook College Edward Kamens. “But sometimes it’s really helpful to put them into juxtapositions with monuments of European and Euro-American culture. I think we start asking all different kinds of questions when we look at them side by side with objects from other cultures.”

Kamens also said that the juxtaposition of the two artifacts brings out characteristics useful for his teaching and research. He said that studying Japanese texts and artifacts in relation to those from other cultures offers opportunities to capture the objects’ origins and receptions over time.

He and Haruko Nakamura, librarian for Japanese studies, were consulted on how to convey the Hyakumantō Darani’s complex history. Scholars still debate the status of woodblock printing following the empress’ commission of the Hyakumantō Daranis.

“Material cultural studies or historical studies are really not necessarily [examining] what was done or made, but what was preserved,” said Denise Leidy, curator of Asian art at the Yale University Art Gallery. “So it’s true that there is not much, that there is … these darani and the Korean Diamond Sutra … and there is clearly evidence for printing in East Asia in a Buddhist context at a certain point in time, and then there isn’t so much but I’m not convinced that it fell off. I just think it might have not been saved.”

Light said the scrolls are often used for classroom teaching, adding that it is a great thing to now have them on view to the public regularly.

“I am grateful to my colleagues in preservation and conservation who make sure our collections are both accessible now and taken care of for future generations to engage,” Light said. “They do a great job of making sure the Gutenberg Bible, the Japanese scrolls and all our collections are well cared for and accessible for generations to appreciate long into the future.”

The Beinecke Library’s main exhibition hall is visited by around 150,000 people each year.