Ariane de Gennaro

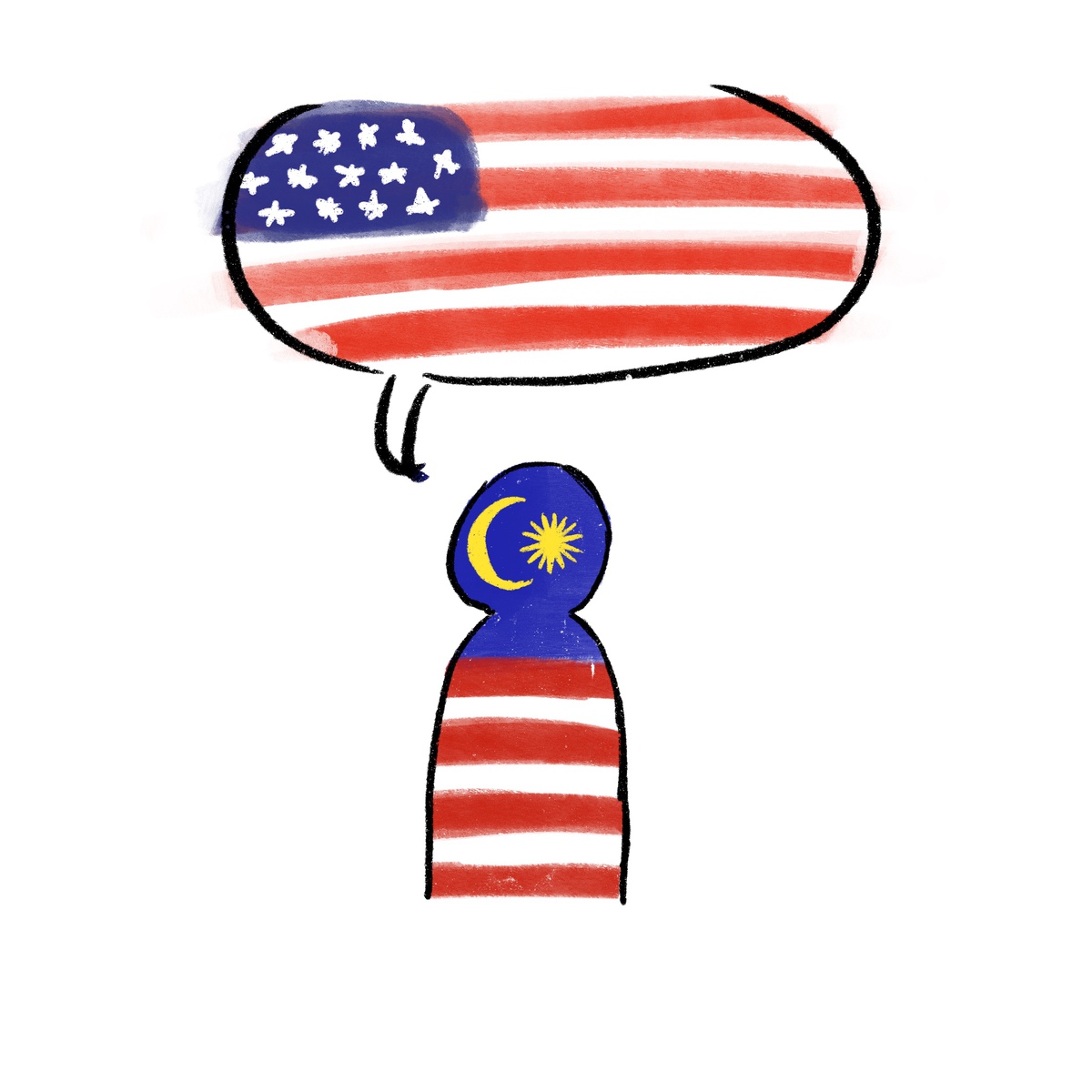

Before coming to Yale, I was faced with a question that first years don’t usually think about:

Do I need to change the way I speak?

I had spent almost all my life in Malaysia. I spoke English that absorbed sounds from Mandarin at school, Malay in the streets and Cantonese and Hokkien at home. I watched the same Cartoon Network shows and Marvel movies that American kids grew up on, and though conscious of the difference in their speech, I saw no issue with the English I had spoken to friends and family.

I became conscious of my accent when I moved to Singapore to attend 11th grade at an international school. My classmates, most of them the children of expatriates, spoke with a blended, American-British-Australian tone, otherwise known as the “international school accent.” The local accent, similar to the one I had, was foreign to them. Despite this, many of them still attempted it, toying with the idea of ‘going native.’

There was no need for me to adopt their speech, but as an anxious latecomer to the school, I was scared of sticking out. I told myself to lay out and avoid suspicion by mimicking my peers. I spent too much time thinking about the pronunciation of words and syllables, fearing the smallest slip ups and feeling embarrassed whenever I said something differently.

When I got to Yale, I brought the accent I had developed in high school. While I didn’t necessarily fear judgment from other Yalies for sounding foreign, I assumed that most Americans would be more receptive to me if I had sounded more like them.

I collected bits and pieces of American English from friends as time passed. I corrected my “clementeens” to “clementines” and my “herbal” to “errbal.” I absorbed some regional phrases into my vocabulary too — but not without stumbling along the way. I didn’t always get things right the first time; I once went into the winter cold with some friends from New York City and told them I was “bricked up” instead of “bricked.” I didn’t understand why they were so horrified until much later.

When I first came to Yale, I loved asking strangers to guess where I’m from to break the ice at parties. They tended to point to a city in the Northeast or somewhere along the California coast. One of my friends spent the entirety of freshman fall thinking I was from Michigan, because I never told her the real answer.

Then, I started to realize how sad the whole thing was. My friends from Texas and Minnesota have regional accents that tell stories about the places and people they grew up with. My accent, which I cannot even bear to call my own, contains no multitudes. It places me in the vague nothingness of Nowhere, USA – a country that I might not call home.

I haven’t completely lost the accent I grew up with. This past break, I went home for the first time since I left for Yale and almost immediately recovered the Malaysian accent that had been in hibernation. In the sole presence of other Malaysians, I felt no obligation to hold myself to strict syntax rules and unfamiliar pronunciations. I would throw a couple Malay words or Hokkien phrases into English sentences while speaking to friends and relatives. I had taught myself to lose my accent, so to embrace it with such ease this time feels like an act of liberation.

There comes a time when I might come back to my Malaysian accent. But for now, I think I’ve grown into the accent that my friends at Yale know me for. I might not always say things the right way, but perhaps the occasional slip-ups should be excused. They’re an important part of my story.