Gavin Guerrette, Photography Editor

Yale is a small city. Its stone buildings tower high above the rest of surrounding Downtown New Haven. The throngs of students walking between classes are its citizens.

There’s another city not far away. Many of its stone towers have the same names as Yale’s: Phelps, Morse, Woolsey, Whitney, Bingham, Trumbull. Wide avenues named after hardwood trees— Cedar, Maple, Magnolia, Cypress— connect to side streets for pedestrian traffic. It can be challenging to find a place to live in this city; the lots for sale are easier to purchase if you already know someone living nearby. Living here, though, is worth the cost. The city is beautifully and carefully planned and prides itself on greenery, celebrity, and a sense of community. It is a fine place in which respectable people might happily find themselves. The dynasties reach their ends as you near the cold sandstone city limits and the fringes are sparsely filled by those without connection. Once someone moves here, they never leave. Who would want to, in a seemingly perfect town such as this?

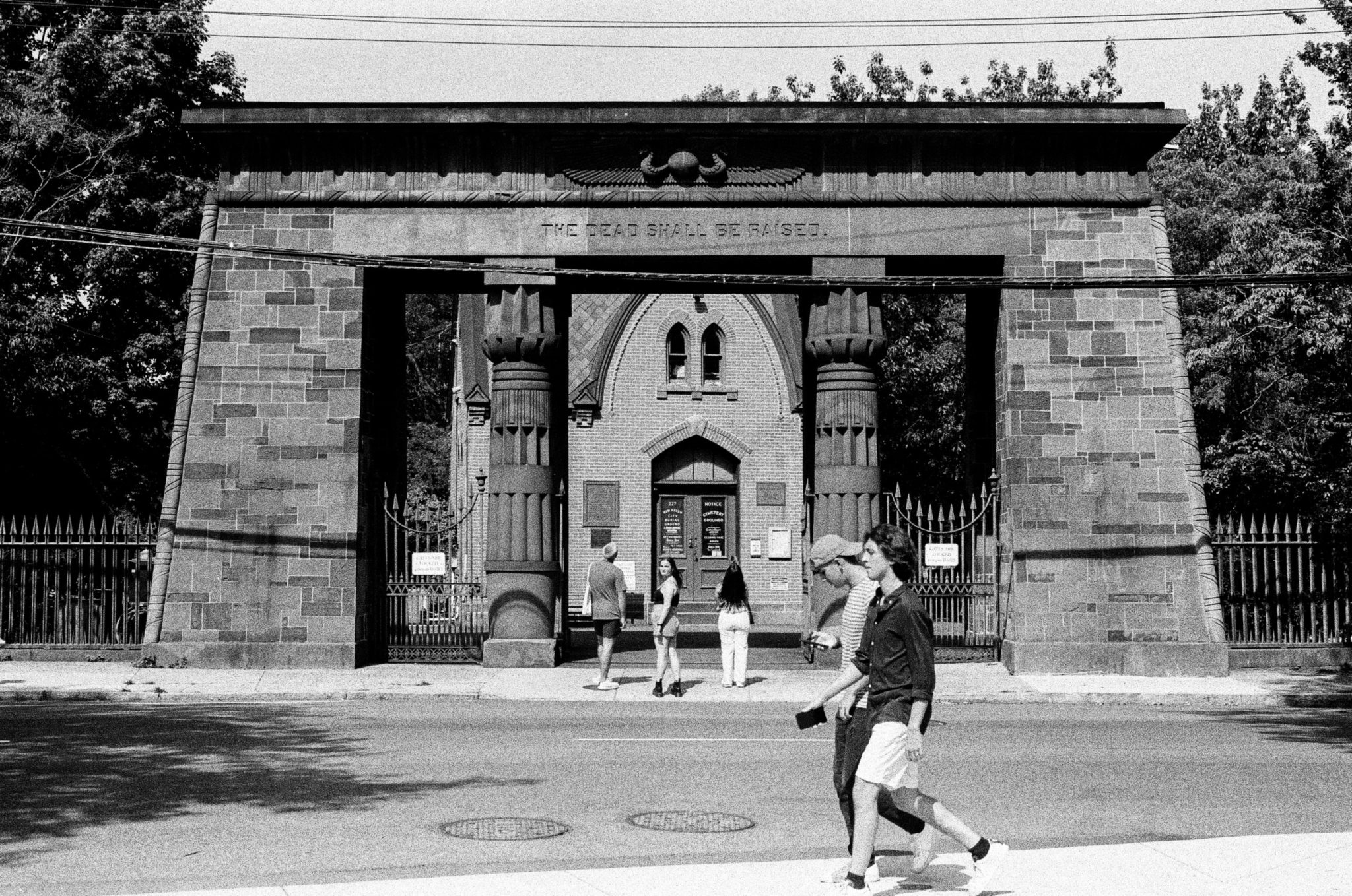

This city is the Grove Street Cemetery. “The Dead Shall Be Raised” is its rallying cry. This Corinthians verse clashes with the Egyptian-inspired Pharaonic gate that opens into this world. The brick office behind the gate offers several pamphlets for visitors. There is one for bench markers, another for an arboretum tour outlining the 40 species of intentionally planted Northeastern trees, a glossed trifold with Civil War soldiers, and, finally, a solemn inquiry form for new burials. They all smell like cigarettes.

The Yale- Grove Street Connection

Seasonal displays seen from the walk up Prospect Street initially lure many students to the cemetery. Magnolias, cherries, and dogwood trees create pink canopies in the spring, and yellow ginkgo and maple chase each other through the aptly named avenues in autumn. James Hillhouse of Hillhouse Avenue fame (and early American politician-real-estate-developer extraordinaire in New Haven) first planted poplars throughout the cemetery at the time of its founding as part of the mid-nineteenth century “rural” cemetery movement. Burial went from being utilitarian and efficient to a more beautiful process that emphasized individuality through the planning of a cemetery. The utilitarian New Haven Green, which held space for 144,000 bodies, was succeeded by the organized and aestheticized New Haven Burial Ground (now Grove Street). Proponents of the movement believed that turning cemeteries into quasi-parks would allow more people to enjoy these occupied spaces and emphasize their gravity as resting places.

Motifs throughout the 18 acres speak to historical representations of the transition between life and death. A metal moth sculpture sits atop the visitor center, a reminder of the cyclical nature of life and metamorphosis—the change from one state to another. There is no cemetery without life in the first place. Sphinx statues stare at an awkwardly placed street sign on the side of the cemetery that runs along Lock Street, depicting the boundary between man and animal. Old headstones once carved with skulls representing the gruesomeness of death lean against identical headstones carved with angels to show the sanctity of life. The strongest contradiction here, though, is that between Yale and Grove Street. Where does one end and the other begin?

Grove Street Cemetery was founded in 1796, 93 years after Yale. At the time of its construction, the school went as far north as Elm Street. The institution continued to expand upwards as opposed to further into urban New Haven. ‘Science Hill’ was first used in its current iteration in the twenties. Ezra Stiles and Morse College were constructed to its left in the sixties. Yale completed its total envelopment of the cemetery in 2017 with the opening of the newest residential colleges at the corner of Canal and Prospect. An angel statue watches over a bench headstone engraved with “in a field of memories we meet every day.” For years the angel held a candle. Now she holds a rolled-up copy of the Yale Daily News.

Students, too, are a reminder of Yale’s presence at Grove Street. Molly Hill ’25, a sophomore in Yale College, finds solace in the trees. An avid birder, she has been going to the cemetery about twice a month since starting college last year. She typically sees common grackles and robins, though she likes the bluejays best. She has frequented Grove Street enough to notice the White-throated sparrows that seldom appear, and only in the winter. “I see more birds if I go to further places like East Rock or Lighthouse Point… but probably the biggest difference is that the cemetery is a cemetery, so even if I’m birding, you can’t help but think a little bit about death while you’re there,” Hill says, softening her voice at the word “death.” She first went to the cemetery to take a picture of the grave of Josiah Willard Gibbs, a decorated Yale professor and pivotal theorist of thermodynamics who developed “Gibbs Free Energy.” She reflected on the celebrated scientist and sent the picture to her father, a chemistry professor, and started to explore the grounds. For Hill, Grove Street is an escape from the hectic hustle of school. “Sometimes I go by myself pretty strictly to bird, sometimes I go to write poetry, or write kind of anything vaguely. Something about it is pretty peaceful.” She shares that cemeteries are well known spots within the birding community, as they are often the only serene places in chaotic urban environments such as Yale and New Haven. Life floods and populates this graveyard. Those who take special note are privy to it.

No matter a student’s academic focus, the cemetery is surely home to a Yale notable in their field of interest. Hill first went to the cemetery to visit Gibbs. At his grave, students and passersby leave rocks and pennies as visitation gifts in line with Gibbs’s Jewish faith. Many offerings come from those wishing to do well on their exams, praying to the “chemistry gods” to look favorably upon them. History and English students may visit the cemetery to see Lyman Beecher, father of Harriet Beecher Stowe. For those interested in science and medicine, the school’s fraught history with the cemetery is enough motivation to visit. Yale’s Medical School was initially built where Sheffield-Sterling-Strathcona Hall is— just an intersection away from the cemetery. John Warner, Chair of the History of Medicine, mentioned Yale Medical School’s resurrectionist history to his Western Medicine class earlier this fall. In 1824, the body of 19-year-old Bathsheva Smith went missing from her grave at the West Haven Cemetery. Suspicions turned to the medical school, especially with Grove Street Cemetery so near. It made sense that medical students needed a way to obtain cadavers for anatomical practice. In the 19th century, resurrection— otherwise known as grave robbing— became a trend at medical schools, and Smith’s body was found buried in a small mound at the corner of Prospect, on the medical school grounds. Riots broke out over the academic desecration of resting corpses. “The mob on the Green threatened to storm the medical school.” Warner elaborated, “[Connecticut] Governor Oliver Wolcott Jr. called the Connecticut Militia to read the Riot Act, or else the militia would charge, and the crowd dissipated.”

A new law was then passed in the State Assembly, “An Act to Prevent the Disinterment of Deceased Bodies.” Rumors spread of tunnels connecting the Medical School to Grove Street. Professional grave-robbing died down with the new act, but suspicions of Yale’s use of the cemetery remained. When asked to expand on the relationship between Grove Street and the medical school, Warner noted an old practice of students meeting at the grave of Nathan Smith —the founder of the medical school—once a year at midnight. He paused before he spoke again: “What happened at Smith’s grave, I have no idea.”

“The walk along Prospect Street— that’s the most peaceful part of my day” sophomore Chela Simon-Trench said. “It’s what separates me at home versus me at school.” Chela loves Grove Street. She has a favorite tree and a favorite bench, but she has been promised that their locations shall not be revealed here. When she was first assigned to live in Benjamin Franklin College as an incoming student, she was intrigued and somewhat concerned by the fact that a cemetery would be the thing separating her from the rest of campus, but she has now found solace in it. On walks home when the gate is open, she dances through the graveyard. One thing she notes is that “[Grove Street] does not feel like Yale.”

“Did you know it’s designed to look like a city?” she asks, information she unearthed while researching for an Art History class. Maybe it can simultaneously be a city on its own, and a piece of New Haven, without being solely a small town in the province of Yale.

The Urban Design of Grove Street’s Hidden City

Cedar Street, an avenue running vertically within the cemetery, was once referred to as “the Street of Dignitaries’, housing the remains of many of the school’s celebrity figures and their families. In the likeness of a city, this is the “nice neighborhood.” Families share unified plots, and their gravestones are grandiose. Cedar houses the corpses of multiple former presidents of the University, including Jedediah Morse, Eli Whitney, and Benjamin Silliman— names that Yale-affiliates would recognize. These individuals are synonymous with the school’s ornate buildings and prestigious programs. In Grove Street, the people of Yale may even see something to aspire to. Walking through the small, planned city is a museum-like display of Yale’s cultivated historical identity. Yale’s elitism is preserved in the center, surrounded on all sides by the bones of residents whom history has forgotten.

A spot at Grove Street comes with a cost and requires connections. The cost of a full grave today is $7,500 ($9,500 including the burial fee). These now-available plots are mostly on the outskirts of the cemetery, far from Cedar. To be placed with the “dignitaries” there would have to be open space, and much more importantly, relation. Like Yale, the cemetery is big on family. A shared last name is a gateway to many opportunities, and a beautiful burial site is one of them. Still, name can only go so far. Grove Street maintains that anybody can be buried there. The cemetery is always expanding, and more names continue to be added around its open edges.

The cemetery will never be fully congruous with Yale. It is surrounded by the University, and its sandstone walls can feel like an imperious break in the bastion of learning and community many envision Yale to be. Let us return to the 2008 proposal of Pauli Murray and Benjamin Franklin, termed the ‘New Colleges:’ perfect examples of how the school can both use Grove Street Cemetery to house its identity and ignore it when necessary. This is a case where the cemetery is not Yale and rather an entity obstructing Yale’s physical identity. At the 1997 bicentennial celebration of the graveyard, the University’s then president, Richard Levin, jokingly countered “The Dead Shall be Raised” with “[it] certainly shall if Yale ever needs the property.” He was still the leader of the school when architect Robert Stern proposed the plans for the New Colleges. Even though the proposal observed the divine nature of the graveyard, the team leading the project wanted to tear down the sandstone walls, replace them with iron gates, and open up the back of the cemetery to create a path through. This was met with protest from the city’s Urban Design League, Historical Society, Preservation Trust, and citizens. Significant not only because of those resting there, but also as the first planned cemetery in the United States, Grove Street needed to be preserved. Yale does not have a claim over these lives, and what is best for the institution isn’t always what is best for the city. The proposal was eventually dropped. The new colleges were built without a pathway, and Prospect Street remains the only path to the new colleges.

“It’s not Yale. Of course, we associate it with Yale, because you can’t divide Yale from New Haven,” said Elihu Rubin, Professor of Architecture and American Studies. The New Haven Burial Ground represents northern expansion of the city away from the Green, when most development was happening at Long Wharf. Neighborhoods and parts of the city developed by James Hillhouse created a sense of organization and social zoning. Rubin says one of the “unintended upshots” of Yale’s recent developments is that more students get to enjoy this space because it is so present. So, whether you envision Yale as the city you roam, or you see yourself as a citizen of New Haven, Grove Street Cemetery is always there. As Professor Rubin puts it, the cemetery is an embodiment of peace and the sacred, “a place in the eye of the storm: outside of things, but at the heart of things.”

This article is part of the November issue of the Yale Daily News Magazine. Read the rest of the issue here.