Q-House hosts celebration of life for Black Panther George Edwards

The longtime activist fought for racial justice and community welfare

Sadie Bograd, Contributing Photographer

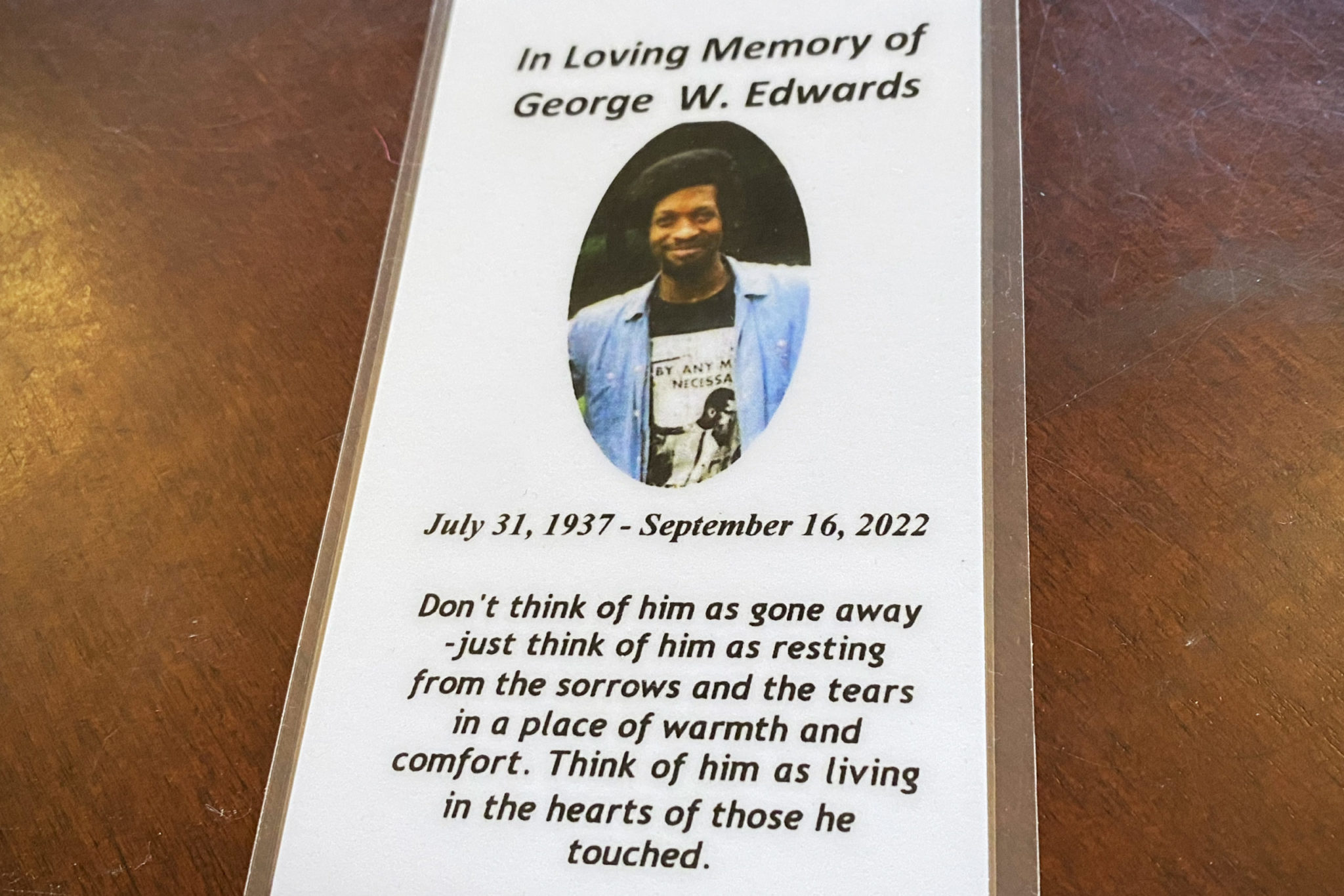

Around 100 people gathered in the Dixwell Community House — or the Q-House — on Saturday to celebrate the life and legacy of one of New Haven’s most prominent activists, George Edwards.

Edwards, who passed away on Sept. 16 at the age of 85, was one of the first members of New Haven’s chapter of the Black Panther Party. After coming to Connecticut to attend the Yale School of Drama, Edwards played a key role in establishing the chapter’s free breakfast program. He was also involved in the city’s first needle exchange program during the AIDS epidemic, anti-apartheid advocacy and countless other initiatives.

The memorial was a joyful event, full of drumming and clapping. Friends and family remembered the charisma, intelligence and community spirit of a man who many people described as “a pillar of the community.”

“He was so committed to liberation for people worldwide,” said Edwards’ partner, Elise Browne. “No matter where it was in the world, he identified with people who were struggling for self-determination and liberation. And this is what he shared with all of us.”

When the New Haven chapter of the Black Panther Party was established in 1969, Edwards was one of its earliest members. Numerous friends spoke about Edwards’ dedication to political action and to helping the community.

Brian Jarawa Gray, who led a drum performance at the memorial, remembered Edwards asking him if he wanted to learn how to protect himself. Jarawa expected that Edwards would give him guns.

Instead, he said, Edwards took him to his office and pulled out some books.

“He gave me a political education,” Jarawa said.

Friend and musical performer Ed Beverly pointed out that when he met Edwards in the 1970s, New Haven — and the Dixwell neighborhood in particular — was facing a range of economic and political issues, from high rates of poverty to police violence.

Edwards and other Black Panthers set up free health clinics for sickle cell anemia, educational services for children and other programs to support the working class Black community.

“This was the heart of New Haven,” Beverly said. “This was the ghetto, as they called it. We called it home.”

Others highlighted Edwards’ focus on global issues. Rosemari Mealy said that Edwards was an “internationalist.” He subscribed to the newspaper of the African National Congress and pushed Yale to divest from apartheid-era South Africa.

Speakers also described Edwards as compelling, compassionate and studious. Browne called him “loquacious,” saying he had a “knack with people.”

Judge Clifton Graves said that when he invited Edwards to his Gateway Community College class to speak about his time as a Black Panther, his students were “in awe.” The talk was so popular, Graves had to have Edwards back a second time.

“He shared his knowledge and information, and inspired and motivated these young people,” Graves said.

Friends also remembered Edwards for his paranoia, although his suspicions were often well-founded. Edwards was the target of a massive illegal wiretapping scheme, part of the FBI’s effort to undermine the Black Panthers organization nationally. Graves recalled how Edwards always wanted to meet outside, suspecting hidden cameras and microphones.

Edwards also faced betrayal from fellow Black Panthers.

In 1969, the New Haven chapter of the Black Panthers tortured and murdered Alex Rackley, who was wrongly suspected of being a police informant. When Edwards refused to participate, he was also tortured, although he escaped before he could be killed.

Edwards, along with other party members, was then charged for Rackley’s murder. Prosecutors also tried to use the case to imprison party leaders Ericka Huggins and Bobby Seale, in an evidently biased trial which sparked New Haven’s 1970 May Day protests in support of the Black Panthers.

Edwards continued to identify with the party, even once it had mostly collapsed under the aggressive FBI campaign.

Graves recalled that when he described Edwards as a “former” Black Panther, Edwards was sure to correct him. During a eulogy by Cyril Innis, Jr., about fifteen members of the audience raised their hands to indicate their affiliation with the Black Panther Party.

Later in life, Edwards was known for distributing personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Jarawa also recalled Edwards’s love of nature, evidenced both by his long walks in Edgewood Park and by his commitment to environmental organizations like Greenpeace.

Multiple speakers called on the audience to continue Edwards’ legacy of activism.

“There’s no retirement from the movement,” said activist and former alder Shafiq Abdussabur, whose mother was a Black Panther. “We just keep doing it until we can’t do it no more, like George did. So I think if we all want to honor George, don’t give up the fight.”

The memorial also saw musical performances, including a rendition of the Marvin Gaye song “What’s Going On” at the memorial by Beverly.

Edwards was born on July 31, 1937, in Goldsboro, N.C.