INSIGHT: Tenant Chemistry

With unorthodox advocacy and organizing tools, the Connecticut Tenants Union is paving the way for a national movement to shift the power balance of American housing. But can they build the community necessary to succeed?

In late August, 2021, in an eight-sided gazebo at the corner of New Haven’s Edgewood Park, 41-year-old Alex Speiser joined a new organizing drive in what he described as a “leap of faith.” It was early evening, humid, and the weather was soupy. Speiser, a high school English teacher in Darien, Connecticut, walked from his home through New Haven’s Westville neighborhood, where he was due to meet three tenant organizers. They belonged to the Central Connecticut branch of the Democratic Socialists of America, and they intended to prepare a half-dozen novices, Speiser included, for a “deep canvass.” Instead of a pitch to join a cause, the organizers wanted to knock doors, hear residents’ anger about poor housing conditions, and identify potential leaders among the tenants who could join future organizing efforts. “We tried some role-play by acting out scenarios between tenants and canvassers,” one of the organizers, Luke Melonakos-Harrison, recalled later. “I think we’ve refined our talking points since then.”

Speiser, who often pairs tortoise-shell eyeglasses with a plaid shirt and jeans, avoided get-out-the-vote efforts in the past, feeling that the easy sells of preachy politicos too closely resembled snake oil. The listening approach seemed more respectful and less intimidating. He was surprised by the intimacy of the Westville door-knocking. “I could hear the fear of those answering their doors, sometimes not even opening them, or opening just a crack,” he said. Some tenants in his first building were willing to share stories of rent hikes and maintenance delays. In other units, though, all he could do was peek through the dark door slits leading to darker hallways, punctuated by flickering lights and the intermittent beeping of expired fire alarms. He suspected that people hid the truth when they said, “Oh, everything’s fine.”

That first gathering in Edgewood Park led to a weekly canvassing routine, and that routine represented the “embryonic stages,” in Speiser’s words, of a full-fledged Connecticut Tenants’ Union, also known as CTTU, now one of just a handful of statewide “tenant unions” in America. A loose coalition of renters’ associations, individual tenants and erstwhile labor organizers, the CTTU is part of a broader movement to shift power from landlords to tenants caught in the squeeze of American housing, through ‘tenant unions,’ which have emerged in more than a few U.S. cities since 2020. Renters who belong to the union “demand stronger rights for stronger rights for tenants; an end to displacement, landlord harassment, and eviction; and democratic control of our housing,” according to the group’s website.

Even among other tenant unions, the CTTU stands out for its willingness to embrace heterodoxy. Theirs is a process of constant experimentation, mixing political lobbying with digital media savvy, avoiding the pitfalls of risky rent strikes, taking advantage of public hearings and under-resourced city agencies. Most central to their cause, though, is efforts to form community between neighbors in dilapidated apartments — classes of renters who, despite living down the hallway or across the street as tenants of the region’s several mega-landlords, have often never met.

Speiser describes himself as a once “typical liberal Democrat” who shifted course after Sen. Bernie Sanders’ first presidential run in 2016. In the aftermath of that campaign, he is convinced that the tenant union offers one alternative vision for grassroots politics — especially since he’s met Melonakos-Harrison, whose friendship has proven especially fruitful for experimenting. “One year ago, I knocked on my first door,” Speiser told me. “I would never have guessed I’d be here, still doing this, today.”

A NATIONAL RENT EMERGENCY

In 2020, in the wake of national eviction moratoriums, shutdowns of utilities and maintenance offices, and calls to cancel rent, new “tenant unions” formed in Boston, Los Angeles, Kansas City, Washington, D.C. and notably, New Haven, to protect renters. In New Haven’s metropolitan area, where low- and middle-income residents suffered from poorly maintained housing stock long before the COVID-19 pandemic began, the demand for change was particularly acute.

The attraction of a tenant union is similar to a labor union, at least in theory. Together, tenants provide a collective power that individual attempts to address housing concerns can scarcely match. Collective bargaining can also mean leverage over one’s landlord, if tenant union members were willing to withhold some degree of rent in exchange for demands.

Yet differences between labor and tenant power can make the latter far more precarious. Tenants can’t appeal to a federal agency for registration and protection of a union in the way that employees can, through the National Labor Relations Board, after an election to unionize. In most U.S. municipalities, city governments and landlords have no obligation to recognize a renter’s association—and rent strikes can be remedied in some states, depending on their eviction and retaliation laws, by replacing the unruliest tenants with others who are quietly willing to pay. The biggest difference may be that tenants in a building, by paying rent, are consumers of a good rather than workers employed to produce that good. In that sense, they have more in common with the consumer protection organizations that serve as watchdogs over banking and credit, consumer privacy, or food inspections.

Rent, of course, is no mere bank withdrawal or food inspection. The intimacy of home can’t be replicated as easily as switching one credit card company for another. To lose that intimacy, against your consent — notwithstanding the scarring effect of an eviction notice or late payment on your credit score — can potentially mean losing your health, your humanity, your life.

In July, 2018, Greta Blau, a six-year tenant in an apartment complex named Seramonte Estates in Hamden, began to document numerous health and safety hazards in her building: toxic black mold, flooded basements and front doors that didn’t lock. Blau, who is 54, has asthma and received treatment for breast cancer during the pandemic. She notified a Hamden health maintenance inspector, Ryan Currier, about the hazards in June 2021. Currier told her to inform Northpoint, the owner of the complex. Mold and water damage continued to appear, Blau told me, in units where families with young children lived.

“We were trying to figure out how to do this when I started reading about one of the Brooklyn tenant unions,” Blau’s husband, Paul Boudreau, recalled. The couple reached out to Justin Farmer, one of Hamden’s city councilors and a member of Central Connecticut’s DSA, with the idea of forming a similar organization. Farmer connected them to Melonakos-Harrison.

Before his involvement in tenant organizing, Luke Melonakos-Harrison DIV ’23 was an outreach worker for unsheltered individuals in San Diego, California. The position consisted of “trying to put Band-Aids on the gaping wounds of our society — of chronic street homelessness,” he said. He recalled that, once he found his clients a new home, the case management didn’t stop: landlord neglect, and routinely dismal public housing conditions, were the root problem. “You wouldn’t believe how many of these houses had bedbugs,” he said.

Redirecting his attention toward prevention before case management, Melanakos-Harrison joined what later became the Connecticut Tenants’ Union in late 2020. At that point, the organization was a mere outgrowth of Central Connecticut DSA’s housing justice working group. At the time, the prospect of a broader, state-wide tenant union seemed “a daunting task,” he said, given that no examples of such a group existed.

But interest was rising. In March 2021, one organizer, Alex Kolokotronis GRD ’23, who studies political theory, put together a history lesson tracing a century of activism in New York’s urban housing districts on the Connecticut DSA’s Youtube channel. In America, Kolokotronis noted, tenant unions were at least as old as tenement housing itself. The former resulted from the latter’s overcrowding, as rising rents and poor health conditions in New York’s immigrant-dominated tenements spurred radical political organizing in the early twentieth century. “We are asking you not to hire rooms in that house,” residents of the Lower East Side wrote in 1904 on a sidewalk card, in Yiddish and English, during a general rent strike led by young Jewish women. “We want to put a stop to it once and for all. Keep away.”

By January of the next year, the renters at Seramonte Estates, led by Blau and Boudreau, began to organize. In February, they hosted their first canvass. While the temperature was freezing, Blau said, “It was really surprising, because I liked it.” Many of the residents were isolated in the complex, and “it was amazing to talk to somebody who’s so alone. Today, membership in the union at Seramonte Estates encompasses more than 250 tenants.

An Experiment in New Haven

For a DSA-born alliance of graduate students, labor organizers and low-income renters, the rekindled interest in tenant unions around the country — as well as local independent efforts like those of Seramonte Estates — offered sources of insight. The Connecticut organizers invited a speaker from the Greater Boston Tenants Union to compare strategies and provide training. They consulted a thirty-page handbook entitled “No Job, No Rent: Ten Months of Organizing the Tenant Struggle,” created by Stomp Out Slumlords, a D.C. tenant union and advocacy group that formed in 2018. The handbook bemoaned “the rituals of liberal NGO politics,” celebrating instead a “capacity for direct action” and change driven from below— capacities that also appealed to tenant organizations across Connecticut.

The handbook’s assumption that more radical, grassroots tenant unions would clash with other NGOs was perhaps unsurprising, given its origins; Stomp Out Slumlords themselves left the D.C. Tenants Union in September 2020, due to creative differences. Yet their strategy of going it alone was risky, particularly when rent strikes were involved. On the one hand, strikes in D.C. were successful in bringing the attention of media and public officials to poor housing conditions — or at least, they were during an eviction moratorium dating to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Once those moratoriums ended, the costs for tenants who participated in a strike grew: eviction, an affected credit report, a lawsuit from their landlord to obtain the leftover rent.

The Connecticut organizers suspected that New Haven could present a smoother route. In D.C., “you couldn’t just call up your Alder like you can in New Haven and set up a meeting,” Melanakos-Harrison said. “Here, there’s thirty of them in a small little town.” With fewer degrees of separation between Alders, tenants, and city agencies, more avenues and levers of power were available to tenant organizers — fines, court filings, and calls for greater regulatory funding. Once the Connecticut eviction moratorium expired in June 2021, the union would need any institutional leverage that it could find.

Building that leverage would mean targeting two institutions: the Livable City Initiative, also known as LCI, and Connecticut’s Fair Rent Commissions, both of which are present in New Haven and some surrounding towns. LCI, New Haven’s housing code enforcement agency, provided tenants an avenue for filing individual complaints about housing codes and conditions — although timely response and enforcement was another story. The Fair Rent Commission, formed in 1984 to “control and eliminate excessive rental charges on residential housing,” according to the city’s website, can initiate a public hearing, after a tenant files a complaint. While a complaint is under consideration, the Commission can choose to suspend payments or freeze a tenant’s rent to its former amount before the increase.

The CTTU sees both agencies, with respect to their funding, personnel, and legal powers, as potential levers that can shift power into tenants’ favor when grievances or rent increases arise. Melonakos-Harrison thought the Fair Rent Commission was particularly under-utilized: in 2020, the Commission finally hired another employee in what was previously a one-person office.

As I spoke to more organizers, another difference of New Haven struck me besides the city’s size: the structure of the property market was distinct from larger cities too. Extractive landlords are abundant in New York and Los Angeles, but those cities are large enough that no one (or two, or three) property owners can corner the market quite like they can in New Haven. For the past decade, housing in Connecticut’s third-largest city has been dominated by three competing firms: Ocean, Pike and Mandy Management. As the New Haven Independent reported this March, Mandy Management affiliates purchased 558 apartments in New Haven in 2021; Ocean Management attempted to sell 399. Rentals in New Haven are a seller’s market, even as many properties are labeled as “distressed” housing stock. Low- and middle-income residents, regardless of industry or employment, have little choice but to rent from them.

At first, CTTU membership followed the directions in the “No Job, No Rent” handbook: let tenants take the lead first, and form a union later. By filing individual LCI violations and Fair Rent Commission complaints at the same time, tenants would experience — they hoped — the social chemistry necessary to form a new union, affiliated with CTTU but nonetheless independent. An early victory at Windsor Housing Authority in central Connecticut seemed to confirm the approach. Residents of the building, which largely constituted low-income housing for seniors and persons with disabilities, met with CTTU organizers during a fair rent hearing in Hartford. The residents of Windsor Housing Authority had begun to form a union as early as January. By May 2021, with the help of CTTU, the Windsor tenants accomplished one positive change: the contract of the complex’s executive director, whom they blamed for poor maintenance, was terminated.

CTTU’s advocacy in other arenas also bore significant legislative fruit, boosting morale. On May 27, 2021, a bill to protect the right to counsel in housing courts’ eviction cases in Connecticut, passed both houses of the state’s legislature and arrived on the Governor’s desk. The CTTU had advocated for its passage for five months. “We were sort of riding high on that victory and wanting to get in more grassroots organizing and face-building work and real, you know, bread-and-butter organizing in terms of building working class institutions,” Melonakos-Harrison said.

Eventually, though, the strategy of taking action before forming a union organization fell apart. “The reasons tenants don’t want to submit complaints as individuals are extremely reasonable and rational,” Melanakos-Harrison explained. “Your landlord will know exactly who you are. And if you just call LCI on your own and request inspections, your landlord knows that you did that.” At the Fair Rent Commission in New Haven or Hamden, a tenant who individually filed a complaint would have to face their landlord — or more likely, their landlord’s attorney — alone, and contest the claim. “People intuitively understood how risky that was for their housing situation,” Melanakos-Harrison said. Retaliation did not have to consist of eviction to be risky: it could mean renewed harassment, neglect to attend to repair and maintenance, or even failure to renew a lease.

Igniting the social solidarity necessary to form a union, the organizers realized, required a spark—this time, in the form of CTTU itself. Their second experiment took place at Quinnipiac Gardens, a nine-building mid-century complex in New Haven’s northeasternmost corner, cut off from the rest of the city by the Quinnipiac and Mill rivers. Tenants complained of water damage, black mold, and broken appliances, and demanded repairs done in apartments. In August 2021, the CTTU organized ten members into “a direct action” at Pike International’s headquarters, on Howe Street across the river. They were armed with a petition: fix the mold and water, and put an end to irregular rent increases. Most of all, they wanted a document in hand, their own copy of the report that an inspection occurred.

The union also pivoted to the city for recourse, facilitating the arrival of the Livable Cities Initiative director, Arlevia Samuel, to inspect poor conditions in the cinder-block properties. Eventually the city dedicated a weekly inspector to Quinnipiac Gardens, at a predictable day and time. As the movement bled into November, the union won tenants the right to receive their own regular inspection reports, instead of phoning a number that may never get a callback.

“We’ve just been experimenting with so many different things this year,” Melanakos-Harrison said. Experimentation left him more confident than recalcitrant: he observed that “we aren’t following the Stop Slumlords model as much as I thought we would.” By this summer, he was ready to return to the “No Job, No Rent” handbook with suggestions for improvement.

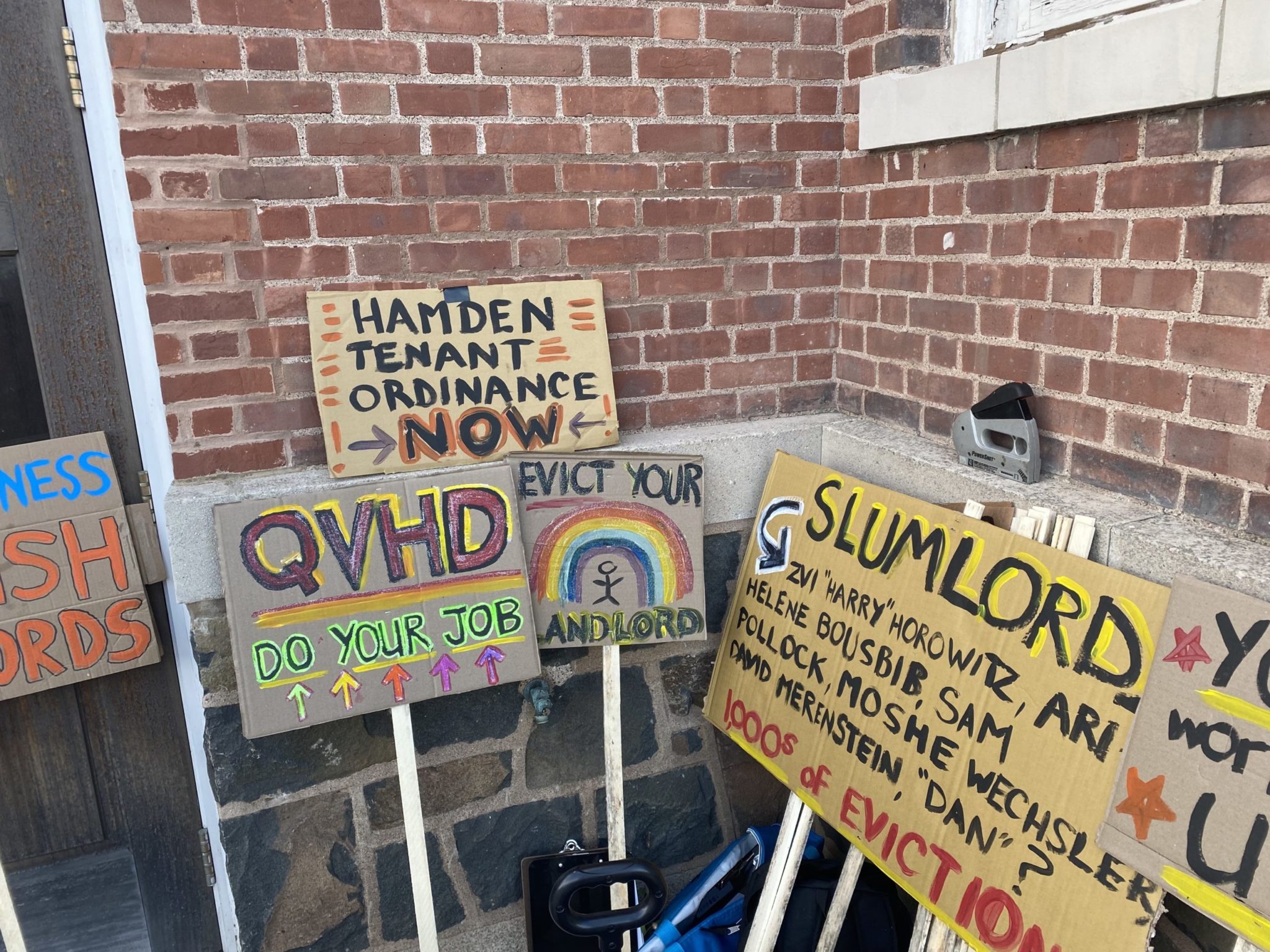

The union’s experimentation often took an aesthetic turn. The two “Ts” in the CTTU logo lean inward, creating the illusion within the logo’s center of a gabled house. On their website, the CTTU offers visitors an array of colorful designer tees and tote bags. One T-shirt reads “Evict Your Landlord!” above a rainbow encompassing New Haven; another, depicting a red-eyed mug surrounded by insects, dons the caption, “We’re Taking Back the Hive!” Melonakos-Harrison drew my attention to the motifs of buzzing, swarming animals throughout the design: thousands of bees, bats and wasps. “Landlords have capital,” he said. “We have people power.”

Hamden’s Push for Dignity

On Sept. 6, the CTTU shared some welcome news on its Twitter account: the New Haven Board of Alders had passed an ordinance to formally recognize would-be tenant unions, provided that a majority of renters voted in support of them. The rule meant that, in Fair Rent Commission proceedings, unions could represent themselves, cooperate in investigations of unfair rent increases, and testify on behalf of their members.

For Blau’s union, the examples set in New Haven inspired similar tactics in Hamden. In a September 15 hearing over Zoom, the city of Hamden hosted its first Fair Rent Commission meeting to hear complaints about unfair rent increases. All the complainants at the hearing were tenants at Seramonte Estates. Blau, Melonakos-Harrison, and other CTTU affiliates attended; they would testify on behalf of the tenants.

The first tenant to speak, Sameed Iqbal, lived in a five-bedroom apartment with his brother’s family and aging parents. He said he faced a rent hike from $2,000 to $3,500, a 75 percent increase. Soon afterward, Kirk Westfall, the attorney representing Northpoint, Seramonte’s property manager, requested to delay the meeting’s conclusion until October, claiming he needed more time to prepare. The delay could mean that Iqbal and the complainants would be liable for September’s increased rent.

“Can I ask a question, please?” Blau interjected. “We’ve been trying to get the management to speak with us since July. Or even before that, I think, June? So that’s been months, and honestly, I don’t think that’s a good reason for a continuance. I also think that we could go forward tonight with our statements, and that we adjourn another day for Mr. Westfall to do his part.” She went on. “My question is, which rents are not going to get raised? Everybody’s? Are they going to continue raising everybody else’s rent?”

“Well, the Fair Rent Commission only has jurisdiction over people who file complaints,” Conte Robinson, a member of the Hamden Commission, said.

“I understand that. We have a lot of other complaints,” said Blau.

“Well, you may have, but the Fair Rent Commission can only deal with the complaints that are before them,” said Robinson.

“We have complaints before the Fair Rent Commission, is what I’m trying to say,” said Blau.

The Commission allowed three of the tenant complainants to testify that night; Melonakos-Harrison served as a Spanish interpreter for one of them. Westfall’s request to delay the determinations was granted, so long as tenants would be spared from rent increases while their cases were considered.

On Sept. 28, at the invitation of Speiser and Melonakos-Harrison, I drove to Hamden, where members of the CTTU’s Seramonte Estates branch, including Blau, were gathered at an intersection in front of the city’s Memorial Town Hall. The Seramonte tenants hoped to attract local support for their usual causes of towing fines and toxic mold, especially from the most prominent invitées: three members of the city council and a State Representative. They also wanted to champion a tenants’ rights ordinance that would follow New Haven’s lead and formally recognize tenant unions in the town’s municipal law, allowing the union to interact with attorneys in Fair Rent Commission procedures. Passing cars honked in support as attendees brandished cardboard signs and leaned others on wooden posts along the Hall’s marble walls to illustrate their grievances: “No More Predatory Towing!” “QVHD, Inspect the Mold!”

Blau took the stand, a red megaphone in her right hand. Her voice didn’t waver. “We are asking our government to prioritize housing as a human right,” she said. “We deserve to have strong roots in our community just like homeowners!” The crowd cheered. State Representative Robyn Porter took the stage, and the mood shifted. Attendees watched, silent with anticipation, while CTTU organizers flitted from newcomer to newcomer, collecting signatures.

“I’ve heard people say ‘pay your rent,’” Porter said. “But I want to ask people: if you were living in chronic conditions that the tenants at Seramonte are living in, would you be paying your rent?” “NO!” the tenants yelled. She closed by giving the audience what they waited for: a personal statement of support for legislation that the Connecticut legislature would consider “in 2023 when we go back in January to address these increases and put a rental cap.”

“Let’s finish strong, y’all,” Melanakos-Harrison said, taking the megaphone. “When I say, ‘What do we want,’ you say, ‘rent control’!”

“What do we want?”

“Rent control!”

“When do we want it?”

“Now!”

I approached Blau toward the end of the rally. We sat on the concrete steps to Memorial Town Hall. Her dark sunglasses, with purple rims and green striped sides, covered a third of her face, which was otherwise framed by gray, tousled hair.

She wiped her eyes underneath the sunglasses, which stayed on. “We’re being evicted,” she said. “Or at least, they’re trying.” The tattoo on her right arm, exposed from carrying the megaphone, was an infinity figure eight.

According to court filings, in July, several months after Blau and her husband formed the Seramonte tenant union, the couple received a “notice to quit” — an eviction notice — from a limited liability company affiliated with Northpoint Management, which owns Seramonte Estates. The LLC claimed the right to evict the couple, on account that they represented a “serious nuisance,” in two counts against Blau and one count against Boudreau. They found counsel in the New Haven Legal Assistance Association, who represented them in a housing court appearance in August.

The lawsuit was not Seramonte’s first involving the couple. In a separate case that began in June, Boudreau sued the Seramonte Estates LLC for negligence after he sustained serious injuries during a fall in the building’s icy parking lot, claiming the property managers failed to maintain it properly. In response, the company blamed Boudreau’s injuries on his negligence while walking across the lot, according to court filings. (The eviction notice arrived less than a month after Boudreau filed his lawsuit.) Both legal cases are ongoing.

Blau wasn’t always sure whether residence at Seramonte Estates was worth the fight, between her asthma and the basement’s black mold and the threats from Northpoint Management. In the past month, though, she has decided to stay put in Hamden, with Boudreau. The organization she put in motion represented too much, and too late, to let go now. I asked her whether the apartment felt like home to her, and she said, “I close my eyes and pretend it’s just a house in the woods.”

She attributed her steadfastness in part to CTTU’s support for their nascent union force. “Luke [Melonakos-Harrison] has been our…” she trailed off, as a tear escaped the protection of her sunglasses. She gestured at the late September air, beginning to chill around us. “Really, you have to have people outside your community backing you up.”

The Next Caper, at Blake Street

At Elizabeth Apartments, a four-building, 70-unit complex in the Beaver Hills neighborhood of New Haven, the CTTU has launched its most recent experiment in tenant protection. The trouble began on January 1st, 2022, when sheets of paper appeared on the front door of each unit in Elizabeth Apartments, indicating that Farnam Realty Group, a local real estate firm, would take over the building’s rentals and leasing. At the time, Farnham was responsible for maintaining properties owned by Ocean Management, a major property owner in New Haven, which had purchased the Elizabeth Apartments complex through an LLC for $9.2 million. By April, Ocean Management began managing the building directly, and renamed it after its street address, 311 Blake Street. At that point, the tenants were informed that Ocean Management had no intention of renewing any of their leases. If the tenants wished to stay, the company wanted them to pay a stiff increase to their rent — and to pay month-to-month, with no guarantee of whether the next month at 311 Blake Street would be their last.

The landlord’s plan was to “buy this place up, renovate, turn it into a much more gentrified apartment complex and attract people who could pay those kinds of prices,” as one tenant, Jessica Stamp, put it. A six-year renter at Blake Street with deep-set eyes and flyaway brown hair, Stamp paid $950 a month for her single-bedroom under Roger Simon, the former owner. She was floored to hear the new prices Ocean proposed in its other properties after renovations — up to $1,895 a month, high for anywhere in New Haven. When she and the other tenants discovered that they risked losing their leases, they decided to form a tenant union.

In July, they requested a meeting with the Ocean property manager and an attorney to discuss the change to their leases. They also had concerns about Blake Street’s dangerous construction and maintenance practices. Despite the master plan to renovate, which involved painting every possible exit to apartment floors at the same time, effectively trapping tenants inside their homes, the management had no plan to fix long-standing issues such as mice infestation, toxic mold, and rotting wood in the floors and windows. One tenant even reported finding mold in clothes stored in the back of her closet, highlighting the severity of the problem. These unresolved issues further fueled the tenants’ determination to push for better living conditions and more transparent communication with the management.

After the meeting, Sarah Giovanniello ’16, a representative of the union — now termed the “Blake Street Tenants’ Union,” with a nod to Ocean’s renaming — contacted the CTTU with a proposal for partnership. To the Blake Street tenants, the CTTU represented a crucial resource for strategy and organizing tips. To the CTTU organizers, their drive showed promise: the tenants had started their union independently, and their landlord was Ocean Management, one of New Haven’s largest and most prolific property owners. The latter fact was convenient because the New Haven ordinance would only recognize a tenant union that included 10 or more units of apartments with the same owner, a description that fit Ocean. The company has been found culpable of 27 criminal housing violations in New Haven since this spring.

The union leaders from each party agreed to host a joint gathering on Blake Street’s home turf, to offer their proposed alliance to broader membership for approval. DSA organizers arrived early to 311 Blake Street, bringing chocolate chip cookies, Dunkin’ Donuts, and nut pastries from Pistachio, a nearby café, for a plastic table reception of hors d’oeuvres.

Speiser brought carrots and pretzel chips. His CTTU responsibilities had thus far consisted of canvassing. The Blake Street visit, just a ten-minute walk from his first canvass on that day in Edgewood Park, would be the first new union meeting he attended: he didn’t know what to expect. Organizers from the CTTU and the Central Connecticut DSA intermingled, arranging fold-up tables and chairs in a grassy clearing tucked behind one of the complex’s four brick buildings.

Stamp brought a fold-up chair of her own. She was wearing flip-flops, exposing toes that she had managed to paint turquoise without leaving behind a single chip. A science teacher at a nearby technical high school, Stamp normally exuded the confidence of someone whose “crazy skills” in managing a classroom translated well to the rap-sheet minutiae of union organizing. Headed into the meeting, she was feeling uncharacteristically anxious. She hadn’t been told the location until the last minute, and worried that “they weren’t actually doing what they said they were gonna be doing — standing up for us and fighting for these things for us.” DSA and CTTU organizers could leave 311 Blake Street the next day, but Jacob Pap, the Blake Street property manager, could dangle a month-to-month renting arrangement and prospects of a renewed lease over her head. Would the union have a plan for those consequences? Jessica Stamp was unwilling to risk diving into conflict without one.

Outside, the DSA organizers gathered in a semicircle before a three-piece poster board. Illustrated on the canvas was a pyramid of social class — “City Government, Mayor, and Board of Alders” on top, “TENANTS,” represented as an army of stick figures lining the bottom — akin to the famous 1911 political cartoon, “Pyramid of a Capitalist System.” Instead of that cartoon’s straightforward hierarchy, though, the CTTU poster was suggestive of the union’s multi-levered, experimental approach. Included within the pyramid were the hard policy levers: making complaints to the Livable City Initiative and Fair Rent Commissions. Encircling the sides were harder-to-quantify social factors: “reputation,” “media attention,” “existing social networks.” They may as well have added their T-shirt sales.

A veteran DSA organizer, Mark Firla, explained that the tenants could have help writing a new lease for themselves, and proposing it to the Ocean managers. He had sought help in the matter from Yale Law School’s Jerome N. Frank Legal Services Organization, which provides pro-bono legal support for public interest cases.

The plan sounded a little half-baked to Jessica Stamp. She had no reservations about piping up: “What are we doing? I feel like we’re floundering here.” The union’s lease-writing activities, she pointed out, could be a red line for Pap and the Ocean Management leadership, who had the potential to outgun the tenant organizers. Shmuel Aizenberg, the principal of the LLC that purchased Elizabeth Apartments, had personally attended the July meeting with Pap; there, he’d boasted to the tenants about the millions in investments on hand to support the Blake Street renovations. Stamp went on to describe her concerns about the union’s leaderless structure — not unrelated to her accidental exclusion from the emailed-out details of the meeting.

For a moment, Firla turned a little red, but he seemed to regain his footing as he paused to consider that the woman in the folding chair facing him might have made a good point. “We are recognizing a union here,” he said, gentle but firm. Declaring as much could come with protection, with New Haven’s new tenant union ordinance.

After the DSA group finished making their appeal, Melonakos-Harrison and Speiser approached the canvas. They explained their history with CTTU, offering affiliation with the broader union and taking the temperature of the dozen-plus gathered tenants. Melonakos-Harrison’s voice rose in pitch, for dramatic effect: “Do you want to join a union of Ocean Tenants?”

The vote was a unanimous yes. Stamp was “in,” although she wasn’t sure about taking a leading role in the new union. Yet the need was obvious, and CTTU organizers were cunningly persuasive. After the meeting, she said, “all these people were trying to talk to me and I felt like I was being recruited, and it turns out I was.” Stamp now describes herself as the “front man” of the Blake Street union, e-mailing weekly missives of the union’s next course of action. Once the afternoon light in October began to wane, she offered to host union meetings in her apartment instead of among the overgrown bushes outside.

Most recently, Stamp has spearheaded a new tactic: encouraging tenants to leave strategic Google Maps reviews that documented Blake Street’s poor conditions to hold Aizenberg and Pap accountable. So far, they have left four reviews, all with one star. The trick was to aim for specific results. Two days after Stamp posted about a broken toilet that had been sitting in the parking lot for four months — “I shouldn’t have to live like this,” she wrote — the toilet, among other subjects of complaint, disappeared.

Stamp’s daily ritual after arriving home from teaching used to be simple: isolate and recuperate. But after joining CTTU, she relished the chance to chat. “Last Saturday, I knocked on every single door in the apartment complex. I probably talked to about 25 people,” she said. “I can’t have a weekend day of just being an isolated hermit. I mean, I like talking to people. I like feeling useful. I like seeing people’s needs get met.”

Her evolution reflected the hopes of CTTU as a whole, which were rarely rewarded with unambiguous success. But they were also far from unfounded. On Oct. 19, after hearing further testimony, including from Melonakos-Harrison, the Hamden Fair Rent Commission voted to freeze rent increases for three of the Seramonte tenants who filed complaints in September. In the wake of the decision, Greta Blau reflected on the psychological relief, after the toll of so much neglect. “It gets very depressing after a while,” she said. “And finally someone’s like, ‘Here’s a way to do this together,’ and then you feel less alone.”