The Lost Cause beneath our feet

Journalistic standards of the 1910s permitted the exact reproduction of speeches without including opposing views or additional context. The News of the day took part in this practice in its coverage of the creation of Yale’s Civil War memorial.

Yale News

In 1865, at the close of the Civil War, Yale was overwhelmingly northern, pro-Lincoln, and anti-slavery. In the 1860 to 1861 academic year, the University was only three percent southern, while nearly 700 students gave their lives to oppose the Confederacy. When the war ended in 1865, Yale considered creating a memorial to these Union soldiers. Other Ivy League universities were already taking the step. In 1866, Brown memorialized its Union dead. In 1874, Harvard followed suit. At the time, creating a memorial was simple; memories of the war had not yet grown apart and crystallized. But Yale’s idea was either lost or abandoned to time. In the years to come, the missing memorial became increasingly hard to ignore. The nation wanted to make sense of the forces that had torn it apart and honor those who had kept it together.

Outside of Yale, a war over history was blazing. It would ignite a myth so pervasive it forgot it was thought up. Three visions emerged out of the Civil War: the reconciliationist, white supremacist, and emancipationist. The first asked the nation to sew up its wounds, the second used terror and violence to maintain a segregated order, and the third lived in African American memory; it saw the war as the rebirth of the republic. The narratives, each alive in memory and jockeying for space in America’s story, would dictate how the nation moved on from the war.

In the wake of the war, Americans had to contend with personal and national tragedy. Nearly 620,000 soldiers had died and people wanted a meaning, a purpose for the scale of the destruction. In this context, the myth of the Lost Cause came alive. It had its origins as a literary and political device in the immediate aftermath of the war. Then, some diehards championed the Confederate cause. Others wistfully recalled the Old South and plantation life.

White southerners depicted the Old South as a natural, glorious society fighting for its morals against an industrialized and encroaching North. The crux of their story was that the Civil War was a fight to preserve the heritage and independence of the Old South. “In attempting to deal with defeat, Southerners created an image of the war as a great heroic epic,” the National Register for Historic Places application for a Confederate statue read. “Like tragic heroes, Southerners had waged a noble but doomed struggle to preserve their superior civilization.” Stung with the shame of defeat, white southerners tried to hold on to all of their old world that they could.

In this context, white southerners continued their horrific violence against Black Americans. The Lost Cause narrative relied on fervent racism. Forced to see their institutions and culture laid low, they rebelled against Black Americans. Vigilantes perpetrated violence against Black people and institutions while attempting to portray themselves as saviors and civilizers. They created mythic horrors of Reconstruction for the purpose of American union, which was built through racial subjugation.

At the time, in 1871, writer and abolitionist Frederick Douglass spoke at Arlington National cemetery. “I may say if this war is to be forgotten, I ask in the name of all things sacred what shall men remember?” Douglass questioned. In his speeches and in newsprint, Douglass tried to preserve the memory of the Civil War. He furthered the simple truth; on the southern side, the Civil War was fought to preserve slavery, not chivalry. Douglass saw the war and emancipation as the rebirth of a nation, as the advent of freedom, citizenship, and dignity for Black Americans. But this could only emerge from accurate memory of and accounting for the past.

Still, Northerners began to adopt the Lost Cause narrative, whether from genuine belief or a desire to reconcile with their countrymen. The elections between 1868 and 1876 saw a drive for peace on the Republican side. The party no longer ran for radical reformation, but campaigned on order and stability. Democrats, by contrast, wanted an immediate reunion predicated on white southern autonomy and supremacy. On July 5, 1875, Douglass spoke outside of Washington, D.C., on the coming of the American centennial, “If war among the whites brought peace and liberty to the blacks, what will peace among the whites bring?” he asked. In the years to come, Douglass would receive an answer: peace among white people meant violent prejudice, fervent segregation, and memorials honoring the men who brought about this terror. By the 1890s, reconciliation won out. The United Daughters of the Confederacy formed in 1894. It influenced school curricula and dedicated memorials to the South. Confederate memorials sprang up across America, unveiled with American and Confederate flags waving in tandem. The country chose reunion over a reckoning with race; it chose to reconcile on terms the South set.

Yale University reflected the national context that surrounded it. As the nation busied itself with a project of memorial construction and commemoration, Yale came into focus as an institution that had not memorialized its veterans. In 1865, when Yale first considered constructing a Civil War memorial, the News referred to the conflict as the war of the “rebellion.” It focused most on honoring Union soldiers. But in 1895, it began looking to the past from the present context. The February 27, 1895 issue of the Yale Daily News featured a top story titled “No Memorial for Them.” The story’s opening paragraph praised the men who gave up their lives in defense of the Union. But the paper listed 100 Yale men who died in the war — including several on the Confederate side.

One year later, reconciliation had fully won out on Yale’s campus. The war’s true cause stayed alive in discrete strains of Black memory. But Yale chose “healing” over truth. On October 3, 1896, the Class Ivy Committee decided to plant two slips of ivy instead of one, as is tradition. They chose one from the grave of General Robert E. Lee and one from the grave of Theodore Winthrop, a Union officer. The metaphor was apparent; as the verdant tendrils from the formerly warring sides grew around each other, so too did Yale hope southern and northern students could come together at the University.

The push towards reconciliation both relied on and led to the construction of memorials commemorating the past. In 1901, Yale proposed an association of alumni to organize Memorial Day celebrations. The first contention was over whether the sons of southern veterans could participate on the committee. The News wrote: “Such men are to be included. A failure to do so would destroy the prime object of the movement.” On the fourth of June 1901, the Memorial Day Association was formed. Less than a decade later, Judge Henry E. Howland, a graduate of the class of 1854, proposed to the committee a memorial for the Yale men who sacrificed their college years to the war.

He admitted that, in the immediate aftermath of the war, it would have been “ill-timed to have suggested that sons of the South should have been remembered in such a memorial.” But the times had changed, he claimed. “When the passions of that time have died away … it seems an appropriate moment to bring before the alumni of Yale the propriety of commemorating the men of both sides who gave their lives in the great struggle,” he wrote. Reconciliation required that Americans obscure the true cause of the war.

Some publications, whether disenchanted with the tales of the Old South or with too sharp of a memory, were holdouts. They noted the strangeness of creating memorials to men who had tried to wrench the country apart. The Boston Globe skeptically reported the announcement that Lee would have his name held up beside Grant and Sherman. An opinion piece in the Cleveland Gazette lamented that the South had won back all that it lost in the Civil War except for its slaves. Though there was a prevailing memory of the Civil War, there was not a universal one. But as time wore on, these skeptics became an ever-shrinking minority.

At Yale, as the war approached its semicentennial, the University had subscribed to the Lost Cause narrative. Yale’s president Arthur T. Hadley praised both Lee and Lincoln as men of principle, while the News joked that the Southern Club would lynch a “n—–” on the Green. People could openly praise the South as men of principle and devotion, though misdirected in what they were devoted to. When Howland made his request for a Yale memorial, a News editorial supported it. North and South could honor “characters and motives,” neglecting sides, the News wrote.

The University was engaged in efforts to become a “national” university. This meant recruiting students from the South and West, urging them to come to Yale and making an environment that accommodated them. As the University began commemorating the war with a memorial, its aim of expansion colored the effort. The committee that planned the memorial folded southern opinion into the memorial’s very foundation, down to how it referred to the war. The South’s preferred moniker was “the war between the states,” which attributed equal responsibility to both sides and obscured the true reason for the war. “The phrase ‘War of the Rebellion’ is in many ways accurate, but it is so distasteful to our Southern friends that it is out of the question,” wrote Anson Phelps Stokes 1896, the University Secretary and a member of the planning committee. The committee settled on the title “civil war.” It was “unobjectionable,” Stokes stated.

The committee contorted itself to keep its southern members and observers contented. Members spent months debating how to display the Union and Confederate names to avoid exhibiting the overwhelming majority of Union veterans. They decided to list veterans from both armies chronologically by class year. Just as the vines of ivy wound around each other, so too were Union and Confederate names intermingled and inseparable. The memorial did not merely recognize that the war had claimed the lives of Yale graduates, it honored them for their faith to their cause — regardless of what that was.

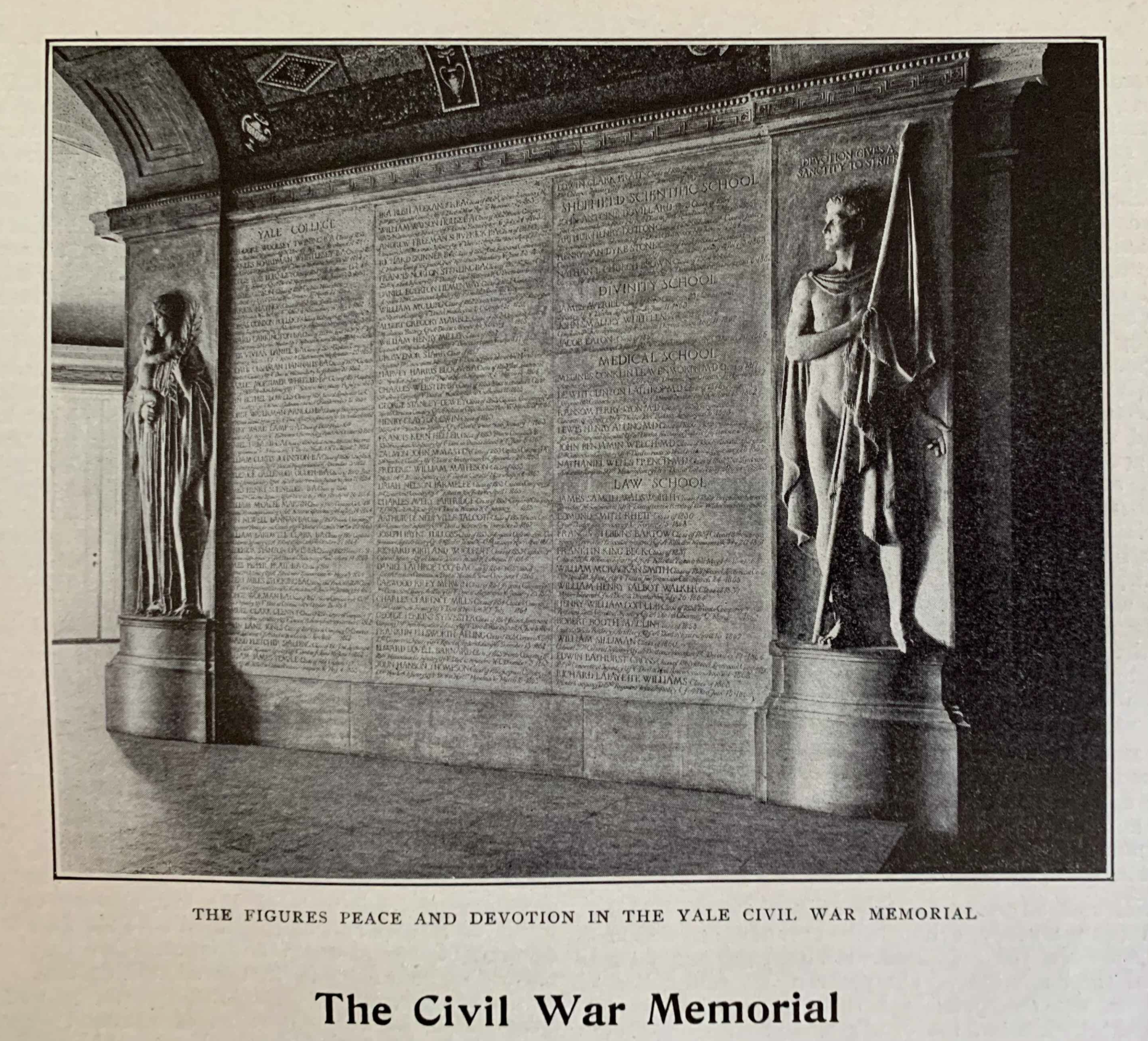

The memorial honored the two sides as equals. Its stated aims were to ensure the memory of Yale men’s sacrifice and to “suggest the change of feeling and sentiment which has come about since the close of the war,” the News quoted Talcott H. Russell 1869, secretary of the memorial committee, as saying. Inscribed into the floor of Woolsey Hall were the words: “Love and Tears for the Blue; Tears and Love for the Gray,” from a famous poem, “The Blue and the Gray,” by a former Yalie. In this placement, they both literally and figuratively served as a foundation for the University. It would be rebuilt out of the dust of both armies, and not out of the memory of emancipation as Douglass had hoped.

Charged with chronicling all that occurred on campus, the News gave full coverage to the June 1915 unveiling and dedication of the memorial. The article, which quoted liberally from the speeches at the dedication ceremony (a common journalistic practice at the time), designated the memorial as “one of the most important monuments that the University possesses.” The News was an active proponent of the memorial. In its editorials, it praised the University for honoring soldiers’ self-sacrifice, regardless of the cause. Though it did include one alumnus’ acerbic letter against the tribute, much of the coverage parroted Yale’s leaders and committee members who were courting southern students and had increased their numbers by 45 percent in the 50 years after the war.

Though the News was in accordance with journalistic standards and public opinion of the time by uncritically advancing the Lost Cause narrative, authors and editors at the News had no sense of true justice or goodness divorced from the context of the age they lived in. By 1915, the Lost Cause ideology reached the apex of its power after attempted advancements by Black people. The press primarily pushed a reconciliationist memory of the war. The New York Times and Washington Post furthered an insidious hybrid of the white supremacist and reconciliationist visions of the war. Still, the News did not push back. It did not search out alternative opinions to publish.

Black newspapers were resentful of this white-dominated coverage. With widespread segregation and frequent lynchings, their strides during Reconstruction were wrenched away and written out of the national memory. With newspapers’ narrow sourcing and direct quotes from speeches, Black people were written out of the news coverage of the time as well. In this respect, the News ultimately perpetuated prejudiced views and a racist rebirth of a nation.

Additional historical research by Steven Rome.