Segregation, Cross Burnings, and “Misguided” Students: The News of the 1950s

In reporting on a cross burning in Silliman College that an administrator portrayed as a “misguided prank,” the News did not provide opposing viewpoints.

Popular media has long characterized the 1950s as a decade of “Happy Days,” “Grease,” malt shops, sock hops and Elvis Presley. But this overlooks the fierce racial tensions of the time. It was the decade of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Brown v. Board of Education and strides in the civil rights movement. While the subject is often taught as a problem confined to the Southern states that had the strictest segregation laws, there was similar racism in many institutions in the North. Civil rights activist Martin Luther King, Jr. described the Northern city of Chicago as “a closed society” that perpetuated “involuntary enslavement” of its Black population. Throughout the 1950s, Yale was largely closed off to non-white students, thereby perpetuating the inequality present across the country. And its student newspaper, the Yale Daily News, often did not adequately cover instances of racial tensions on campus, allowing ideas of racial inferiority to spread and permitting the University to downplay acts of prejudice.

On Feb. 28, 1952, the News reported on a scandal that had swept the nation — a cross burning at Harvard University. The article states that the dean of Harvard announced the two students involved were severely punished, but provides no details as to what form the punishment took. The article goes on to say that Harvard’s administration thought this act “was not intended as a demonstration of racial or religious animosity.” However, the burning occurred in front of the house of nine Black students. And though the News quoted the administration’s point of view, the article’s authors did not include any testimony from the Black students who lived in the house. It is unclear if the News attempted to contact them.

Five years later, on Sept. 25, 1957, a cross was burned in the Silliman College courtyard at Yale University. This was approximately a week after then-President Dwight D. Eisenhower intervened in Little Rock, Arkansas to ensure that Black students could attend newly-integrated schools in the district. The burning appears to be in protest of this historic event as the cross had a cardboard sign bearing “I Like Ike” attached to it. In the News’ article, which was published one day after the cross burning, the authors portrayed the incident as a “misguided prank.” While that may have been the position of the master of Silliman, Luther Noss, and the students the News interviewed, there are no quotes or descriptions of opinions from the few Black students who attended Yale during this time. The Sept. 26 article was the last story the News wrote on the incident, save for a small op-ed from a student who decried the lax position of the administration regarding this issue. While excuses could be made regarding the reporting on Harvard’s cross burning — such as distance, time and resource availability — none can be made for the News’ failing to adequately report on a cross burning in the very heart of Yale’s campus.

Throughout the 1950s, the News published several other articles where it failed to adequately cover race on campus. In the Nov. 15, 1950, issue, the News allowed for the printing of an op-ed piece that claimed segregation was an “essential” part of Southern culture, titling it “Segregation for Keeps!”. In this op-ed, a student claimed that attempts at dismantling segregation would result in pushback that would undo all progress made thus far. One could make the argument that the piece is simply a student exercising their right to have an opinion. And interestingly, southern students at the time thought the News’ editorials, which were critical of segregationist leaders, reflected the view of “sanctimonious northern college editors.” But the same “communications” section that printed a piece calling for segregation to continue features a letter of a student complaining about not getting their desired seats for a Yale-Princeton game. The News placed an opinion piece advocating for segregation to continue alongside a trivial piece.

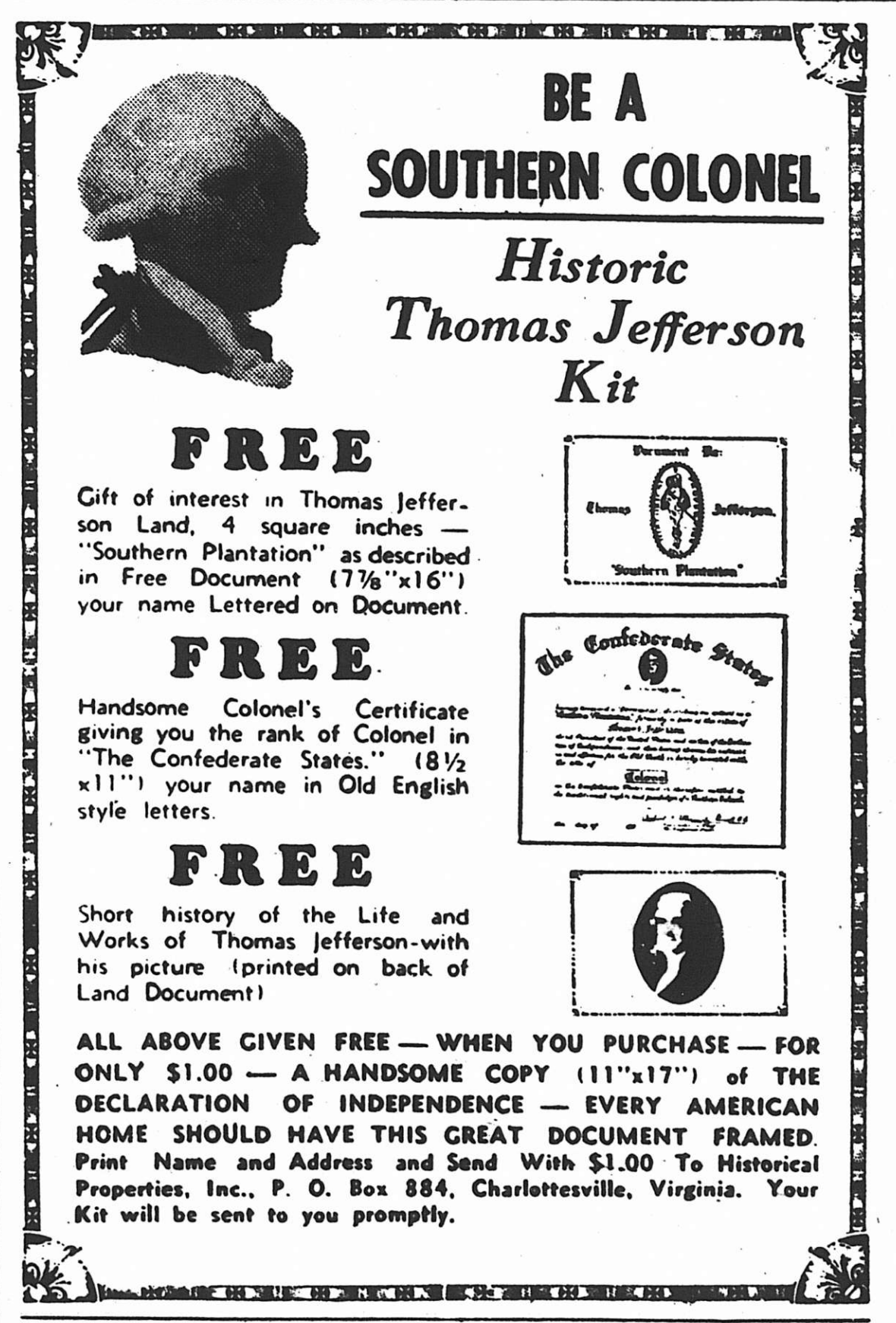

Another example is an article that was essentially an advertisement for an upcoming minstrel show, published in the News on Sept. 30, 1953. A minstrel show was a form of comedic theater in which a white actor dressed in blackface and performed comic skits, dancing and musical performances to depict stereotypes of Black people, such as a lack of intelligence, superstitious beliefs and being lazy. This article was less than 100 words and was not structured as a major story. It included a brief mention of the student’s success at getting the project approved and his difficulty in finding other students interested in participating. The article also notes that he was seeking the help of the News to drum up interest. Knowing this, News editors still decided to publish the piece. Another example is a prominent advertisement in the Dec. 2, 1954 edition that offered the “Historic Thomas Jefferson Kit.” This “kit” promised to make someone a plantation owner and colonel of the Confederate States of America in exchange for $1.00 — now $10.63 — to be used to purchase four square inches of land. This advertisement casually portrayed plantation ownership and slavery, a horror that caused widespread suffering. It is unlikely that the News would have printed this advertisement had it had more input from Black students.

With the rise in racial tensions throughout the 1950s and the beginning of integration nationwide, Yale as a university could have been a leader in this respect. But students are only as informed as their news source allows them to be. As such, the News not only had a journalistic responsibility but a moral one as well to ensure full, critical coverage of instances of racism on Yale’s campus. The failure to do so must be taken as a lesson for all current and future Yale Daily News reporters and editors so that they can succeed where their predecessors so unabashedly failed.

Additional historical research by Steven Rome.