Sophie Henry

For my ninth Christmas, Dad bought me a right-handed Yamaha FG-Junior acoustic guitar. I was left-handed and so furious with my father for handicapping me that for eight months thereafter the guitar leaned against the basement futon, mostly untouched. Mostly.

From time to time — in secret — I’d swipe at the instrument like a curious, unmusical animal. A guitar’s open strings spell E-A-D-G-B-E, and a full strum forms an E-minor-seventh chord with a suspended fourth. Suspended chords demand resolution, and strumming in the violent way non-guitar players always strum in search of it, I pulled the instrument out of tune. One day I tried to pull it back. Instead, I snapped a string.

Dad noticed. The broken string was physical evidence of the interest that I, out of spite, had tried to hide. He swapped the nickel strings for nylon so my un-calloused fingers could press them a bit easier.

My act was waning. Sure, the Yamaha still felt foreign. It was still the wrong way around, and, in any orientation, I still couldn’t play it. But the guitar and I had something in common, something I could no longer deny.

I was a hormonally stunted kid. Dr. Cervantes, my first endocrinologist, had a scatter plot of percentiles for age and height in her office. I hugged the horizontal axis until, at thirteen years old and four feet six inches tall, I began nightly injections of human growth hormone.

The Yamaha, similarly, was three-quarters scale, small. So small that, in my runty hands, it — and I — looked normal.

#

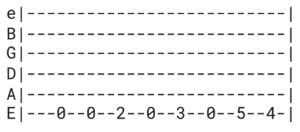

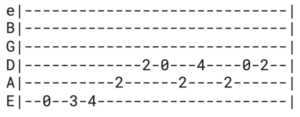

My first guitar lesson was in the living room at 4 p.m. on Wed., August 26, 2009. My teacher, Rob, an old neighborhood rockstar, drew in my notebook a picture of a guitar with its anatomy labeled: headstock, nut, neck, strings, frets, bridge, body. He taught me two riffs and wrote them in tablature notation. The first was Henry Mancini’s theme to “Peter Gunn,” which is little more than a single-string exercise:

The second was The Beatles’ “Day Tripper.” It was a real riff from a real song, one I knew and liked and had already wanted to play. And, in theory at least, I could:

Guitar snobs love to say that “tone is all in the fingers,” that the instrument is little more than an extension of the body — really, the hands. My left hand could only stretch to the fourth fret, and four frets was as many as “Day Tripper” required. I held the pick in my right hand and struck the open E string. It rang. I pressed down on the nylon, my index finger nestled just behind the third fret. I plucked. It rang again, and I felt — to my surprise — my mind and body in something other than conflict.

I fumbled through the song again, and again. Later that night — to my surprise — Dad brought his old warped Yamaha up from the basement and fumbled along with me.

#

Dad’s childhood home is just two blocks from mine. We both grew up in Middle Village, Queens — but in different New Yorks.

Dad’s first favorite song was The Lovin’ Spoonful’s “Do You Believe in Magic,” which came out in November 1965, the month he turned four. When he was eight or nine, he heard Led Zeppelin’s “Whole Lotta Love” on the jukebox in Carlos’ Pizzeria on Metropolitan Avenue. He found a guitar teacher not long thereafter. As an aimless teenager in New York in the 1970s, Dad crawled the club scene. He went to CBGB, to Max’s Kansas City, to every since-shuttered venue imaginable. Twisted Sister, The Ramones, Television, Talking Heads — he saw them all.

I too prowled New York in high school, but urban renewal — and my study habits — foreclosed most opportunities for live music and teenage debauchery. My Jesuit high school jazz band gave us shirts with AMDG — Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam — in the CGBG font across the front. That’s about as close as Dad’s teenage experience and my teenage experience ever got. And for that, he is proud.

Dad was a bad student. He probably had ADHD. He doesn’t know. In the 60s, ADHD was cured with a rap on the knuckles. The unnamed handicap haunted him. It sent him to a technical high school instead of an academic one, and to an extra make-up senior semester thereafter. Sure, he later became an electrician, and a great one at that (construction-site nicknames are notoriously crude, Dad’s was “John the Gentleman”) but Dad the electrician often wonders whether he would have made a great electrical engineer, someone with a desk and a tie and without permanent damage to his hands or elbows or spine. Who knows? Maybe he could have, if only someone had been there to help him along, to push him.

Dad never stopped listening to music, but his high school band fell apart after just a few rehearsals and he quit guitar lessons once easier thrills like cars and girls and parties came around. Loving music and loving a musical instrument are two related but distinct acts. Appreciation comes easy. The latter takes practice, discipline, dedication. It takes a real push.

#

Dad’s first push, when I was five, landed me at soccer practice. I hated soccer. I hated it because — for seven long years, Kindergarten to 6th grade — Dad wouldn’t let me quit. I wanted to quit because I was bad at it, and I was bad at it because I was an osteological six-year-old playing in a nine-year-old boys’ league.

Throughout adolescence, my friends tormented me over my height with the chummy cruelty only children possess; By pubescence, I figured myself vertically castrated. I’d stare in the mirror of the K-Mart fitting room and peer up above my sightline, picturing a normal-sized, normal-shaped me staring back down. Then I’d hang my head and stare at the khaki pooled around my ankles.

Dad never liked the mirror, either. He was a chubby kid. He had asthma that kept him on the couch and away from sports. He liked pretzels too much. When he was a teenager, he found powerlifting and drinking, and for the rest of his life — long after he quit both activities — the resulting weight would oscillate between muscle and fat, but it would never go away.

Sometimes, after dropping me off at soccer practice, Dad would run laps around the park. After practice, he and I would drive home in his rusty Pathfinder. The ride back smelled like sweat and it was silent, save for the radio.

#

The Guitar Center in Long Island City has a parking lot above it and a Chuck-E-Cheese across the hall. It takes an escalator to get in and an echoing stairwell to get out. When I was first learning guitar, Dad and I descended that escalator and climbed those stairs just about every weekend.

We window-shopped. Standing before the great guitar wall, I’d point one out, and Dad would reach up and take it down for me. He’d plug it in, and I’d play.

I was learning fast. Just a few months after “Day Tripper,” I was playing riffs and chords and songs, and even writing my own. I was good. People watched. I was ten, playing like I was fifteen, looking like I was seven. Dad listened, leaning against the stack of amps with a permanent grin.

The Guitar Center in Long Island City is where Dad bought the original Yamaha Junior, back in 2008. In 2012, we bought my second acoustic — another Yamaha, larger and better than the first — also from Guitar Center. That acoustic served me until 2019, when I upgraded yet again. Same store, same brand.

Save for one pathetic southpaw corner, Guitar Center stocked only right-handed instruments. If I had learned to play lefty, my in-store selection would have been dismal; my chances of finding a good used guitar on Craigslist, slim; and my ability to hop over to a friend’s house and pick up his guitar and play, non-existent. Had Dad capitulated and bought me a lefty guitar, had he allowed me the easier thrill, he would have been setting me up for a life of needless musical difficulty.

Dad never stopped pushing. He just got better at discerning where pressure was effective, where pressure was needed.

#

When I first left for college and Connecticut, Dad and I started texting on a nightly basis, trading YouTube links as currency. I would try to impart my college-educated aesthetic sensibilities with showtunes and art rock. He would send back whatever he had heard that day on the radio, listening in the work truck on the way to a manhole somewhere.

Beyond pure exploration, the particulars of our musical exchange offered subliminal windows into our inner lives. If he was sending early ’60s garage rock, I knew all was well in his world. Early in college, when I started sending a lot of Elliot Smith (a singer-songwriter who would go on to commit suicide by stabbing himself in the heart with a steak knife) Dad asked me about my regiment of antidepressants. Then he’d send me something happy, something like The Lovin’ Spoonful.

This November, Dad celebrated his retirement with a major back surgery. I felt guilty for not visiting him in the hospital or calling him enough in the painful days after, so I sent him a YouTube link. It was a John Prine show I’d just discovered, one of his last concerts. “Listen to this when you have a chance,” I wrote. Dad replied immediately: “Listening now.”

When the well of new music dries, Dad and I turn to the classics.

I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve looked out the passenger-side window on I-95 south, heading home from New Haven with my bookbag and acoustic in the back seat, and asked Dad what his favorite Zeppelin track is.

I know what song it is. It’s “The Song Remains the Same,” the live version from Madison Square Garden, 1973, recorded four years before a teenage Dad — on the precipice of so many memories and so many mistakes, full of so much beer and God knows what else — saw the band at the Garden and fireworks rained from the balconies like missiles in a teenage warzone and lit the smoggy arena air in a transient crimson.

I know what song it is. I know the story. I ask Dad so I can hear him tell it again, so I can listen.

#

In memory, the trilogy — Yamaha I, II and III — provides some linearity to the motley collection that would come to consume our basement in the decade that followed “Day Tripper.” A bass without its volume knob, a keyboard bought on sale, a pedal steel that folded into a briefcase, a vintage Yamaha DX7 synthesizer, a dumpster-dived drum kit, an old German accordion still auditioning for heirloom status, a collective heap of unfocused interest.

Guitar, of course, always remained first among equals. I kept playing. I got better. I brought it to college. I poured my heart into the instrument. I played it in clubs, theaters, backyards, and basements. On the nights my first-year dorm felt darkest, I sat at the foot of my bed and plucked the strings in silence.

In the spring of my sophomore year, the night before the musical I was playing in was set to open, my amplifier completely fried. No obvious reason, no sign of life. The next day — still wearing his work clothes — Dad appeared in New Haven with a backup in the trunk of his Jeep.

In the fall of my junior year, I put together a band for a basement show the weekend of Halloween. We played the hits: Michael Jackson, Tears for Fears, The Human League, Talking Heads. Before the set began, I put my phone down on the shelf next to me and hit record. Once the show was over and the video was processed, I sent it to Dad. He called me, thrilled. He wished he could have been there.

In the weeks that followed, I watched the video back dozens of times. I did not care that the camera showed just the paunch of my stomach and the outline of my ass. That night, I played so hard that I snapped a string.

When the pandemic arrived and I returned home in exile, I spent a lot of time in my bedroom. Dad still went to work, but when he got home, he’d sit in his chair in the living room, pick up the guitar, and noodle. Sometimes, I’d head downstairs and play with him, teach him a lick or two. He played not on his old warped Yamaha but on one of mine. After all, we both play right-handed.