Yale faculty discuss the impacts of mass incarceration on health

Almost half of the American population has an immediate family member who was formerly or is currently incarcerated.

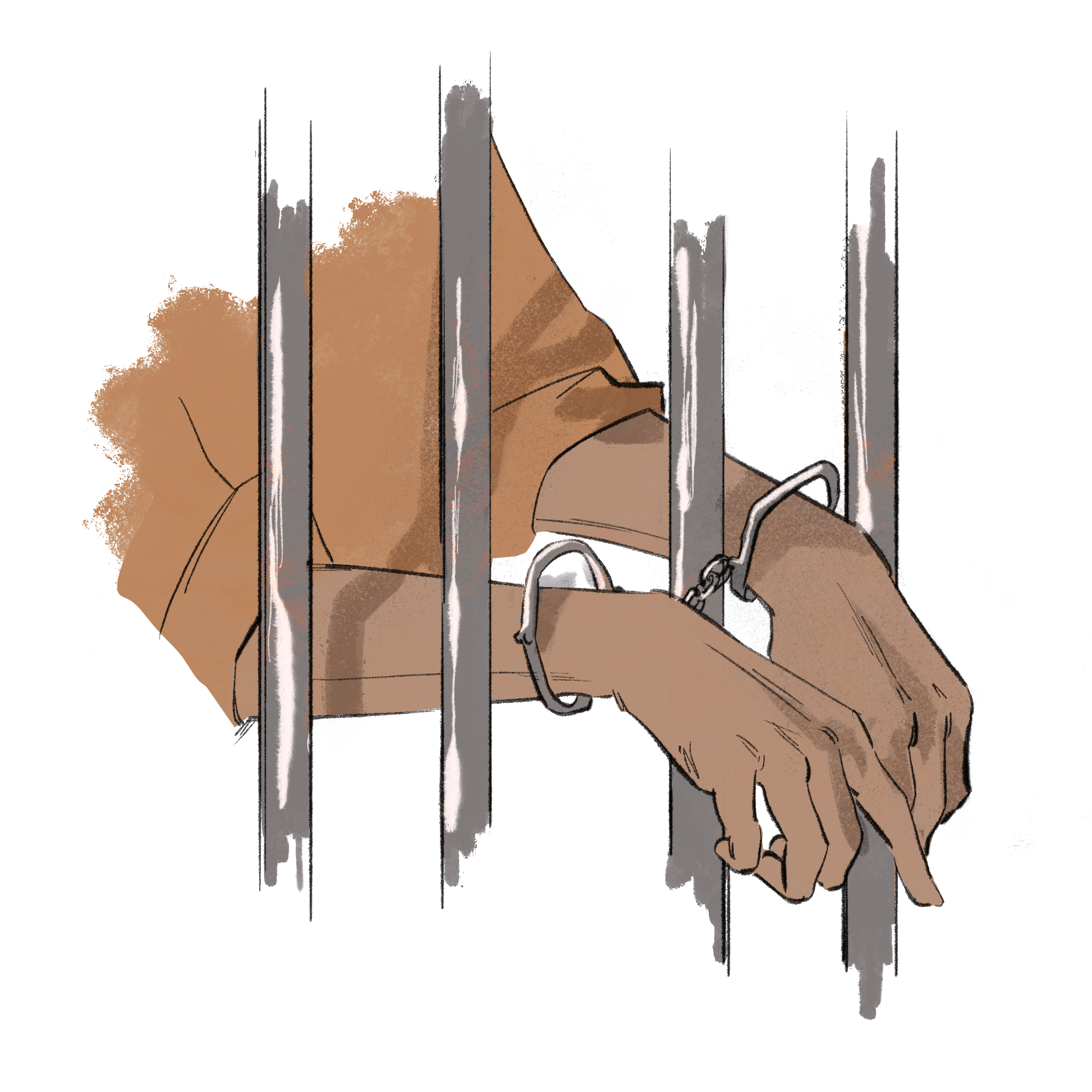

Cecilia Lee

Next year marks the 50th anniversary of the beginning of mass incarceration in the United States. In an episode of the podcast Health & Veritas, Yale physician-professors discussed the health effects of mass incarceration on people imprisoned and their communities.

Yale School of Medicine professor and director of the SEICHE Center for Health and Justice Emily Wang joined fellow Yale physician-professors Howard Forman and Harlan Krumholz for an episode of “Health & Veritas,” a podcast dedicated to highlighting health issues. The SEICHE Center is a collaboration between the medical school and the Law School that focuses on advancing the health and well-being of those impacted by mass incarceration through clinical care, research, education and legal scholarship and advocacy.

“Over the past five decades, we have created a vast system of laws, policies and practices,” Wang said. “Such that we have outpaced all other countries in the world in imprisoning our own citizens. It is a system whose reach also extends to their families and communities. For the past 15 years, I have seen this system’s wide reach grow in clinic. I have seen three generations of a family — grandparents, parents and children — each of whom has been incarcerated, each of whose health has been impacted directly and indirectly by mass incarceration.”

In the podcast, a 2016 study by Wang on hepatitis C treatment in U.S. prisons was used to exemplify the heterogeneity of healthcare behind bars. Hepatitis C is often termed “a hidden epidemic” because at least a majority of those with hepatitis C do not know they are infected, despite it being a leading cause of liver disease, cancer and transplants. At the time of the study, 10 percent of prisoners in the study had hepatitis C in the 41 states whose departments of corrections reported data.

Out of these prisoners, 0.89 percent of these prisoners were receiving treatment. The study ultimately found that despite the release of the DART anti-retroviral therapy, it remained “very costly” and largely unavailable to many state prisoners. Among the state prisons, there was much heterogeneity in who was receiving treatment, with very few prisons systematically delivering treatment, and much less screening for the virus.

“The take-home issue is that there just isn’t the oversight for health care behind bars,” Wang said. “And it only changes when there are court cases involved. And so part of the reason why we’ve really thought about partnerships via law schools is to really think about how culture changes are oftentimes through court cases — legal cases that really push the needle forward.”

The 1976 Supreme Court case Estelle v. Gamble guaranteed the right to health care for incarcerated people. Wang emphasized that this guarantee does not mean that there is equal access, nor is the care necessarily “quality,” or the community standards of care within prison systems adequate. SEICHE’s Health Justice Lab specifically focuses on the largest drivers of mortality among individuals impacted by mass incarceration, such as opioid use disorders, heart disease and cancer.

One of the lab’s grants assesses whether Transitions Clinic, the center’s health care clinic for released individuals, provides care that improves key measures in the opioid treatment cascade after release from jail. Another study evaluates cancer among populations impacted by mass incarceration, with a hypothesis that incarceration contributes to racial and socioeconomic disparities in cancer detection, quality of treatment and mortality.

“At Yale, we have a remarkable group,” Krumholz said. “Focusing on how to help people and their families navigate the challenges of incarceration and then people’s transition from incarceration. Too often this group has been marginalized, and this group is helping us to see them as people, understand their needs and develop programs to help them.”

According to Wang, the COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately impacted not only those who live and work inside America’s prisons and jails, but also the communities surrounding those facilities. In Illinois alone, 16 percent of COVID-19 cases at the beginning of the pandemic were linked to individuals cycling in and out of Cook County Jail, the jail system in Chicago.

Individuals incarcerated and staff are more likely to contract and die from the virus compared to the general public. Wang cited the conditions within the carceral facilities, such as the inability to social distance due to congregate living and overcrowding, and a lack of resources for pandemic preparedness. The SEICHE Center sought to establish the science behind COVID-19 management within correctional systems across the U.S., by partnering with four different correctional systems.

“We have focused lots of energy on making the scientific and ethical argument that the COVID-19 pandemic has shown us what we already know,” Wang said. “That decarceration, the process of depopulating prisons and jails, and investing in safety systems for communities overpoliced and criminalized, is the most urgent public health priority of our time.”

In the podcast, Wang discussed the Medicaid Inmate Exclusion Policy, which prohibits the incarcerated from benefiting from Medicaid. This means that once in a carceral setting, states would suspend Medicaid coverage. However, this creates issues in the transition from incarceration to community due to a lag in the reactivation of Medicaid post-release.

Recently, Medicaid expansion has occurred state by state. In certain states, there are exemption plans which allow Medicaid to kick in thirty days prior to release; in other states, the state waivers are ninety days. In Massachusetts, there are calls to eliminate this policy and continue Medicaid while incarcerated.

According to Wang, the impacts of policies on health care for prisoners have the largest bearing on Black families and poor communities. She found that even though their health outcomes are the worst and are persistent and intergenerational, they remain largely invisible to the scientific and health care community and are significantly understudied.

Wang hopes that this center can be an anchor and catalyst for finding solutions that work in New Haven and across the country. She emphasized the need to engage health systems to “own their responsibility in decarceration” and the need to invest in communities which have been harmed by mass incarceration.

“Our [podcast’s] intention is to illuminate and elevate topics of health and health care concerns that are under-discussed,” Forman said, “A society can be judged by how it treats the least well resourced in society. Whatever penalty we impose on criminals is for others to judge: but it should not come with inhumane treatment.”

The Health & Veritas podcast is released every Thursday on the Yale Insights website published by the School of Management.