“Hard to write off”: Students and experts react to student activists’ complaint filing

Following the Endowment Justice Coalition’s official complaint alleging University fossil fuel investments violate state law, students and experts share their reactions.

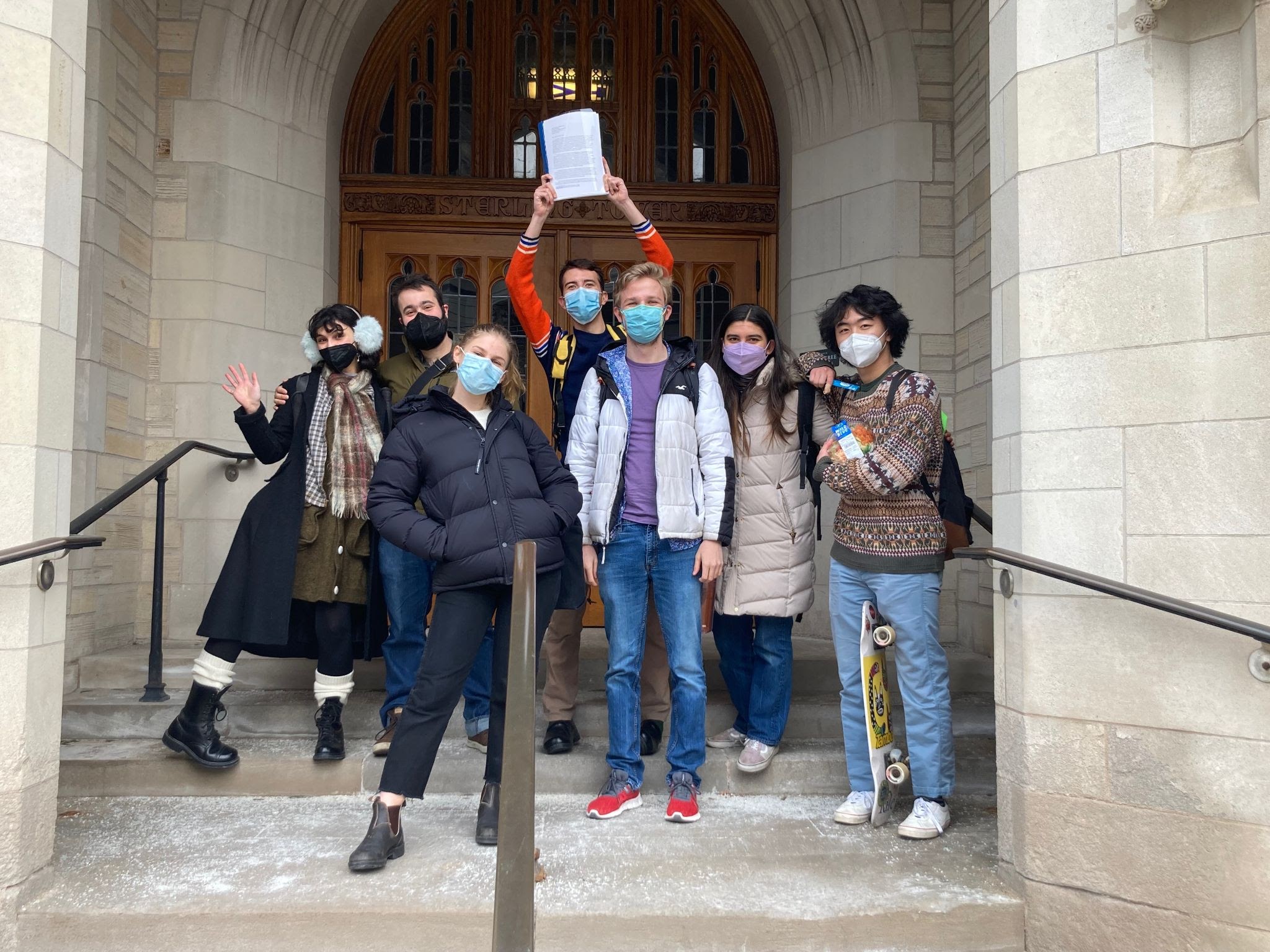

Courtesy of Molly Weiner

On Wednesday, student organizers in Yale’s Endowment Justice Coalition walked to Sheffield-Sterling-Strathcona hall to formally deliver the 83-page complaint they filed earlier that day to University President Peter Salovey’s office.

The EJC, a student group which advocates for the ethical allocation of the University’s endowment, has previously staged protests, rallies and an occupation of Cross Campus to call for divestment from fossil fuels on ethical grounds. But on Wednesday, students filed a complaint to Connecticut Attorney General William Tong alleging that the University’s continued investment in the fossil fuel industry violates state law. Now, people on campus and beyond — including student activists, University officials and endowment experts — are looking ahead to the potential impacts of the complaint.

“It’s been incredibly exciting to see media coverage rolling in,” EJC organizer Josie Steuer Ingall ’24 told the News. “I think this strategy really has the potential to reshape institutional investing in a powerful way, but that can only happen if people know about it. I’m really glad it seems like they will — they do.”

The EJC constructed its complaint in partnership with student activists at Princeton, Stanford, Vanderbilt and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Students at each of the universities filed a simultaneous complaint to their respective state attorney generals. The activists filed their complaints at 9 a.m. ET Wednesday, and they immediately made national headlines.

The Yale complaint alleges that the Yale Corporation — the University’s highest governing body — violates a provision of the 2009 Uniform Prudent Management of Institutional Funds which stipulates that tax-exempt nonprofit entities like universities must invest with charitable interests in mind. When students at Harvard and Cornell filed similar complaints, their respective universities divested from fossil fuels within six months.

EJC organizer Molly Weiner ’25 emphasized to the News that the goal of the complaint is not only to spur Yale toward divestment but also to set a precedent for the legality of nonprofit organizations investing in fossil fuels in general.

“There’s so many ways to pressure the University to divest and we chose this one,” Weiner said. “The most thrilling thing would be not for Yale to panic-divest, but for the attorney general to actually open an investigation. We’re doing this not just because of what could happen with Yale, but in the entire state of Connecticut.”

When asked for comment, University spokesperson Karen Peart directed the News to previous steps Yale has taken in response to call for divestment. These steps include setting new carbon reduction targets, establishing new principles to guide fossil fuel investment and funding the Planetary Solutions Project to engage in climate change research.

But Yale, unlike peer institutions such as Harvard and Cornell, has made no plan to completely divest from fossil fuels, causing EJC to turn to the judicial process.

The next step, organizers told the News, is encouraging students who agree with the EJC’s stance on divestment to sign on to the complaint. Since it went public this morning, Weiner said, hundreds of people have already added their names.

Katie Schlick ’22, co-executive chair of the Yale Student Environmental Coalition, was one of the students who added their names to the complaint today, voicing her support for Tong opening an investigation into the University’s fossil fuel holdings.

“One of the main things that I felt today was just pride in seeing how much research and care and thought was put into the filing,” Schlick said. “It’s just very cool to see that a group of students has been working so diligently, coming at this from every single angle. They sat on the football field. They’ve sat in meetings with the leadership of this institution. And now they’re also bringing it to the courtroom, in a way, and that’s just really exciting.”

Schlick also emphasized the stakes of the complaint, pointing to Yale’s capacity to effect change due to the size of its endowment and its ability to set a precedent for others.

Steuer Ingall told the News that the outpouring of student support did not come as a surprise.

“I was optimistic,” Steuer Ingall said. “I think the research we’ve accumulated is pretty damning, and I knew that if we had a strong rollout with a consistent social media presence, we were going to pretty immediately find it possible to demonstrate consensus among the student body.”

Weiner added that she hoped other universities would take similar action, pointing to the guide that Divest Harvard compiled to aid students in filing a similar complaint against their universities.

But Charles Skorina, an expert in university endowments, questioned the efficacy that the complaint will have in encouraging Yale to divest.

“I think that this suit filing this morning, it may draw attention to their activism,” Skorina said. “But as a practical tool, it’s not effective. It may be for publicity.”

Skorina explained that when university endowments partner with investment managers, such as private equity programs and hedge funds, they must sign contracts that ensure the partnership lasts for a specified period of time. These contracts are legally binding and prevent endowment managers from retracting their funds in the short-term. Immediate divestment from fossil fuels would lead to massive losses resulting from violating previously established contracts, Skorina said.

While schools like Harvard have announced divestment from fossil fuels, Skorina said, it will take “years” for them to fully divest.

Skorina added that while student organizers could still protest Yale’s investments, he would be surprised if anything came of the decision to file a complaint, adding that he “didn’t follow the logic.”

But EJC organizers were undaunted by Skorina’s concerns.

“I think [Yale knows] that these investments are indefensible on moral grounds and that they’re probably indefensible on legal grounds as well,” organizer Moses Goren ’23 told the News. “I would be very scared if I were them.”

Weiner pointed to the extensive research that the EJC has conducted into the University’s ties to the fossil fuel industry, as well as to the aid students received from attorneys in the Climate Defense Project, as evidence of the complaint’s legitimacy.

Support for the EJC’s effort extends beyond the student body, Weiner added, pointing to the environmentalists and Yale faculty members that have already signed onto the complaint.

“It’s not just students,” Weiner said. “It’s dozens of faculty, prominent alumni, elected officials, New Haven alders. They can’t be like, ‘Oh, you know, it’s just kids causing trouble.’ We have so much entrenched institutional support that it’s really hard to write off.”

Yale announced its guiding principles for investment in the fossil fuel industry in April 2021.

Correction, Feb. 18: A previous version of this article said that Schlick was the co-president of the Yale Student Environmental Coalition. In fact, Schlick is the co-executive chair. The article has been updated to reflect this.