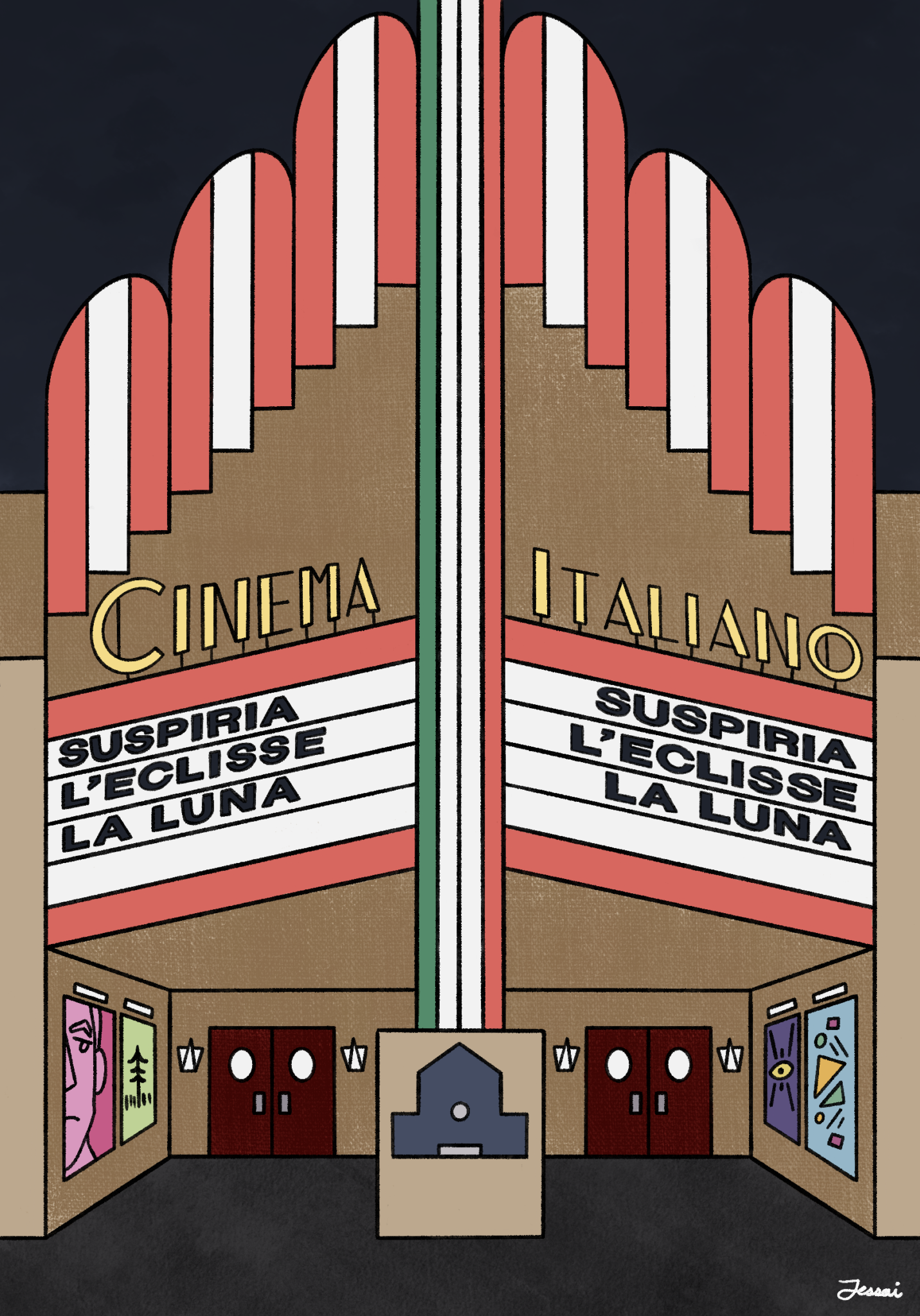

Jessai Flores

You’ve taken your first-level language course at Yale, and you wanted to have some fun with it. So, Italian—the beautiful language of rhythmic resonance — it is. You are so hyped about it, and you greet your friends with “Ciao!” and wave them goodbye with “Arrivederci!” You are new to this, so you still have the excitement of beginning to learn a new language and the motivation to review the topics covered in the course by yourself — even during the winter break. The miserable Duolingo days that were — primarily — motivated by an Italian summer fling are finally over; you are a professional at the game now. It’s business, as usual. And you are a cinephile, just like me. Well, what do you do? You go into Italian film — ah, although still with the subtitles unfortunately!

I would say this was how my journey into fine Italian cinema began over the winter break. Below is an anthology of my favorites among the ones I’ve seen. Enjoy, and please shoot me an email if you have already seen or are planning to watch them, so we can chat!

***

“Ladri di Biciclette” — “Bicycle Thieves” — Vittorio De Sica, 1948:

“Forget everything: we’ll get drunk!”

Translated to English as “The Bicycle Thieves,” Vittorio De Sica’s 1948 masterpiece set a milestone in the Italian neorealist movement. The Movement was developed against the unrealistic Hollywood gloss, marked in the film itself by the ironic presence of a Rita Hayworth poster and “white telephone”—superficial entertainments which ignored the realities of an Italy invaded during WWII. Given that the Italian film industry was in ruin and the directors were practically too broke to hire professionals, shooting simpler films about and with ordinary people was a natural consequence. Thus, the movement’s aim was to focus on everyday people, follow their believable stories and problems, and chronicle the political and economic consequences of post-WWII Italy. The entire film’s cast consisted of non-professionals—Antonio Ricci (Lamberto Maggiorani) in the role of a poor man finally given the job opportunity of delivering and hanging movie posters, yet with only one condition: he must do so on a bike—which he doesn’t have. Although his smart wife (Lianella Carell) quickly figures out a way — “We don’t need sheets to sleep” — to find money among all the challenges of poverty that the family already has to deal with and redeem Ricci’s bike, Ricci and his little son Bruno (Enzo Staiola) are destined to hop on a desperate odyssey to get the bike back—stolen on the first day of work. Their journey consequently reveals a series of scenes unveiling the poverty of Rome, which were left out from the government’s preferred way of representation in the media. While the film is heavily filled with crowds talking, accusing and shouting at Ricci and his little boy which may feel psychologically unbearable from time to time, it is also constantly cut by De Sica’s witty brushes of humor. For example, De Sica teases us, the audience, by delaying the time of Ricci’s return in one scene and making us anticipate that his bike will be stolen by then — as indicated by the film’s title — yet, when he returns, the bike is still there. Two quotes by Ricci, “Why should I kill myself worrying when I’ll end up dead?” and “There’s a cure for everything except death” when he thinks he has lost his son, give a sneak peak to the working man’s psyche residing in Italy at the time—his mind constantly occupied with struggles to earn a living and a search for justice in a society which doesn’t seem to comprehend or empathize with him. “Bicycle Thieves” is an atmospheric film with its documentary-like shots in black and white, and I’d recommend it to anyone who’d like to have a glimpse at everyday life of then-Italy, along with many similar scenes in other corners of the world at the time.

“La Dolce Vita” — “The Sweet Life” — Federico Fellini, 1960:

“Even the most miserable life is better than a sheltered existence in an organized society where everything is calculated and perfected.”

“La Dolce Vita” is dolce only in the first blush, when it initially paints a dizzying era in the “II Boom,” in other words, “The Italian economic miracle” — “il boom economico” — a term used by historians and mass media to describe the prolonged period of growth in the Italian economy post-WWII to the late 1960s, and particularly in between 1958-1963. Fellini’s classic met with the audiences in 1960 precisely during the middle of il boom, and inevitably depicted familiar scenes from the carefree world of the era. It follows a handsome and weary paparazzo, Marcello (Marcello Rubini), and his somewhat dull days within the elite circles of Rome: bodies wandering aimlessly without the constrictions of budget allocation, strong emotions or connections, only aiming to live a life of pleasure by liberating their libido with high art, poetry, aesthetics and theatre. As artificial laughters, foolish jokes about money, small exchanges in English — a universal signal of an elite circle, I suppose — implications of sex promissories, cigarette smoke and alcohol fill the grotesquely decorated scenes, the mutual selfishness and loneliness of the film’s characters ironically end up making Marcello’s quest of climbing the social ladder quite circular. It’s the usual human lust and greed, only without the usual preoccupations with hiding it. Film characters seem to mock each other with a similar taste of humor, boredom and playfulness while embracing their own absurdism — because they surely can afford to do so — and are only restricted by the boundaries of film-making surrounding sex back then. Yet, they still manage to look as if they’ve just come out of the next generation of films like that of Stanley Kubrick’s 1999 “Eyes Wide Shut” which featured an orgy—and this absence of explicit sexuality, in my opinion, only crescondoes the strength of their acting.

The film doesn’t forget to offer a magnifying glass to Marcello’s life either. As he rushes from one place to another amidst aggressive celebrities and selfish paparazzi like himself, Marcello ironically replicates the actions of his father, who always used to leave young Marcello and his family to seek the “dolce vita” in other towns, with concerns of boredom — the thing that ages us the most, according to him — with his own suicidal girlfriend/fiance Emma (Yvonne Furneaux) when he leaves her alone with whimsical thoughts, despair and jealousy in order to return to his regular shift of womanizing and night owling. Is Marcello a damned soul, who is trapped in Rome’s reckless atmosphere of luxury, which prevents him from seeking his true ideals of writing a novel? Is he not free to walk away? Does he not have willpower? No one cares, I’d argue—not even Marcello himself after one point—when he eventually joins the circle of ridicule and merely ticks away the moments that make up his dull days and nights.

“Speed can be fun, productive and powerful, and we would be poorer without it,” Carl Honoré, a Canadian journalist, argues in his international best-selling book “In Praise of Slow” about the Slow Movement—which advocates a cultural shift to slow down life’s pace. “What the world needs, and what the slow movement offers, is a middle path, a recipe for marrying ‘la dolce vita’ with the dynamism of the information age. The secret is balance: instead of doing everything faster, do everything at the right speed. Sometimes fast. Sometimes slow. Sometimes in between.” It’d be a good quote to keep in mind while watching the film, which I plan to do the next time I see it. Finally, I have to admit that seeing “La Dolce Vita” right after “Ladri di Biciclette” is quite a shocking experience, which is exactly why I’d recommend anyone who’s interested to precisely follow this order if they want to further immerse themselves in the dazzling cosmos of film-making.

“La Vita è Bella” — “Life is Beautiful” — Roberto Benigni, 1997:

“This is a simple story, but not an easy one to tell. Like a fable, there is sorrow, and like a fable, it is full of wonder and happiness.”

Likewise, this is not an easy film to write a review about—especially when you can only give it a paragraph—you have to see the movie and its universal beauty itself! However, Roger Ebert, who was an American film critic for the Chicago Sun-Times from 1967 until his death in 2013, generously provides us a framework to structurally split the film. According to Ebert, there are two parts in the movie: the first is pure comedy, to which we are introduced through the Charlie Chaplin-esque character Guido (Roberto Benigni himself), an adventurous and sociable hotel waiter in Italy in the 1930s, and the story of how he falls in love with the beautiful Dora (Nicoletta Braschi, Benigni’s real-life wife), overcomes his Fascist town clerk rival and eventually marries her. The second part reveals that Guido’s humor is not light-headed at all unlike how it seems so in the first half; several years pass, Guido and Dora have an adorable 5-year-old son Giosuè (Giorgio Cantarini), and we slowly begin to worry about this sweet family’s future when we finally learn that Guido is Jewish, and he, along with his son, are in danger in a town controlled by the Fascists. Eventually, Guido and Giosuè are loaded into a train to be shipped to a death camp, and despite the fact that she’s not Jewish, Dora hops along to share the same fate with her son and husband. The beautiful wisdom behind Guido’s witticism finally is revealed when he constructs an elaborate fiction to comfort his son; the Nazi concentration camp is a game, and one must not ask for food, cry, or want to return back home even when the conditions are the most unbearable, if one wants to gather 1,000 points to win the big prize: a real tank — an image that has been adorning Giosuè’s dreams for a long while. I don’t want to give a spoiler, but the film’s ending manages to synergize its two separate parts when it leaves you with smiles through tears. And, years later after its initial release, “La Vita è Bella” still reminds us that it’s possible for us to hope for the future and do our best to rescue what we have in our hands today—even in the instances when our dreams are completely wrecked.

“Nuovo Cinema Paradiso” — “New Paradise Cinema” — Giuseppe Tornatore, 1988:

“Life isn’t like in the movies. Life… is much harder.”

I was destined to see this film when my dad, a big fan of Ennio Morricone, sent me Morricone’s 1991 album “Cinema Paradiso,” composed exclusively for the movie carrying the same name. “These are by ‘il maestro’,” my dad jokingly announced in Italian, when he introduced me to Morricone—a unique figure in the history of film music, a European who was born in Rome and came to dominate the scoring of Western films in the 1960s — including “The Good, the Bad and The Ugly” (1966), “Once Upon a Time in the West” (1966) — along with scoring for the later action, thriller and western classics by Quentin Tarantino—such as “Kill Bill,” “Inglourious Basterds,” “Django Unchained” and “The Hateful Eight.”

The names of the pieces in the album capture the unforgettable moments of the film perfectly. As we observe the protagonist Salvatore (Salvatore Cascio) — affectionately known as “Toto,” a little boy living in a WWII-torn Sicilian village — grow before our eyes, we are accompanied by “Maturity” and “Childhood and Manhood.” And, of course, “Love Theme” and “While Thinking About Her Again” can only go for Toto’s first love Elena (Agnese Nano), the daughter of a wealthy banker. Alfredo (Phillippe Noiret), the middle-aged projectionist of the town, however, is always in picture and occupies a crucial place in Toto’s life and the movie itself: from providing the warmth and care that Toto’s father (who died in the war) could not, to making possible the moment when Toto first acquires his cinephilia, replaces Alfredo, makes the decision to go to Rome, and finally becomes a famous director.

While the film also deals with broader concepts like nostalgia, confrontation and the sentimental journey back to the homeland, and the immigrant’s dilemma of constantly remaining somewhere in between, it also introduces us to the regular audience of the cinema — a microcosmic representative of Sicilian inhabitants of the day, some smoke, some drink, some prank, some seal romances, and all complain about the censorship of kissing scenes in the movies.

Tornatore’s masterpiece won the 1989 foreign-language film Oscar and, to this day, remains as the 18th most successful foreign-language film in America. “New Paradise Cinema” also led the way to the rise of streamlined foreign-language films, along with other foreign-language Oscars prior to 2000. Thus, perhaps we can say that the film’s emphasis on the power of dreams didn’t end up merely being symbolic, as it continues to inspire artists and filmmakers across the globe, reminding them that they and their works too can travel to the far corners of the world, just as Toto did himself.

***

I can already see you rolling your eyes: I know, I know, they are basically classical movies that have already made it to “must see 100 movies of all times” on IMDb and stuff! And yes, I haven’t seen any of them until this historical winter break — I guess a big step for me, a small step for humankind. But, okay, here is my defense: we have this saying in Turkish, which translates into something like “let it be late rather than difficult” — similar to “better late than never” in English. Well, I guess I’ve never appreciated this adage enough until this day 🙂 Anyways, thank you for bearing with my stream of consciousness on paper, and I shall soon share my novel Italian film discoveries with you! Until next time, arrivederci!