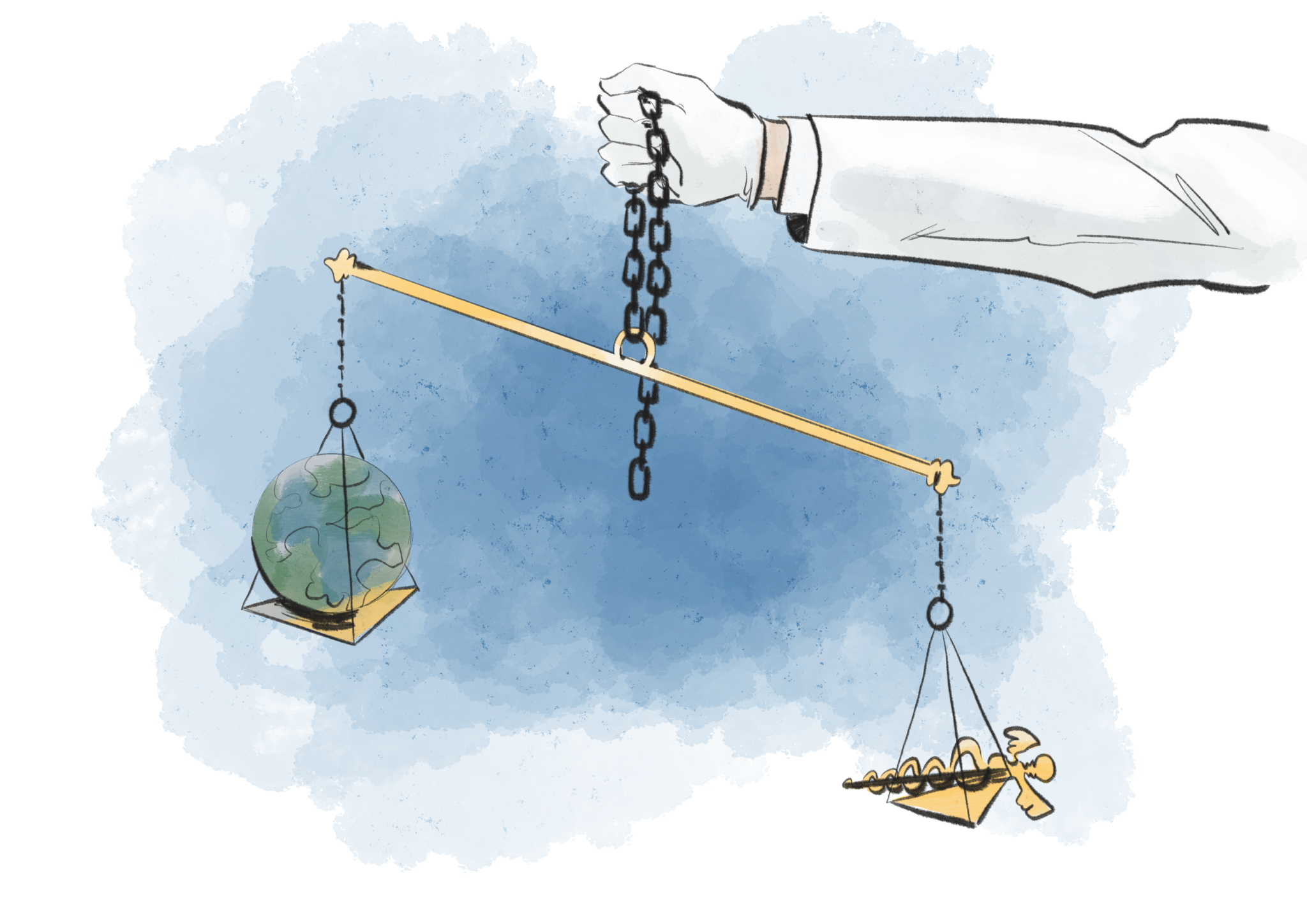

Cecilia Lee Illustration.

One of the academic highlights in my graduate studies at Yale was not in my home program, the Yale School of Public Health, but at the Yale Divinity School. YSPH allows students to enroll in courses throughout Yale with several caveats, one of which is that the course is tangentially related to public health. While pursuing the Yale course catalog, I stumbled upon a YDS course titled Theology and Medicine. The title was intriguing enough, so I decided to give it a shot.

The course tackled topics ranging from Theology and medicine in the ancient world to burnout among physicians in the present. All of the topics were interesting and many were relevant to my career goals and interests. As a public health professional, I study morbidity and mortality, prevalence and incidence of disease — all words that the U.S. public is now familiar with, thanks to COVID-19 – but none of my YSPH classes have broached the humanistic component of death. I can describe the risk individuals have for disease, or the impact an illness has on life expectancy, but my public health training has not taught me what this means for the individual, or how to counsel a community for the death of loved ones. The concept of death, dying, and rituals that are important to people in their last hours never made it onto the syllabus of Introduction to Epidemiology or Social Justice and Health Equity. Perhaps these questions were outside the scope of the classes, but are they outside the scope of the U.S. Healthcare System or the recommendations that public health professionals make? The perspective I gained from thinking about death and its implications has impacted how I view public health and clinical recommendations for the better.

One night at dinner I was exploring these ideas with my wife. For reference, my wife is a nurse with years of experience working in both the Emergency Department and Intensive Care Unit. Because of her vocation, she has seen both the successes of modern medicine and its limitations. I asked her “what facilitates a good death.” She sat back in her chair and said, we —healthcare providers and public health professionals — can’t facilitate a good death unless the patient helps us do so. As we talked, the conversation developed into a discussion on preparedness for death. Death is a natural phenomena that we all experience, and having a healthy understanding of our own mortality allows us to have agency over death, thereby facilitating “dying well.”

In the first chapter of Being Mortal, Atul Gawande discusses death as being a trap door that takes the floor out from under one’s feet. Similarly, Dr. Lydia S. Dugdale, author of Lost Art of Dying: Reviving Forgotten Wisdom, discusses the abrupt contemplation of death in her conversation with a patient she had seen for years; “the prospect of death had forced her to reflect on the meaning of life.”

The existential question of mortality points to a duality that is often perceived as a dichotomy. However, I believe that considering death and talking about it — in healthy moderation — facilitates the capacity to live a good life. For the recent widow or widower, conversations on death give closure; for the medical proxy, conversations about end-of-life wishes provide clarity on what decisions the ill or dying loved one would want. Discussions on death give freedom to not only live and die, but to take ownership over death, wherever possible.

Returning to the answer my wife gave, I must agree. Medical providers and public health professionals are not able to facilitate a good death because it is by-and-large outside their purview; however they can assist and catalyze the starting of the conversation on death. This is a topic I think individuals in the health field should wrestle with, and I would go so far as to say that course work at YSPH should touch on it too. Since public health is a discipline that brings health communication to people and to communities, should we not also discuss health strategies to cope with and prepare for death? Perhaps this is an area of growth for the public health and healthcare work-force, and an area that those in the scientific community can learn from those in the humanities. Beautifully put by Dugdale, in bridging the conversational gap between life and death, the provider “cease[s] to be a ‘provider’— what good or service can [they] possibly provide? Instead, [they] again become a physician, a healer who aspires to see her patients flourish.

Joseph Williams is a first-year MPH candidate in the Yale School of Public Health. His column ‘Contemplating health’ runs on alternate Thursdays.