Sophie Henry

“I once had a girl

Or should I say

She once had me

She showed me her room

Isn’t it good

Norwegian wood”

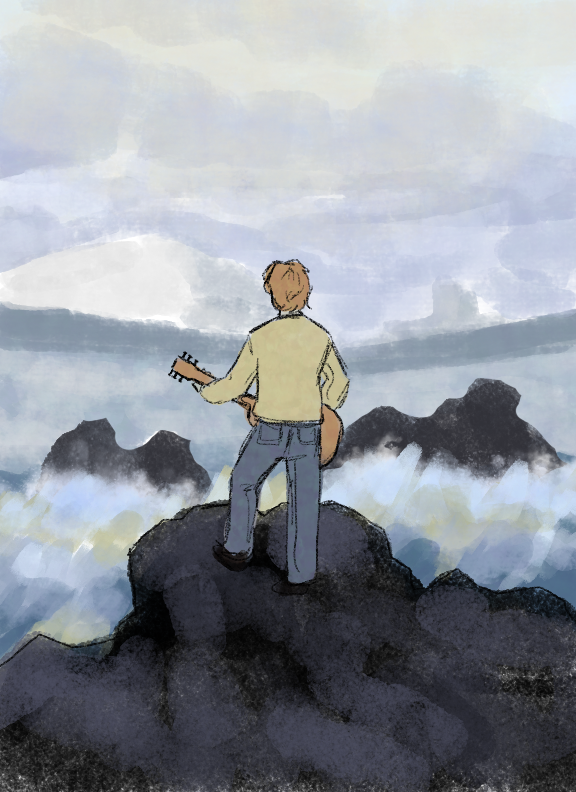

I had always loved the Beatles and vibed with “Norwegian Wood” when I encountered Haruki Murakami’s bestselling novel of 1987 by the same title. The book propelled me to contemplate the deeper meanings of every song — of course, starting from “Norwegian Wood.” I may be biased, given that the novel “Norwegian Wood” is full of artists, films and literature that I immediately got hyped for after coming across them, like Simon & Garfunkel’s unforgettable “The Graduate” tracks and the guitar of Reiko — a middle-aged musician who’s recovering from a breakdown — gently weeping the timeless Beatles songs to perhaps the most iconic psychedelic rock bands of the era, the Doors and Cream.

In fact, “Norwegian Wood,” begins with the 37-year-old narrator Toru Watanabe, who hears the song “Norwegian Wood” as he flies across the North Sea and is carried back to his youth in Japan in the late ’60s. Amid the era’s buzzing student protests, the tension between the traditional collectivism of the Japanese culture and the emergence of American individualism due to the influence of Westernization and Tokyo’s streets filled with alcohol, dance and the peak of sexual revolution, Toru seeks out his personal identity and narrates a series of delicate love stories.

The first one is with Naoko, the ex-girlfriend of his childhood best friend Kizuki, who commits suicide. Don’t worry! Toru is also aware that this sounds awkward at first blush, as he reflects: “My warmth was not what [Naoko] needed, but the warmth of someone else. I felt almost guilty being me.” Yet, Naoko and Toru both happen to still be suffering from the unprecedented loss of Kizuki. As loneliness vibrates the pages, Naoko and Toru offer each other company and warmth in Tokyo, as Toru — and probably Naoko as well, although we can never tell for sure because we’re confined to Toru’s narration and its limited perspective — realizes both happen to have flown away to college as a way to escape from their past: “When I saw her room, I realized that, like me, she had wanted to go away to college and begin a new life far from anyone she knew.”

However, the mental well-being of Naoko — who is perhaps the most fragile and sympathetic character I’ve ever come across — gradually decreases, and she is forced to quit college and receive therapy in a sanitarium. As he finds a job at a record store to minimize his emptiness inside, reduces his social interactions, reads books and listens to music in solitude, Toru crosses paths with the pretty, witty and intelligent Midori, who is full of life and energy. As Toru describes: “Her eyes moved like an independent organism with joy, laughter, anger, amazement and despair. I hadn’t seen a face so vivid and expressive in ages, and I enjoyed watching it live and move.”

While the novel consists mainly of scenes of Toru repeating the same activities over and over again, like going to school, working at the record store and paying frequent visits to the nightclubs — there is something incredibly human and real about “Norwegian Wood,” which makes it a piece of literature that everyone can relate to. Reading “Norwegian Wood” is facing revelations entangled with your own life that you weren’t even aware of. One of the ways that “Norwegian Wood” touched me the most was its setting in the past, as I pondered not merely our own individual conceptions of time, but also the overarching questions of how to find one’s identity, live life and cope with the loss of loved ones. Toru’s struggle is not merely idyllic nostalgia, but rather a desperate attempt to preserve the past: “I straightened up and looked out of the window at the dark clouds hanging over the North Sea, thinking of all I had lost in the course of my life: times gone forever, friends who had died or disappeared, feelings I would never know again.” That’s precisely why Toru turns to literature and writes this book. It is “to think. To understand. It just happens to be the way I’m made. I have to write things down to feel I fully comprehend them.”

The motif of music was definitely one of my favorite parts of the book. Apart from the mere pleasure of coming across a beloved artist, the novel also propelled me to rediscover my favorite songs’ lyrics, as every bit of literature and music seemed to be there purposefully. To begin with, the lyrics of “Norwegian Wood” reflect the situation of Toru with both women in his life, Naoko and Midori, perfectly: “I once had a girl/ Or should I say/ She once had me.” Despite being the protagonist, the interactions of Toru with Naoko and Midori somewhat carry more importance than Toru’s character, as he swings between Eros, with the pure and innocent love of Naoko, and Thanatos, with the sexually liberated Midori, who loves going to theater to see pornography and particularly enjoys the most offensive scenes. “When I awoke, I was alone, this bird had flown.” Believe me, this line isn’t a coincidence either. Why? I won’t spoil you and I’ll let you discover on your own!

The recurring themes of art, literature and music don’t only draw allegorical lines with the situations that characters are in, but also help them to describe their emotional states and convey thoughts that otherwise they wouldn’t have. As Midori explains: “‘I don’t know, I feel like this isn’t the real world. The people, the scene: they just don’t seem real to me.’ Midori rested an elbow on the bar and looked at me. ‘There was something like that in a Jim Morrison song, I’m pretty sure.’ ‘People are strange when you’re a stranger.’ ‘Peace,’ said Midori. ‘Peace,’ I said.’” Or, as Toru chats with Midori’s ill father about Euripides, he emphasizes: “There’s almost always a deus ex machina in Euripides, and that’s where critical opinion divides over him. “But think about it — what if there were a deus ex machina in real life? Everything would be so easy! If you felt stuck or trapped, some god would swing down from up there and solve all your problems. What could be easier than that?”— unlike how nothing in his life is really easy for Toru. Transferring from being a teenager to adulthood, learning to cope with loss, experiencing love and sex are all parts of growing up, and the roles of music, film, art and literature all combine to help him establish an identity for himself throughout the novel. I thus genuinely don’t think Murakami was throwing the popular culture of the ’60s throughout the various parts of the book randomly: they all had their unique places as a way to dig deeper into the inner worlds of the characters unconfined by the inevitably biased narration of Toru.

Perhaps one of the ways that Toru was so humane to me was because both of us happened to be college students around the same age. Perhaps he made me feel less awkward about my own quirks in the moments I realized how weird I may seem from an outsider’s perspective. Yet, I somehow mirrored Toru’s frequent no-contextedness terrifically, in the moments like headbanging to various rebellious songs from the ’60s while reading Orhan Pamuk’s “İstanbul” under a peaceful, New England fall-colored tree.

As I contemplate these lines, I take a sip from the cheapest good-quality wine I could find earlier in the day, close my eyes and think of what it means to be conscious of one’s own life — past, present and future— in a suite gently filled with the fume of vanilla and strawberry incense sticks and delicate plants and flowers. Meanwhile, Abigail sings and plays “The House of the Rising Sun” and “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” on the most beautiful guitar I’ve ever seen. It belongs to her grandmother, whose Woodstock adventures I listened to only a few weeks ago when I met her. As her grandfather funnily inquires “Who killed the Kennedys?” when the Rolling Stones come up in the conversation, I harken back to times when Abigail and I listened to “Sympathy for the Devil” together while dancing barefoot on streets or running hand-in-hand by the diamond sea at Beach Street under the starry midnight sky. It feels funny, the fact that we are all so obsessed with being special and immortal, or leaving something behind before we leave this world. And it is especially funny when one considers how arbitrary the boundaries between people are, as the snapshots from a person’s life can very easily intermingle with each other and those of novel characters. Yet, I also have this strong urge to write like Toru. I feel that if I don’t write them down, I’ll never comprehend what is really happening in my life and the moments will begin to fly away from me. But, at the same time, I guess any memory can be immortal on paper when one adds a little bit of music.

Writing about songs entangles literature and music and allows a single piece to harbor many microcosmic life stories through various ways of narration. Just how we immediately feel close to someone when we realize that, even though in different contexts, both of us went through similar emotions; literature, music, film and other kinds of art align different human lives in unimaginable ways and offer consolation amid the cold breath of existential loneliness. Each moment in Toru’s Norwegian Wood of memory speaks to our own life cycles, yet in an idiosyncratic way for every single one of us. Perhaps you may object, arguing that consolation doesn’t always offer a solution. But, in the grand scheme of time, memory and life, is finding a pragmatic solution really more important than encapsulating time via the means of art and understanding and accepting incidents in our lives? And, despite everything, isn’t it really good: Norwegian Wood?