University ramps up testing requirements amid COVID-19 spike

Yale College has upped student testing requirements in response to 98 positive COVID-19 tests on campus between Nov. 26 and Dec. 3.

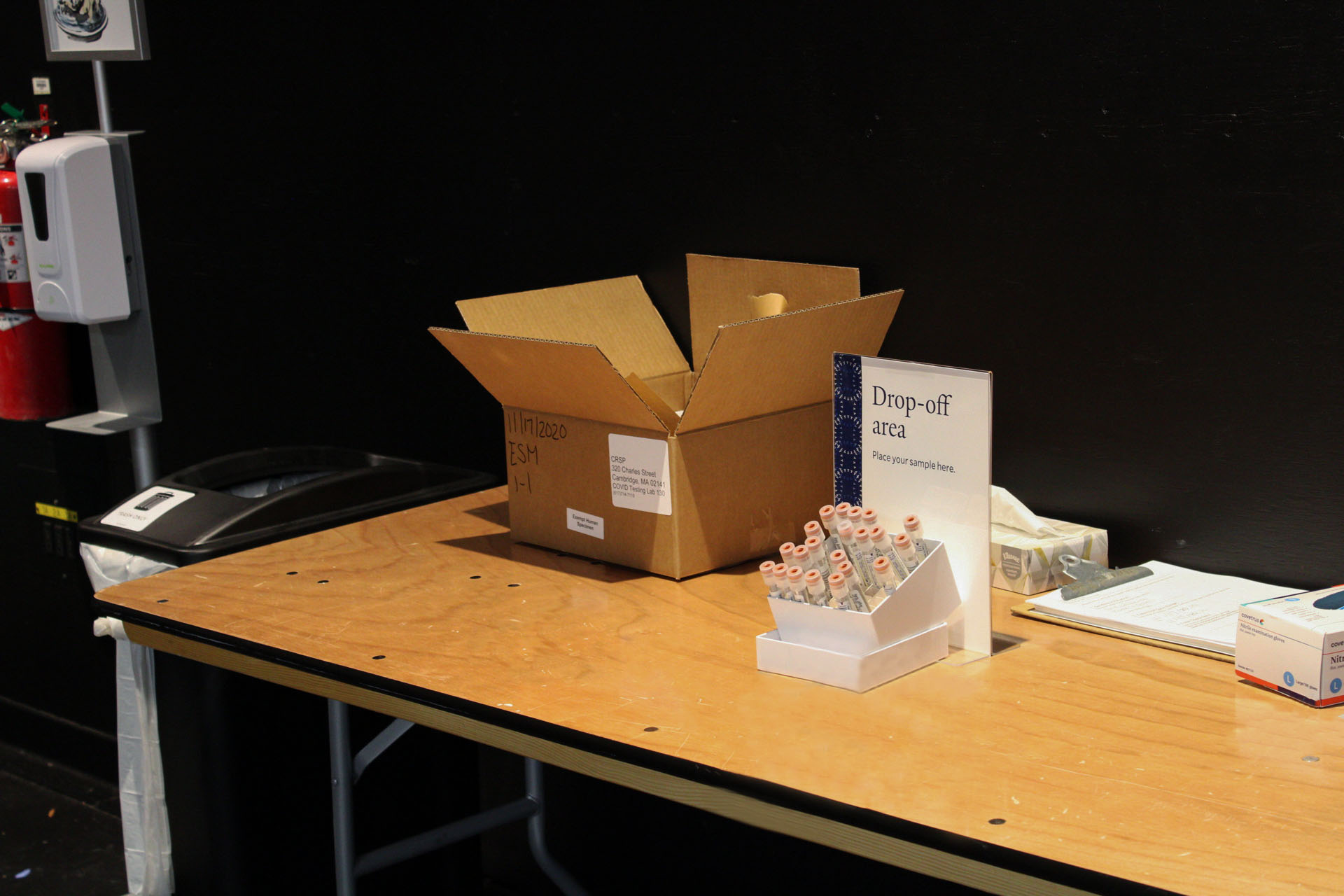

Yasmine Halmane, Contributing Photographer

COVID-19 cases on campus have risen sharply over the past week, triggering a change in alert level from green to yellow and sparking concern for some about the efficacy of Yale’s public health protocols. The University has responded to the uptick by mandating twice-weekly testing for undergraduates until the end of the fall semester.

According to the Yale COVID-19 data dashboard, the University has logged 98 positive tests in the seven-day period ending on Dec. 3. The current spike represents the first major jump in cases this fall in a semester characterized by consistently low positivity rates and a return to semi-normal campus operations. Currently, there is little risk that large swaths of the University will be quarantined as they were last year, according to Richard Martinello, medical director of infection prevention at Yale New Haven Health and member of the public health committee which advises University COVID-19 Coordinator Stephanie Spangler. But Howard Forman, professor of radiology and biomedical imaging, public health, management and economics, noted the rise in cases could affect final exams, with some students taking them online or postponing the assessments altogether due to illness.

“The number of COVID-19 cases and the rate of transmission have risen sharply on campus, just as they have in New Haven and nationally during this period after holiday travel,” Dean of Student Affairs Melanie Boyd wrote in a Sunday evening email to the student body.

Boyd added that students will be assigned testing schedules to help testing centers balance the influx of additional appointments. The schedules will require students to complete their tests either on Mondays and Thursdays or Tuesdays and Fridays. On Dec. 8, students will be able to view their assigned testing schedules on Yale Hub.

On Dec. 1, undergraduate students living on campus were asked to up their weekly COVID-19 testing requirement from one test to two for the week following Thanksgiving break. The new policy will extend this testing schedule until the end of the semester.

Yale College Council president Bayan Galal ’23 told the News that she views the switch to twice-a-week testing as a “new and important step in the right direction.”

“The more frequently you test, the earlier you would be able to identify somebody who may be contagious with COVID, and then make sure that they’re appropriately isolated,” Martinello said. “By increasing the frequency from every seven to every three days, that increases the likelihood that if somebody is sick and contagious, you’ll find them sooner, before they have as much chance to expose somebody else.”

Galal noted that the YCC has coordinated with the University’s various COVID-19 committees throughout the semester to provide a student perspective on public health guidelines and pandemic-related developments.

“It’s incredibly important that students, faculty, and administrators alike all work to ensure a safe campus as cases rise,” Galal wrote in a statement to the News. “It’s also critical that we consider our impact on New Haven residents as we interact with the community at large.”

Boyd’s email instructed students to receive booster shots, obtain a symptomatic test if they experience COVID-19 symptoms and wear masks whenever they are outside of their suites. Boyd also requested that students avoid unnecessary travel, adding that students should ideally stay in New Haven for the remainder of the semester.

On Dec. 1, when Spangler announced a shift in alert level from green to yellow — connoting low to moderate risk — Yale’s COVID-19 data dashboard reflected 48 recorded cases in the seven-day period ending Nov. 29. The most recent data, showing 98 cases, reflects a 104 percent increase in the seven-day total since Nov. 29.

The University’s COVID-19 screening program began detecting more positive cases following November recess. Many students used the weeklong break to leave campus, travel across the state and country and spend time over the Thanksgiving holiday with family and friends, all of which increase the likelihood of COVID-19 spread.

Two positive tests were recorded on Nov. 27 — the Saturday following Thanksgiving — and that number rose as students returned to campus over the weekend, jumping to 12 cases on Nov. 28 and 19 new cases per day on each of the following four days, according to the Yale COVID-19 data dashboard. Eight new cases were reported on Dec. 3.

Although Forman said that the results of testing on Dec. 3 “looked pretty good,” he explained that they were affected by the requirement that undergraduate students living on campus take two COVID-19 tests this week. Increasing the amount of total tests administered resulted in lower positivity rates, Forman explained, and students who are more COVID-cautious were more likely to abide by the updated testing recommendations.

“What we’re seeing is that the figures are not unexpected for what we expect at this time of the year in Connecticut based on what we learned from last year,” Forman said. “Yale still has mitigation measures already in place. We only have a couple more weeks to go. I think what’s going to be more important is, what will things look like in the middle of January when students come back? At that point, is the Omicron variant going to be an additional challenge, or is it possible that at that point we realize it’s a less severe disease, or more severe?”

In early November, Boyd announced that Old Campus’s McClellan Hall would no longer be used as isolation housing, returning to its original function as mixed-college housing for upper-level students. On-campus isolation housing capacity currently stands at 71 percent, the lowest it has dipped this semester. Were that number to creep into “30s or 40s,” Forman said, administrators would likely pursue more dramatic policy changes.

“The good news is that the University has sufficient isolation space,” said Forman. “The numbers don’t look like they will get so out of control that we’ll have to shut down anything between now and final exams, but it does create lots of roadblocks for us in the next couple of weeks.”

While the current campus positivity rate is 0.70 percent, that number breaks down differently across various demographics. The undergraduate positivity rate is 0.57 percent and the positivity rate among graduate and professional students is 0.62 percent. Among faculty and staff, the positivity rate is 1.15 percent.

Forman predicted that the spike in cases would lead to “an unusual end of the semester,” noting that he has already had students in his undergraduate classes test positive for COVID-19 in recent days. He added that professors will likely have to administer online exams to students in quarantine and that some students might need to defer taking exams altogether due to illness.

Yale could meaningfully reduce COVID-19 cases on campus without making drastic changes to student life, Forman said, adding that tightening restrictions on in-person gatherings may have a significant impact on positivity rates.

“The more we curtail activities, the closer we’ll get to a normal end of the semester,” Forman said.

Boyd told the News that events that comply with University COVID-19 guidelines, or unique COVID-19 safety plans approved by the University, would likely be able to continue in person for the rest of the semester.

The safety of informal gatherings, Boyd said, could be harder to assess.

“Pay attention to the level of crowding, the duration of the event, and the ventilation in the space — and don’t forget to wear your mask,” Boyd advised.

Martinello also recommended that students continue to follow public health guidelines, emphasizing in particular that they avoid dining indoors at restaurants — a precaution University administrators stressed last year.

This fall, communities across the United States with lower vaccination rates have borne the brunt of the Delta variant’s impact — by contrast, the current increase in campus cases appears unlinked to Yale’s vaccination rates. According to Yale’s COVID-19 data dashboard, campus vaccination rates — updated weekly and current as of Nov. 29 — are considerably higher than state and national averages. 99.7 percent of undergraduate and 98.9 percent of graduate and professional students are vaccinated, while 97.1 percent of faculty and 93.2 percent of staff have reported receiving the jab.

Still, Forman noted that those who received their vaccine more than six months ago and have yet to receive a booster shot may experience “waning immunity,” making them more likely to contract and spread the virus.

The University does not currently publish data on what portion of the Yale community has received a booster shot.

A significant portion of the student body receiving their booster shots over winter break, Forman said, could have a meaningful effect on campus life when students return in January.

“We’ll know more once we know more about the Omicron variant,” Forman said. “If we were only talking about the Delta variant, I think [everyone receiving their boosters] would help us enormously. We’d be able to have a very normal spring semester, better perhaps than even the fall.”

Martinello also said that while booster shots are not currently mandated by the University, students should still get them as soon as possible.

Several students told the News that they worried COVID-19 cases on campus were not being treated as seriously as they should be by University administration.

“I don’t really think that Yale’s doing that great of a job right now,” Alex Abarca ’24 said. “The rationale is probably that our people are vaccinated, and really the only people going to hospitals at this point are the unvaccinated. But I still think it’s really bad how it’s not being taken seriously anymore.”

Leo Mateus ’24 was unaware of the amount of students who had tested positive for COVID-19, which he described as a “pretty surprising number.”

Brook Smith ’25 added that she worried the University’s communication to students had not been enough to effectively convey the gravity of the situation.

“I do worry that Yale’s messaging may not be enough to get the point across to students that now is the time to buckle down on safety,” Smith said.

Claire Barragan-Bates ’25 concurred that the University should be doing more to communicate with students about the status of COVID-19 on campus, as well as to promote students getting booster shots to their vaccines.

Although Barragan-Bates got her booster shot two months ago, she said that she did not know many students who had also gotten theirs.

“I think that the university should put in the same level of effort with encouraging Yalies to get the booster shot as they did the initial vaccine, but I am not seeing the same level of access provided for these booster shots to the student population as I saw with the flu shot and the initial vaccination series,” Barragan-Bates wrote in an email to the News.

But Barragan-Bates added that she thought the University had otherwise done “a decent job” keeping positivity rates low relative to peer institutions.

Spangler emphasized to the News the importance of “engaging all of our levels of protection,” including testing, masking and vaccinations.

“We are very carefully and continually reviewing COVID-19 cases on campus and in the surrounding area and state,” Spangler said. “The recent increase in cases on campus does mirror increases in the broader region and, in many instances, cases appear to have some association with recent travel and informal social gatherings.”

Yale requires all students, faculty and staff to be vaccinated against COVID-19 unless they have a medical or religious exemption approved by the University.