Tori Lu

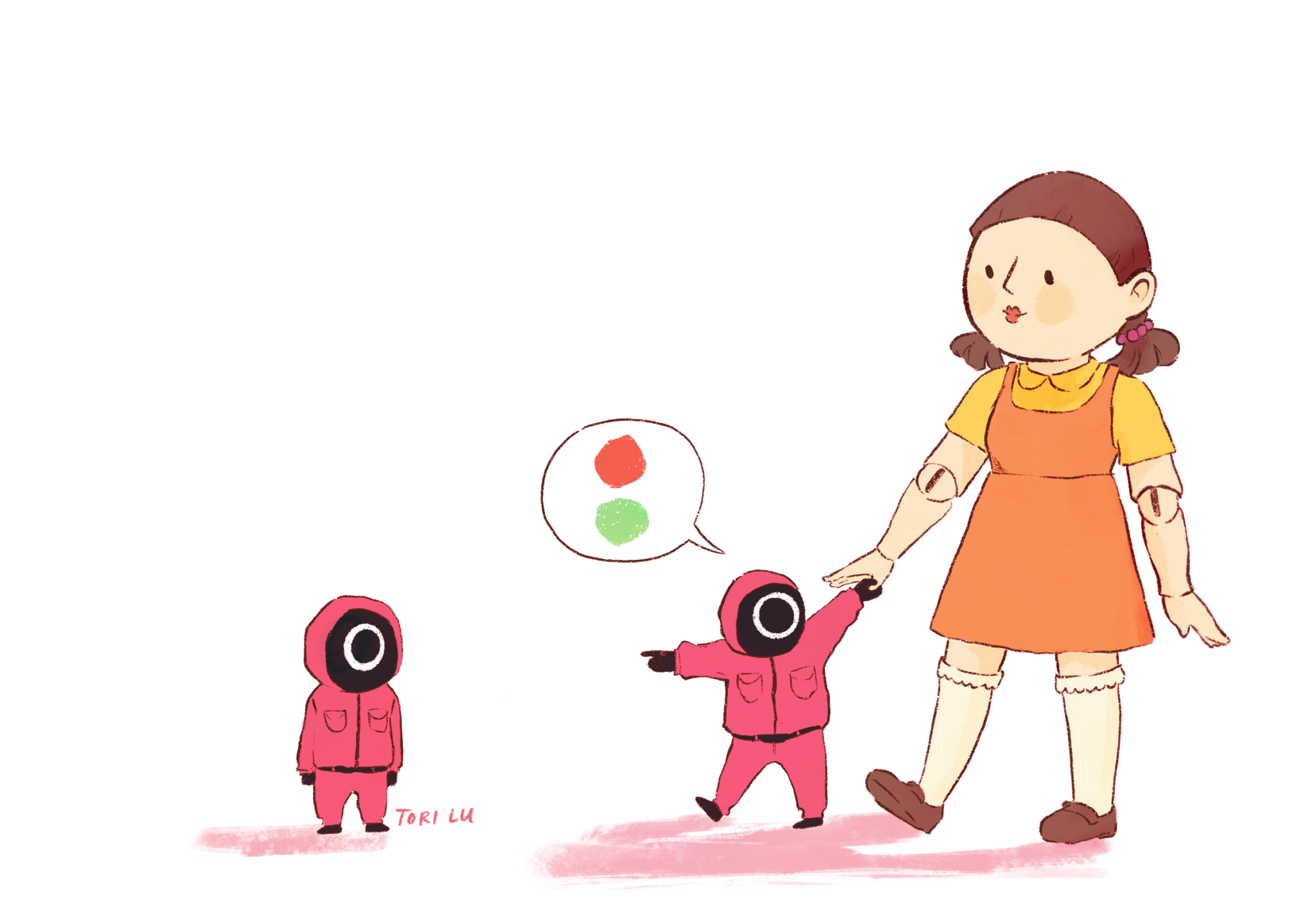

“Squid Game,” a South Korean dystopian drama, is Netflix’s “biggest ever” series, with an audience of over 110 million viewers worldwide. The premise is simple. Supposedly random people are approached by a representative — played by the charismatic Gong-Yoo, if you’ve ever watched “Goblin” or “Train to Busan” — and offered a chance to play the Squid Game for an insane amount of money. As it turns out, these participants were specifically chosen for one reason: their immense debt. Once they’ve agreed to the game, they are transported to an isolated resort to compete in children’s games such as Red Light, Green Light and stepping stones. What is not revealed to the players, however, is that the consequence of losing is death.

The outcasts of society are scammed into the game — tossing marbles across the floor or licking burnt candy, in order to not be licked by a bullet. Sweat drips down their shoulders as they play tug-of-war, trying not to stare at the blood streaks left by their friends who fell to their deaths moments before. The audience is hypnotized by the suspense, distracted from the absurdity that human lives are being determined the same way kindergarteners win candies and bragging rights.

But how far is the show from the truth, really? The supposedly dystopian premise of Squid Game is eerily relevant to South Korean society today.

In every game, the players are regularly forced to choose between betraying their friends or facing death. In trying to survive, players form close-knit bonds, ignoring the foreboding knowledge that there can only be one winner in the final game.

Cho Sang-Woo, an elite graduate of Seoul University — the Yale of Korea — joins the game in order to win money and conceal his failed business from his mother. Abdul Ali, an immigrant worker scammed by his factory, joins in hopes to provide for his family. Sang-Woo and Ali form an extremely close bond, especially because Ali finds comfort in the intelligence and kindness Sang-Woo ostensibly portrays. However, they quickly learn that the only way to survive is to cheat their way through. It’s a brutal mentality: kill or be killed. Abdul and Sang-woo start to play a simple game where they guess if the other player has an even or odd number of marbles. Sang-woo continues to lose, and decides to trick Abdul into believing that there is a game where they can both win. Abdul chooses to be loyal to Cho Sang-woo and watches as Sang-woo creates a bag for Abdul to hold his marbles. It turns out Sang-woo has unknowingly swapped Abdul’s marbles for pebbles, and we heartbreakingly watch Abdul die as a result of Sang-woo’s ruthless deception.

This merciless mentality is cultivated among the lower class in South Korea. South Korea is notorious for their brutal education system. Students are given one chance to take an annual test called the “Civil Service Exam,” which determines whether citizens can become white-collar workers and achieve socio-economic stability. The test is inherently biased because rich families can invest thousands of dollars into prep academies to prepare their children, while children from poor families often have to work instead of study. The lower class is then forced into the same mentality as the players in Squid Game: kill or be killed. Students enter a system where their closest friends become their fiercest enemies, resulting in a cut-throat environment where students are left scrambling for a sliver of openings.

There is another option: suicide. Two young girls of similar age, Ji-yeong and Sae-byeok, form an unusual friendship. As they learn more about each other’s pasts, both transform from hard-shelled independents to companions with a soft spot for one another. In the same marble game, Ji-yeong and Sae-byeok talk about their supposed future together, where they will share a drink in the Maldives. It is a moment of humanity in this inhumane game, which inches towards a knowingly devastating end because Ji-yeong drops her marble and chooses to lose the game. Her last words are, “I’m honored that we were partners,” before a bullet is put into her head. Squid game’s sadistic message is clear: morals be damned, you’re still going to be dead.

These tensions all make great cinema, but as a South Korean, I feel uncomfortable seeing the jarring similarities to South Korea today. For example, Squid Game reveals how morals can bend towards the social elite. A recent incident regarding the cause of two students’ deaths highlighted the economic injustices that are apparent in South Korea. Son Jeong Min, the son of a fairly affluent family, was found dead in the Han River. His death raised headlines on all the major news reporters, and the nation rallied around the determination that they would solve his case. Meanwhile, Lee Seon Ho was killed in a tragic accident while working at a container cargo company. He worked at minimum wage at this factory in order to pay for his college expenses. Seon Ho was crushed by the door of another container, and instead of helping him, his supervisors apathetically reported the accident. Due to the company’s inaction, Seon Ho was treated too late and painfully succumbed to his injuries.

The drastic difference in treatment of these two scenarios is not new to South Korea. Millions of people work in unsanitary conditions at minimum wage, risking their lives for little money. Only 12.5% of salary workers are in a trade union, meaning that workers are often left powerless. South Korea has a huge issue with fraud, as the lower class will borrow money from “loan sharks” to pay for their rent or other expenses, which often leads to violence or murder when the money is not paid back.

Squid Game — the game — embeds within itself a rigid hierarchy that is inherent to its functionality. At the bottom are the players, arbitrarily numbered between 1 and 456. Although we get to know some of their names, it becomes clear that the names aren’t necessary to the guards. After all, almost half of the players die by the first game of Red Light, Green Light. Amongst the guards, there is also a hierarchy. It goes in the following order, from top to bottom: squares, triangles and circles. Those in the lower hierarchy are not allowed to talk unless spoken to by a superior. Above them is the Front Man, who oversees the operations of the games and makes decisions governing the players’ lives. However, the entire premise of the games is to please the VIPs, an anonymous group of people who are blatantly presented as mostly American — southern accent and all.

Squid Game shows the effects of hypercapitalism in South Korea, and the foreign attitudes of the VIPs add another dimension to this dystopia: Westernization. The Western ideals of capitalism and economic success, despite their political fragility, were the blueprint for South Korea’s shift towards capitalism.

Aside from South Korea, the biggest audience that watches Squid Game is in the US. According to Morning Consult, one in four Americans say that they’ve watched Squid Game. Squid Game embeds the effects of orientalism in its storyline, showing how the American VIPs find pleasure in watching the outcasts of South Korea fight to their death. The Americans make overarching generalizations about the characters and, in essence, South Korea, which is extremely similar to the way Western audiences perceive South Korea today.

The Western world both contributes to and enjoys the benefits of South Korea’s hypercapitalism—BTS performing at the Grammys, Korean food being popular across nations, and even movies like “Squid Game” and “Parasite” bringing in huge revenue from an international audience. Ironically enough, both “Squid Game” and “Parasite,” which are conceptually anti-capitalistic, profited immensely off of capitalism in America. This foreign attention feels uncomfortable because these films are extensions of real life in South Korea.

The VIPs of Squid Game are relevant beyond just modern contexts. After Japanese imperialistic rule ended in 1945, South Korea began to rapidly modernize, using corporations and technology to catch up with the Western World that was becoming increasingly dependent on capitalism. In fact, the United States helped carry out the first wave of land reform that changed South Korea from largely agricultural to urban. This is the same United States that today looks on and reaps the entertaining benefits of South Korea’s crumbling socio-economic structure. South Korea today no longer feels like one nation, fragmented by class and people who have justified their vices with individual success. Families of generational wealth, called chaebols, hold most of the wealth in South Korea. Cities like Seoul and Hongdae are bustling metropolitans that generate hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue, while rural cities like Gwangju and Daegu are deteriorating or in the process of being gentrified. Doesn’t this sound familiar?

The Western World reaps the benefits of Korea’s hypercapitalism, including enjoying the action-filled Squid Game, while simultaneously being one of the main influences on hypercapitalism in the world today. Meanwhile, for many South Koreans, this TV show leaves a bittersweet taste in their mouths. On the one hand, they — or at least I — are glad that Korean culture is being recognized on a global scale, but soon the fear sinks in that “Squid Game” is only a slight exaggeration of reality.