FEATURE: Undefining Misbehavior

How teachers have been reimagining discipline in New Haven Public Schools

Yale Daily News

How did my words or actions make you feel? What do you wish I understood? What do you wish had happened instead? What do you need from us?

Teachers and students sit in circles, share stories and ask each other these questions. This process, which centers affective language, lies at the heart of restorative practices.

Restorative practices — with roots in ancient Indigenous communities and several of the world’s most practiced religions — focus on both prevention of and response to student behavior that is disruptive or harmful to themselves or others. These relationship-focused practices aim to lessen schools’ reliance on punitive discipline that some say criminalize misbehavior without reducing it and perpetuate racial inequity in schools. And amid the COVID-19 pandemic, teachers in New Haven Public Schools, a district with 44 schools and 20 magnet schools that serves over 20,000 students, have turned to restorative practices to address student behavior and student needs that the pandemic has helped them better understand.

“I’ve had situations where kids have done something fairly serious, and in conferences, the teacher completely retracts their original request for punishment because of the context of the kid’s situation,” said NHPS Director of Restorative Practices Cameo Thorne.

Thorne emphasized that context can completely change how a teacher responds to disruptive behavior — when they try to understand what’s really going on, restorative practice becomes an exercise in cultural competency for both teacher and student.

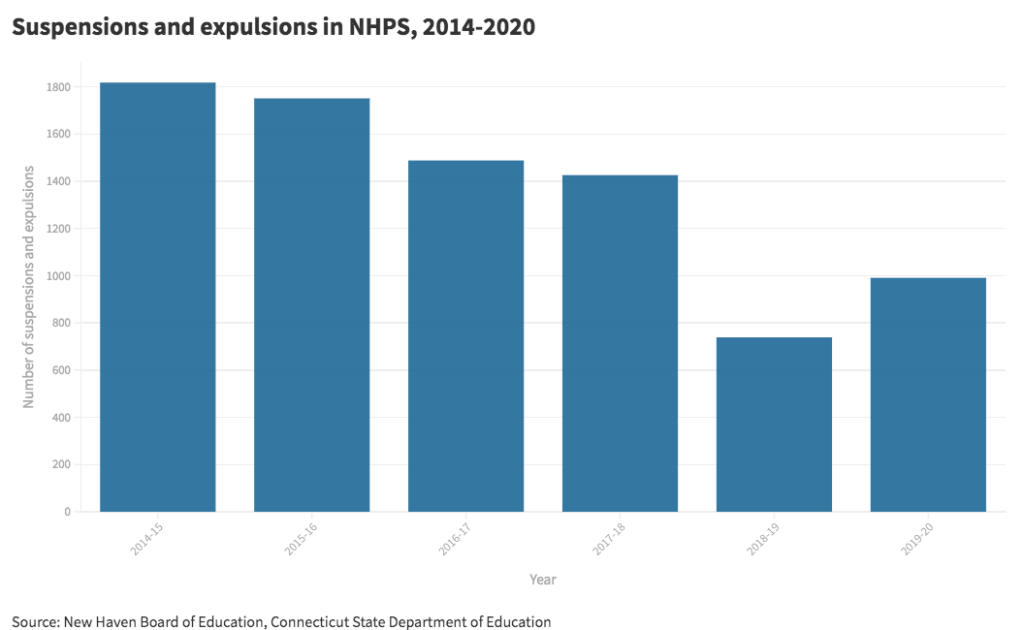

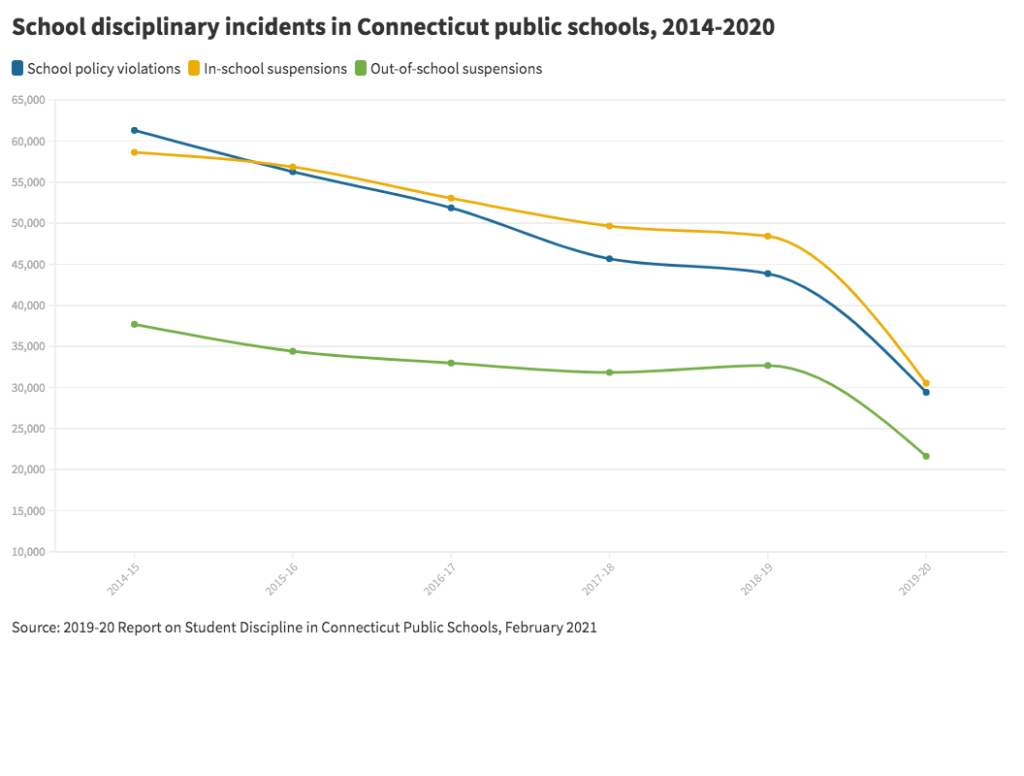

In recent years, alongside the growth in restorative practices, fewer students are being disciplined in traditional, punitive ways. According to the Connecticut Board of Education’s 2019-20 report published in February, the total number of suspensions, expulsions and school policy violations in Connecticut all decreased by more than 12 percent over the last six years. In NHPS, 1,818 students were suspended or expelled in the 2014-15 school year, while in the 2019-20 school year, 991 students were suspended or expelled — a nearly 50 percent decrease.

Racial disparities in exclusionary discipline remain, nationally and in New Haven: Since the 2014-15 school year, suspension rates in NHPS have ranged from 60-64 percent for Black students and hovered around 30 percent for Latino students — but fall at just 5-7 percent for white students, according to a 2019 Board of Education presentation on suspensions. And although data on student discipline from this past school year is not yet available, statistics on learning loss from the national testing organization NWEA have made clear that COVID-19 has hurt Black, Latino and low-income students hardest.

NHPS teachers like Thorne said the pandemic has helped them better understand what their students are struggling with, facilitating a shift toward a classroom dynamic centered around restorative practices and social-emotional learning — the latter focuses on self-awareness, social awareness and relationship building in education. But they said the pandemic’s long-term effects in bolstering restorative practices could be precarious without wider systemic change to build community and mitigate the disproportionate impact of punitive school discipline on Black and Latino students.

“I’d like to think that collectively, teachers will be more aware [of restorative practices] because we’ve seen so many students struggling,” said Chris Kafoglis, a high school math teacher at Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School, an interdistrict magnet school in NHPS.

Phoebe Liu

NEW HAVEN’S RESTORATIVE PRACTICES AND ‘MISBEHAVIOR’

At the root of student discipline in the Elm City are several codes of conduct, one for the entire NHPS system and one for each individual member school. These codes set the tone of student disciplinary procedures across the district, delineating how schools respond to student violations and what counts as “misbehavior,” if the term should even be used at all.

NHPS’ broader shifts toward restorative practices have been reflected in changes to its code of conduct. In January 2021, the Board of Education unanimously passed a revision of the code: the NHPS’ draft Public Schools Code of Conduct. The policy is part of an effort that began in 2014 with a $300,000 award from the American Federation of Teachers Innovation Fund grant to the New Haven Federation of Teachers, the local teachers’ union, to train teachers in restorative practices and run pilot restorative practices at the school level. Over the next seven years, a group of parents, administrators, teachers union members, mental health professionals and legal experts collaboratively rewrote the code.

The code is centered around the principles of restorative practices, which include social and emotional learning, collaborative approaches to solving community issues and repairing harm. It defines restorative alternatives to punitive discipline. For example, if a student commits an infraction of a school code, a teacher should check in on them individually first — part of a framework called positive behavior interventions and supports, or PBIS — instead of defaulting to detention or suspension. The new code includes the phrase “restorative” 71 times; the 2019-20 code of conduct mentions it once.

Notably, unlike in most student conduct handbooks, one word is absent from the more than 50-page document: misbehavior. Instead, the district uses the phrase “behavior that is disruptive or harmful to learning.”

“[The term ‘misbehavior’] is not a neutral word; it starts with the idea that I know for a fact that you’ve done something wrong,” said Thorne, who helped draft the code. She successfully advocated for removal of the word “misbehavior” from the policy. “Then, from that perspective, I’m already in the place where I am not open to hearing what it is you might say that might change everything.”

Teachers emphasized that using the term “misbehavior” can overlook the underlying social-emotional and physical needs that almost always lie at the root of disruptive behavior. And more often than not, these characterizations contribute to the disproportionately high number of Black and Latino students who are subject to punitive discipline.

“If you start with ‘I haven’t already decided who’s bad or who’s good,’ that sort of balances the knee-jerk reaction of a cultural difference that is rooted in racism and bias,” Thorne said.

David Low, a high school math teacher at the Sound School, an aquaculture-based school in NHPS, agreed with Thorne that the term “misbehavior” can be counterproductive.

“What we would traditionally, on a societal level, call ‘misbehavior’ is a symptom that something else is wrong,” Low said.

When students “misbehave,” Low responds by engaging with students and connecting to their identity rather than seeing them as “doing something wrong.” He starts by addressing the student by their name and goes deeper from there, making analogies based on students’ interests and going the extra mile when he can. In his four-student ocean engineering class, he bought each student a 3D printer and delivered it to their home.

While some other teachers — such as Kelly Hope, a high school English teacher at New Haven Academy, an interdistrict magnet school in NHPS — did use the term “misbehavior” to describe disrespectful or disruptive behavior that prevents others from learning, all teachers interviewed expressed a desire to approach their students in a way that mirrored language in the NHPS code. They wanted to address their students respectfully and relationally, even when students behaved in a way that was not in accordance with class expectations.

MORE INTENTIONAL WAYS TO ADDRESS DISENGAGED STUDENTS

Although they had different approaches, Low and three other teachers spoke about one student behavioral issue they encountered every day, an area greatly exacerbated by the pandemic: low student engagement, due in large part to remote learning. They said that low student engagement was frustrating and complicated the process for teachers to understand how students are doing or how they are absorbing the material. And ultimately, low engagement compelled some teachers to look for root causes of disengagement — which led them to shift toward a restorative mindset.

“[Students having their videos off] meant that we were less engaged and less connected and that they were less connected to us,” Low said. “It didn’t feel personal — they could basically sit there doing nothing, and you’d never know it unless they actually spoke. It was an absolute horror show.”

Even though Low spent time and money driving to his students’ houses and dropping off materials for engineering and robotics classes, he often had no idea whether students were even using the equipment. Because students’ cameras were off, he had trouble fostering a highly engaged virtual classroom.

Kafoglis agreed: “My number one complaint the teachers have is kids not engaging, not being there or not attending. Most of the behavioral issues we’ve faced have had to do with the social-emotional wellness of students.”

Throughout the period of virtual learning, Kafoglis cold-called students often to increase engagement — but in a way that emphasizes that a teacher cares, not in a way that makes them feel like they’re in trouble for doing something wrong. He emphasized that when students are not engaged, he doesn’t want it to be a “relationship-killing situation.”

“If a student doesn’t respond, I would recommend against saying to the student, ‘where are you?’” Kafoglis said. “That sort of tone won’t get you anywhere” and does not help the “particular relationship between you and the student … [it] damages what you’re trying to create as an overall classroom environment.”

Other teachers took more active steps during class sessions when students were disengaged while remaining aware of students’ individual situations. Ramya Subramanian, who teaches at Elm City Montessori School, NHPS’ charter school, recognized that students were fatigued from virtual learning, but she made sure they had their videos on and were unmuted when they spoke. When students didn’t engage, she said to the class, “I need you to make one comment or ask one question.”

Still, Subramanian said that for as long as she remembers, her teaching at ECMS has been centered around social-emotional learning and restorative practices. She emphasized that “you can tell when there are other things going on,” and in those cases, she will reach out to a student individually after class.

But as students have started to learn in classrooms again, most educators said engagement issues have lessened as students get to see each other face-to-face again. Now, Kafoglis and three other teachers added, teachers are more sensitive to other cues about students’ social-emotional wellness; they’re more inclined to look for underlying causes in disruptive behavior rather than apprehending and punishing.

“Now, you know, if a kid is misbehaving, instead of thinking, ‘how am I going to correct this?’, the thought is, ‘what’s happening, what’s wrong?’” said Maria Parente, Yale’s coordinator of community programs in science, who works with NHPS students as part of her programming. “Let me talk to this kid … and find out what’s going on.”

BETTER SUPPORT SYSTEMS

To meet student behavioral and social-emotional needs, and ultimately, address root causes of student “misbehavior,” multiple schools have bolstered their academic support programs, advisory sessions and social-emotional learning circles — a key component of restorative practices.

The Sound School, where Low teaches, increased the frequency of its advisory period from one day a week to five days a week amid the pandemic. Advisory periods are small group sessions not tied to explicit academic work but instead focused on restorative or connective conversations, virtual circles and social-emotional learning. Over the last year, schools have had these sessions both virtually and, when permitted, in person.

“We knew the challenges of their emotional needs are going to be amplified this year,” Low, who leads one such advisory group, said. “I think people got even more invested in it during this remote time.”

Low doubts the daily advisory sessions will continue post-pandemic, but guessed that the school might bring their frequency down to three days a week, still an increase from the pre-pandemic sessions.

Other schools have similar practices. ECMS holds daily 25-minute social-emotional learning circles, which Subramanian said help students practice strategies for dealing with interpersonal conflict or other stressful situations, even though they take up teaching time.

Susan Ellwanger, who teaches high school English at New Haven Academy, said her school created daily advisory sessions with a restorative lens at the beginning and end of each day for “bonding that helped the students engage.”

These systems of support are restorative practices that serve to proactively prevent misbehavior, according to Thorne, who said one of the “big misunderstandings” surrounding restorative practices is a sense that it’s “all about repairing harm.”

“Putting people in settings … to listen to each other and hear each other is the first part of the work, and really it should come before the healing of the harm, to build culturally competent communities,” Thorne said.

INCREASED BEHAVIORAL LENIENCY?

Taken together, the shifts toward restorative practices have contributed to increased discourse on behavioral leniency, or how strict teachers want to be with their students, especially those who may be struggling.

Some teachers, such as Hope and Subramanian, said they largely kept their expectations for behavior and school work the same — while understanding that there are challenges each individual student faces.

Subramaniam, who said she would like to imagine herself as “always warm and demanding,” added that part of keeping her expectations similar was possible because ECMS, as a charter school, did not have to align with NHPS’ phased reopening plan and has conducted in-person instruction since last fall, months before NHPS entered a hybrid learning model.

For Low and Ellwanger, however, expectations for virtual learning amid a pandemic were inevitably different, they said.

“Everybody was forced to be more lenient; we gotta have empathy for their kids and give them a lot more leeway,” Low said. For years, he has accepted work “at any time from any kid” as long as they had completed it but said that due to the pandemic, more of his colleagues have adopted a similar mindset.

Ellwanger also said she has always offered leniency around work and deadlines when students need it, but during the pandemic, more students have realized that it is actually okay to take her up on her offer of flexible deadlines.

Even for more severe disciplinary issues, which teachers largely said were few and far between, the pandemic caused teachers to develop an increased focus on compassionate approaches to disruptive behavior.

Hope, for example, said that early in the remote learning period, there were two instances where she removed a student from a virtual classroom due to disruptions that were harming others’ learning — in both instances, a student repeatedly turned their microphones on with music blaring that made it difficult for Hope to continue class. Even though she undertook a “punitive” action, she supported students in social-emotional learning by following up individually after the incidents to connect with them.

“[Removing a student and filing a behavioral log] is a way for the students to take responsibility for their learning, education and behavior, but also for me as a teacher to say ‘I am not going to negatively penalize you and never allow you to recover,” Hope said.

Subramanian, who teaches at ECMS, took the focus on social-emotional learning even further — she disagreed with the premise of asking someone to leave a learning space or shutting down any kind of communication but rather spoke about addressing incidents like Hope’s through positive reinforcement in the form of social-emotional learning circles — something that can be implemented as students have returned to in-person learning.

“Rather than saying, ‘you need to leave the [discussion] circle,’ if you use positive discipline, back again to those social-emotional learning circles, where you have agreed on the norms, what does it look like?” Subramanian said. She said that in the circles, she asks questions, observes and gives mini lessons. “You fix [the issues] and there’s no need for you to be crying out, that’s wrong or that’s not right … so that [kids] feel like they’re being targeted by the adults.”

A DEEPER DISCONNECT

Regardless of whether a behavioral issue meant lack of student engagement or something much more severe, all teachers interviewed spoke about the need to address the underlying causes of student “misbehavior” especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, and most used the language of restorative practices to do so.

Low said that behavioral issues such as low engagement levels are emblematic of a deeper disconnect between intrinsic and extrinsic motivations. Learning how to distinguish between them and focus on the intrinsic motivators — deeper investment in academic material and a sense of community — can help prevent disruptive behavior in a restorative way, according to Low and Thorne.

“There’s a pile of motivation in every person,” Low said. “And the problem is that extrinsic and intrinsic motivation are inversely proportional. The more externality you give to the learning — grades, rewards, punishments — all of that leads to low-level engagement.”

Low aims to build intrinsic motivation in his students from the very beginning, by deep relationship-building and by avoiding an urge to control every aspect of a student’s behavior.

“Put simply, how many times have you heard people talk about students owning their learning? How do you actually do that?” Low asked. “You can’t have externally and internally motivated work simultaneously. It’s either a lot of one or a lot of another. So the more control you attempt to exert, the more you’re going to disengage the intrinsic motivation of any person to learn anything.”

Subramanian said that, possibly in part due to Zoom fatigue from the period of virtual learning, “the work itself does not excite them, and that continues to this day,” which she said is an ongoing struggle. Ellwanger expressed a similar sentiment and pointed to advisory time as a way for more intrinsically motivated students to mentor others.

Generally, teachers emphasized the role of social-emotional awareness and relationship building with students in building intrinsic motivation.

“We are training for empathy, recognition that another person’s perspectives and experiences are real and we need to be as aware of them as possible,” Ellwanger said, describing the premise of restorative justice circles — putting one’s own perspective aside and trying to understand another person’s background or their point of view in a specific situation.

THE NEED FOR SYSTEMIC CHANGE

Although restorative practices and a focus on social-emotional learning are taking hold in NHPS, educators said more cultural and systemic change needs to happen.

Claudia Merson, director of public school partnerships between Yale and NHPS, commented on the broader cultural shift. Merson cited data showing that the district has invested in restorative practices since before the pandemic — referencing the sharp decline in suspensions and expulsions in the 2019-20 school year in NHPS.

Phoebe Liu

“[Moving to restorative practices] is a culture shift that will take some time, but I think that it starts with the commitment to do it, and then you figure out how to make it happen,” said Sarah Miller, a community health organizer for youth mental health organization Clifford Beers, New Haven Public School Advocates member and parent of two elementary school students at Family Academy of Multilingual Exploration. “It requires a vulnerability that’s very hard for adults.”

Miller added that creating restorative practices circles in response to conflicts is not enough to effectively prevent behavioral issues and create a positive learning environment. But even though there’s still much to be done, the district has come a long way, according to Low, who has taught in NHPS for almost 40 years, and Hope, who grew up in Newhallville as a student in NHPS.

“When I started, it was ‘don’t smile till Christmas,’ and I went with that for many, many years,” Low said, referencing a zero-tolerance approach to classroom discipline. “The way we handle things now is much more effective now in terms of developing human beings, which is, if a student is having difficulties, it’s much more effective to develop a relationship with the kid.”

Hope said that when she was a student in NHPS, “if you were disruptive, you were going straight to in-school suspension … or [even] … being suspended right out. Now, there’s room for having those conversations, correcting the behavior and then coming back into the classroom.”

Thorne said that over the years, many teachers have embraced the concepts of restorative practices in schools. But she emphasized that “when it comes to implementation, we need to coach each other.”

In her capacity as director of NHPS’ restorative practices project, Thorne is currently licensed to train teachers in restorative practices. She planned two-day training sessions with educators over the summer and extending through the fall, during which educators explore their own values and talk through scenarios to understand how to apply restorative practices in classrooms.

Hopefully, Thorne said, the city’s Youth and Family Services department will devote resources toward additional trainers and training for restorative practices. The department has allocated some money for this purpose, she said in June, although the funds will not be used to hire additional employees but instead to retool current positions. For example, she plans to facilitate moving people who oversaw in-school suspensions into a broader “school support” position.

Genuine understanding and implementation of restorative practices go far beyond individual relationships with students and builds on a sense of community trust, according to Thorne and Mira Debs, executive director of Yale’s Education Studies Program and a founding board member of ECMS.

“One of the pieces about restorative justice is that it really takes time to implement,” Debs said. She commented on how, as students are returning to the classroom, the comfort of parents, students and teachers in trusting that “school is a place that’s safe and will do things to keep them safe” is critical to the success of restorative practices.

Low agreed: “Misbehavior is systematic. It’s just that misbehavior has had so much less to do with the individuals than with the construct in which they’re being placed.”

Hope, Miller and Thorne emphasized the school-to-prison pipeline and its relevance in NHPS, a district where two-thirds of students are on free and reduced price lunch, 36 percent of students are Black or African American and 47 percent of students are Hispanic or Latino.

“Kids of color, especially boys of color, are subject to much more punitive kinds of discipline, and if you create alternative structures for dealing with issues, then that minimizes that sort of targeting,” Miller said.

Thorne spoke about restorative practices’ potential positive effects in closing this disparity: “Restorative practices honor everybody by making sure everyone has a voice, and the people ‘doing’ the discipline aren’t even the ones making the decisions.”

Still, looking ahead, Miller said that even successful implementation of restorative practices may not be enough. This will be especially true in the current school year, as students return to a more normal form of learning despite continued worries about COVID-19: In NHPS, students are proceeding with in-person instruction with a teacher vaccine mandate, student mask requirement and weekly testing. School psychologists nationally anticipate greater concern over student engagement and social and emotional well-being, while New Haveners, in a mid-August rally, expressed both excitement and apprehension for the upcoming year. Amid continued uncertainty, teachers stressed the importance of focusing on a single bottom line: student support, at both individual and systemic levels.

“Some of the [restorative] practices can help unearth what’s really going on, but there have to be systems of support to really address what’s going on,” Miller said. “The practices themselves won’t solve that.”