“The Green Knight,” directed by David Lowery, is unafraid to subvert cinematic expectations. As a modern adaptation of an old poem, the movie plays with the structure of its source material and various styles of visual representation. For those not familiar with the original poem, Sir Gawain goes on a quest to prove his honor and chivalric worthiness to inherit King Arthur’s crown by playing a deadly Christmas game with a mysterious “Green Knight.” Through his trials, we find that Sir Gawain has a streak of cowardice alongside his chivalric nature, but in the end, the game is revealed to be just a game, and the Green Knight reveals himself to be the helpful Lord Bertilak. It’s an unexpectedly unconventional story, where the hero is not always heroic — in his final confrontation with the Green Knight, Sir Gawain keeps on a magic green sash which shields him from all harm — and the stakes are ultimately toothless.

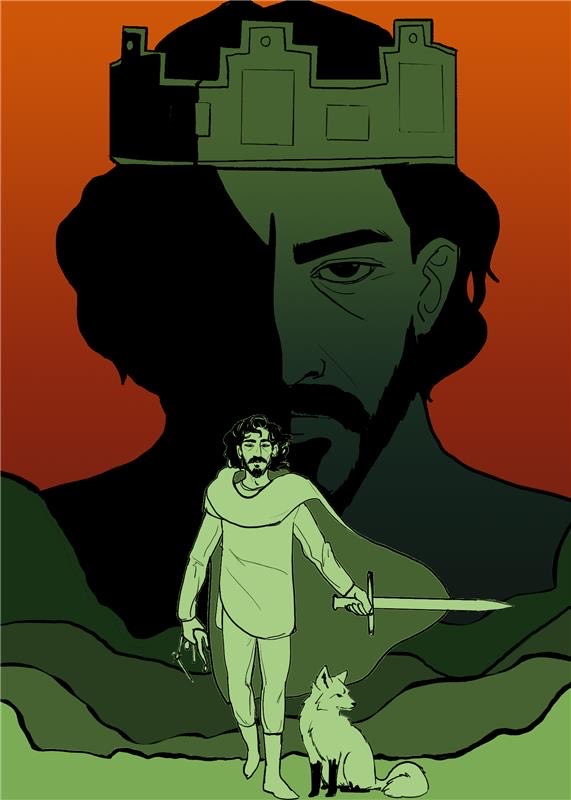

Arguably, the movie has a more conventional ending given chivalric tropes and morality tales about bravery and virtue, where Sir Gawain honorably takes off his invulnerability-granting sash and the Green Knight is separate from Lord Bertilak. However, it still stands out as an uncommonly quiet, meditative film for a story about medieval knights. Sir Gawain, portrayed by Dev Patel as a struggling knight, is lost, confused, sad and wet for the majority of the film, but is always hot. That’s not just my opinion; four separate characters in the film show romantic and/or sexual interest in Sir Gawain, and the camera itself lingers longingly over his figure for the entire movie. His form itself is reproduced into art, first as a puppet and then as a haunting upside-down painting — which he poses for in the second-most sexually suggestive painting scene I’ve seen in cinema. This adds a fascinating new layer to his self-doubt: He’s competing not only with the other knights of the Round Table, but also with the representations other people have of him, and on a meta-level, the original Sir Gawain from the poem.

Given the central focus on Sir Gawain, and the fractal-like quality of his multiple representations — including visions and hallucinations — in the film, why isn’t the movie called Sir Gawain instead of The Green Knight? There’s a joke about how English classes teach students to overanalyze meaningless segments of literature, down to “Why are the curtains blue?” Regardless of whether that critique is applicable to the discipline of literary analysis as a whole, it turns out that the color green itself is a major motif for the film, to the point where a character delivers an entire monologue about green. Near the start of the film, after Sir Gawain cuts off the Green Knight’s head, there’s a haunting shot of red blood flooding over a moss-ridden floor, towards an equally plant-eaten axe. It’s a long, long moment — because it’s meaningful. That one image encapsulates the upcoming monologue about how red — lust and life — is inevitably replaced by green — rot, decay, new kinds of life — and could be the thesis statement of the movie as a whole. And although Sir Gawain rides out with a striking turmeric-yellow shawl at the film’s start, in the end, his most defining article of clothing becomes a green sash, making him, too, a kind of “Green Knight.”

This movie is likely not for everyone; it eschews action scenes for long, lingering silent shots of the wilderness. If I didn’t like this film, I would say that it was a feature-length slideshow of beautiful desktop wallpapers or T-shirt designs. But I do like this film, and so I’ll say that the pauses between action remind me of Shadow of the Colossus’s emphasis on decay — now we’re back to green — nature’s re-taking of a crumbling civilization. No matter how much the characters push towards chivalric ideals — how valiantly Sir Gawain strives for the crown — the moss is always creeping around the corner. And the wilderness is never fully kept at bay.

Claire Fang | claire.fang@yale.edu