Dora Guo

The sea had already killed two people that summer. A woman who had traveled south from Médou eagerly waded into the water with her skirt hoisted up so that the hem only brushed the waves. A wicked riptide encircled her bare knees and dragged her out deep into the water where she fought so hard to breathe that she drowned. A week later, it ensnared a second man, a French tourist. He did not drown, but the Lakulese who dove in after him did.

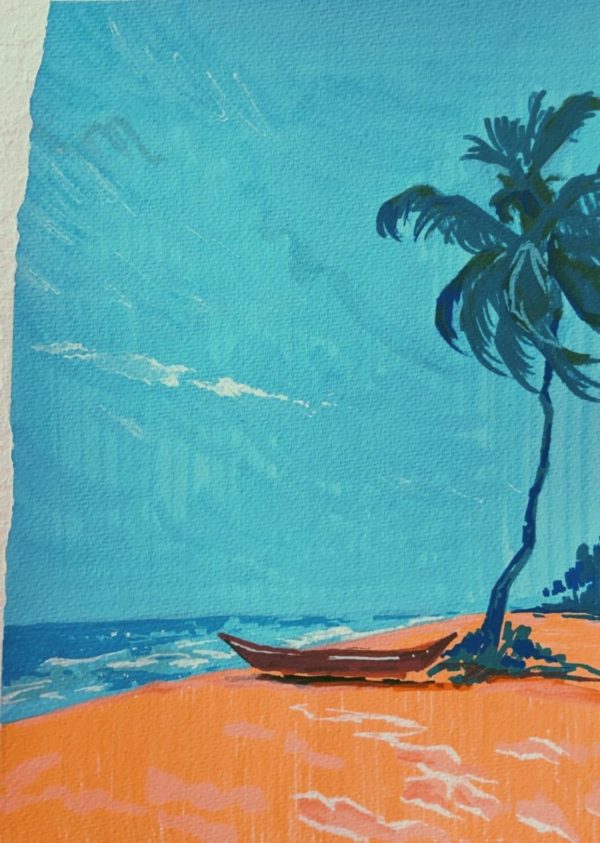

The fishermen themselves dared not transgress the slope that the waves had carved into the beach. They cast an enormous net into the ocean and spent all day retracting it by its long, ropey umbilical cord, their bare feet never leaving the sand. But sometimes the Americans or the French or the Nigerians or the Turks emerged from their respective embassies to brave la Cabane du Pêcheur, a beachfront restaurant with more outside than inside, to get a good look at that coastline they’d heard about. Pygmy goats with nascent horns nuzzled the trash sprinkled in the brush flanking la Cabane, and orange-colored wild dogs with pink, swollen teats stood resolute beneath the palm trees, panting delicately. They trained their eyes, slits and circles, on the strangers munching on bowls of roasted cashews, brushing flies off the sticky bottle mouths of their Castels, and burning their pale soles red on the bleached sand. A man riding a skeletal, bone-colored horse approached and offered them a ride for a few hundred CFA. With no takers, the horse plodded on, leaving soft, crescent moon-shaped indentations in the damp sand that faded under the rush of the tide.

The visitors took to the waves, laughing and splashing with an electrified kind of curiosity. Little girls with pink-purple headscarves and no French to speak of sat on the cliff of the sand dune and watched them with dark, somber eyes, careful not to touch the water themselves. Then the sun sank, and the visitors retreated back to la Cabane, having enjoyed their taste of adventure for the day.

At night, the tourists disappeared and the mélange of French, English and Yoruba faded, but the sound of the crashing waves still echoed over the sand and made the palm fronds shiver. It rolled like distant thunder across le Boulevard de la Mer where putt-putting, two-wheeled zémidjans careened past. It thrummed in the cavernous access center of l’Ambassade des Etats Unis d’Amérique where bleary-eyed members of the Local Guard Force stood watch through the night for car bombs. It finally seeped into the lobby of the chancery itself and dissipated into a soft slush that kissed the glass covering the face of the Marine in the security booth.

Sgt. Beckett didn’t look up. The whisper subsided back into the ocean with a hiss.

“Jack Bauer, I have you loud and clear. How me?” she said.

It was the last radio check of a long night, otherwise she might have snorted into the mic. She was not in fact speaking to Jack Bauer. She’d heard a lot of codenames in her two years as a Marine Security Guard, first with the Sarajevo detachment, then the consulate in Chengdu. But an ambassador, the president-appointed Chief of Mission to the Democratic Republic of Laku, asking her to address him once a week as Jack Bauer was a first. Sometimes Sgt. Beckett was unsure if she was running comm checks or a phone sex service.

The Ambo replied that all was well on his end and disconnected with a burst of static. Beckett exhaled slightly. It had been a dull night monitoring the cameras, remotely opening the maglock doors and politely redirecting calls from people asking for visas in broken English. Laku certainly couldn’t hold a candle to Sarajevo or even Chengdu. It was a small place, the kind of landmass you learn the name of once for a middle school geography test and deftly purge from your mind later. But every embassy, no matter how small, got a detachment of Marines to defend it.

As Beckett marked the Ambo accounted for, she heard the maglock door behind her open with a whoosh. LCpl Parris slogged into the tiny box of a room dressed in his service khakis. His freshly buzzed hair was wet from a shower, and it had dampened the edge of his dark green cap.

“Morning,” he said. The fatigue in his voice emphasized the drawl of his accent, making it sound like the back of his mouth was as wide as the bed of an F-150.

Beckett checked the clock. 0542. “You’re early,” she said.

He shrugged and mumbled something about melatonin. She looked at his reflection in the window closely. Laku was his first assignment, and he’d arrived only a month before. Beckett had learned long ago not to ask about homesickness, but she made a mental note to drag him to the gym with her later. Dips and Drake could do wonders for the spirit in her experience.

Beckett knuckle bumped him on the shoulder as she turned to leave. “There’s half a Monster in the mini-fridge. Good luck, bud.”

He positioned himself in front of the monitors under the smiling photographs of the Ambassador and Deputy Chief of Mission and gave her a stoic thumbs up. She loved that kid. He made her want to build a porch just so he could rock a chair on it.

“Beck?” he said as her fingers closed over the handle of the maglock.

“Yeah?” She was already thinking about drawing her blackout curtains and maybe popping some melatonin herself.

“Is there a drill today?”

Beckett paused, thoughts of sleep draining from her mind. It was Tuesday, and drills were always scheduled on Wednesday. However, when they least expected it, the Regional Security Officer had been known to pay the LGFs to climb the walls so the Marines could practice corralling an intruder. Once he’d slipped the USAID interns the keys to the gardener’s golf cart and made the Marines chase them all over the compound while the students gleefully blasted the Mario Kart theme.

She joined Parris at the monitor he indicated, hoping he’d made a mistake. Maybe it was just another rising junior who’d been rustled out of bed and handed a rubber gun to rob the detachment of yet more sleep.

On the pixelated screen of the monitor, she could make out a man pacing agitatedly near the south wall. Was he just drunk? He probably wasn’t high — drugs were an out-of-reach expense for most here. He was soon joined by another man. Then there were four people. Then an entire crowd was pressing against the wall of the compound. They crashed against it like a flood, arms raised in fists. As Beckett watched, one threw an object over the top that spun round and round before smashing onto the manicured grass — a bottle spitting fire.

People in white button downs and brown pants, the LGFs, were sprinting across the other screens. It was disorienting to watch as a man disappeared on one screen to reappear on the far left. The phone on the desk began to ring like a church bell in a thunderstorm.

Beckett didn’t even bother to pick it up. “Hit the alarm,” she ordered Parris.

He did so, and the undulating tone echoed throughout the embassy, shrill and unignorable.

“You’re on,” she said.

Parris nodded and swept the excess papers off the desk in one fluid motion. He took up a pen, preparing to take down information. Meanwhile, Beckett slung on the vest hung from the hook in the corner and buckled a helmet under her chin. The alarm meant the Marines would get suited up and break hatch, and everyone else would, in the words of Lance Corporal Von Engel, “Stay fucking put or I swear to Jesus H. Christ…”

Beckett tore open the envelope stashed in the filing cabinet that revealed the combination to the gun safe. She fiddled with the lock until it opened and slung an M4 over her vest. Parris eyed her and then turned back to the monitors. She thought she heard him mumble, “If I’d waited 15 minutes” under his breath.

To be a true-blooded American hero. It was in the job description, but rarely was there such an opportunity to earn it.

Beckett tore open the maglock door and sprinted into the atrium. She took three flights of stairs two at a time until she burst onto the roof. Von Engel was already there on the southwest corner, reading a sit-rep into his radio. His sunglasses glinted under his helmet as she joined him. Von repeated his report for her and then added, “Probably another ‘I hate America thing.’”

“You think so?”

The crowd was rapidly multiplying and pressing up against the wall. Signs and banners, too distant to read, cropped up like cardboard flowers, and two more flaming bottles landed in the grass and fizzled.

Von shrugged. “It’ll pass.”

Despite his casual manner, she could tell he was buzzing with excitement. Von Engel was a man who loved three things in life: the military-industrial complex, his Boston terrier back home in Indiana and his Juul. He did not reserve tenderness for much else. Beckett remembered one night when they had invited the interns to the Marine Residence located across from the chancery on the compound. “Like a super nice frat,” the interns observed, except with a well-stocked gun safe.

As Von Engel was lining up a shot, Miguel, an intern from some liberal arts school in Connecticut, asked him why he had enlisted. “Because I wanted to kill people,” Von responded bluntly. He sunk two stripes in opposite pockets, and poor Miguel didn’t speak for the rest of the night.

Beckett had smiled to herself. It was the line that they had all learned to say as a joke, as a cover for whatever pain, or exasperation, they’d rather not share. She knew, thanks to last year’s Fourth of July turning into a sloppy rager after the dignitaries left, that Von was there because his mom died in Enduring Freedom. He knew she was there because it was her way out.

Beckett’s hometown was seeded in that part of the South where God is widely known to show His favor with the gift of McMansions and His disapproval with Supercuts hair styled with an opioid addiction. Mr. and Mrs. Beckett weren’t divorced, but Emily thought they should have been. She and her older brother Dylan had learned as children to make themselves scarce on Monday nights if their father’s team lost. Unless they wanted an earful of the bickering blowout that would follow, rekindled by the loss but caused by nasty tempers and reinforced powerlessness that years near the bottom had fomented.

The Craig’s List playset in the backyard was their fortress. They migrated there, rain or shine, by unspoken agreement. When they were little, Dylan would push her on the swing or they’d play Egyptian Rats under the striped tarpaulin. One year, Dylan declared swinging childish and card games geriatric. They sat in silence a while, before he pulled a pack of Marlboros out of his sock and, making sure she was watching, casually lit one. For the few months he was at community college, she had sat on the swing set alone on Monday nights, twisting around with her toes dug in the dirt. When he moved back in carrying the scent of grease or dust whatever his alternative to school happened to smell like, he’d forsaken their spot and preferred to exacerbate the Monday argument with a few snide comments before sliding into a friend’s car that rolled up and never stopped long enough for her to see who was driving.

It was why she did not expect to see him there that evening. Fall was rolling in and with it a wet chill that cut through her hoodie and frosted the metal playset. Emily was standing beneath the bar holding up the swings and eyeing it apprehensively. She curled her fingers around it and, with a little hop, tried to pull herself up, but to no avail. She dropped with a grunt. Emily looked down at her legs that seemed even scrawnier than they were in the too big, hand-me-down jeans. How could she be so skinny and yet so heavy?

She tried a dozen or so more times and was staring at the tiny, red callouses beginning to pop up on her hands when the screen back door slammed. She looked up to see Dylan striding across the scrub grass.

“Emmy,” a sugar sweet cheeriness laced his voice. “Are you doing pull ups?”

Emily’s heart sank as Dylan reached the playset. He grabbed the chain of the swing in his fist and leaned against it. “Whatever for?” he asked.

“There’s a test…”

His eyes darkened and then became, if possible, even more gleeful than before. “Oh my God,” he said. “Are you going to… enlist?”

She wiped the flakes of paint stuck to her palms on her jeans and said nothing.

“They’ll own you,” he said. “Send you wherever, whenever. You have to do everything you’re told no matter what. And you’re a girl, so they’ll probably post your nudes on Facebook, too. But that’s just what a buddy of mine said.”

Again, saying nothing seemed like the best course of action.

“Get up on the bar,” he said suddenly. “You can’t do a pull up, but you can do a chin hang, surely.”

Deciding it was less painful to just get it over with than make an excuse, Emily once more curled her fingers around the bar and jumped. Her legs seesawed back and forth a moment before she could hold them steady. Already her heart was beating faster and her hands shook, but she endeavored to keep her face completely devoid of discomfort even as pain was lancing down her back. She held it as long as she could, willing herself to be strong, but it was too much. She dropped with a crunch onto the shriveled leaves, and pain shot through her ankle ligament. She hopped a little as surreptitiously as she could until it subsided.

Dylan whistled through his teeth. “Twenty-six seconds. Well. It was a nice try.” He tugged her braid as he left. “My little sister, the killer.”

Emily bit back tears as the screen door slammed again. Once more, she curled her fingers around the bar. Staring up at her fists raised against the white sky, the metal driving a harsh boundary across the clouds, she pulled. Her knuckles were so white the bones appeared to burst through the skin, but she kept pulling.

She didn’t raise herself up that day or the day after. She started by just hanging until she surpassed 60 seconds, then she did pull ups with her mother’s infomercial resistance bands looped around her knees. Even as the metal rod iced over, and she landed past her ankles in snow, she kept her place beneath the bar.

She’d known after the first day she’d been brave enough to walk into the recruitment center on her way to school: This was her way out. There was no way she could pay for college, not without loans, and she’d seen what debt did to people. But it was more than the temptation of the GI Bill. To have her Supercuts hair in a bun and her jeans swapped for a uniform identical to everyone else’s. To be where hard work directly correlated with respect and nothing, not rank, money, nor respect could be inherited, only earned.

It was on the first bright day of the new year, when the sun fools one into thinking it’s warm, that Emily once more took a deep breath and pulled hard with her eyes squeezed shut. After a moment, she opened them and looked down. Her chin had cleared the bar. With a gasp, she released her grip and landed on her feet, but her treacherous legs collapsed and she curled over on her knees. Shuddering on the snow-covered ground, not from cold, but from the spasms in her back. There was perhaps a tear or two also, but the air was too frigid for that nonsense.

Many months later, still wrecked mentally and physically from her last test, the Crucible, Beckett’s eyes hunted through the crowd for him. She found her parents, an empty seat between them despite the packed stands, but no Dylan. It didn’t matter. She squeezed the medallion the drill instructor had given her in her callous covered palm. She’d gotten out.

Even when the nights in Post One were long, or she got food poisoning eating something dodgy from the Port, or she was once again uprooted and sent to a new country, she thought, I got out I got out I got out. Every drop of sweat, every blister had paid off. Every ounce of effort had been rewarded. It was a fair trade, and she’d make it again.

“I bet they’ll try to climb.”

It was still pitch dark, but the chill of the night was beginning to lift slightly. The protesters were coming at the wall and clawing at it, as if tempted to scale it.

“When they know the legendary Von Engel is waiting for them on the other side?” Beckett asked.

“That guy,” he pointed to a man who was kicking the wall and shouting with particular ferocity. “I bet he’s gonna do it.”

It was less Von Engel’s tone of voice and more his grasping at the possibility that made Beckett wonder if he even saw Lakulese protesters at all. Whenever they drove north to the firing range, she always suspected he was seeing whoever had set the ERP that blew up his mom’s convoy. They’d all lost friends, but the possibility of death, suffering it or dealing it, had always been more real to Von Engel than most.

No matter what Dylan said, the day she had decided to enlist, killing hadn’t much come into Beckett’s mind. Even shooting a bullet ripping through a paper target or stabbing a bayonet into a football-like dummy hadn’t felt real, but the urgency and importance of their mission had been deeply ingrained in them. Now she was seeing parts of the world her classmates couldn’t pinpoint on a map, but it had always been clear that the cultural immersion part of the foreign service was for the Ambo, the FSOs, the interns. It was their job to go out into the world. It was her job to keep the world out.

“Don’t bet, Von,” said Beckett dispassionately. It was easier to talk about inane things. Like doodling in class, it kept her mind focused on the situation at hand. “You know what happens when you bet. Take pool for instance.”

Von Engel wouldn’t take his eyes off the protesters to glare at her, but she suspected he wanted to. Von Engel regularly challenged her to pool but had yet to defeat her. He would gab about angles and ricochets, but to Beckett it was a simple game. She only had to care about her side. In a single shot, you could create as much chaos for the solids as you wanted, but it didn’t matter as long as she sunk her stripes.

Beckett shifted her gun strap and rolled her shoulders.

“Antsy, Sergeant?” Von Engel asked

“Just sore,” she replied.

“You do the Murph yesterday?”

She had gotten exercise, but not the Murph challenge. Something that made her sore as she hadn’t been in well over three years. And though she tried not to think on it, it had strained her peace of mind, too.

It had taken Todd, the ambassador’s husband, some persuading to get her to go out with him yesterday, not to mention even the thought of using her mangled French in public made Beckett nauseous. But relaxing at Bruster’s for the afternoon was too good to resist, even if Miguel did invite himself right before they left. Bruster’s was an expat haunt by an inland lake. She’d mostly spent the afternoon sitting on the dock and watching the French nationals splash around. Their light-colored skin under the brown water made it look like they were swimming in Coca-Cola. She wore an oversized puffy white shirt that had belonged to her father over a pair of beige mini shorts that she would not have dared wear anywhere outside an expat haunt. She enjoyed the slipping by of Africa time and the nipping gnaw in her stomach as they waited for lunch with her ankles crossed over the water.

When the French pursued their errant beach ball far enough away for the water to settle, she caught a glimpse of her reflection. With her white oversized shirt and beige shorts, she brought to mind a Kennedy taking the sun. Beckett stood up quickly and went to look for Todd to inquire about lunch, careful to scuttle the image with the tip of her toe as she went.

They ate fish beneath the canopy before catching the puttering boat back through the tunnel of mangroves to Todd’s car. The engine and his Bob Dylan CD rumbled to life at the same time, and they took off down the road bordering the beach. After a few minutes of knock, knock, knockin’ on Heaven’s door, Miguel tapped a finger on the window. “What’s that, Todd?”

Beckett looked up from her book. At first, she thought he was asking about the man under a tree hacking a coconut with a machete or the other man wandering past who was prattling about his wares, a stack of branded baseball caps, in Fon. But these were ordinary enough sights for the beach road, especially as they got closer to La Cabane.

“The horse?” she asked, indicating a man sitting on a ghostly animal who was chatting with some vastly disinterested beach goers before an audience of girls in pink headscarves.

“Nah, farther,” Miguel said.

Beckett and Todd looked, and she saw what had interested him. Down the beach, there was a long line of people swaying. They were pulling on an enormous rope that wove through maybe 60 of them and disappeared into the waves. The other end squeezed the life out of a tree trunk like it was a pulley. As the car rumbled closer, she could see each had a T-shirt wrapped around the rope underneath their grip. They swayed back and forth as they pulled to the music of a man picking out a dancing beat on an empty oil drum tied around his neck with a length of twine.

“They’re fishing. It’s a net,” said Todd.

“A net?”

“Look down the beach, all the way down there. See that other line of people? They’ve got the other end of it. By this evening maybe, they’ll have come together and got it out of the ocean.”

Beckett strained her eyes. So far down the beach as to be almost out of sight was another line swaying against the horizon.

“But evening’s still hours away,” cried Miguel.

“You want to see?” Todd asked, already pulling the car over. He seemed at once encouraging and resigned. “You can go pull with them. They’ll let you.”

Miguel flung open the door eagerly, and a moment later, Beckett followed. She felt the hot sand fill the gaps between her toes and her Chacos and the sea wind push under her shirt. The fishermen were very welcoming, especially to Todd who was muscled and well over six feet. They made room for them at different points on the rope, and Beckett looped her bandana on the rope before wrapping her calloused hands around it. Holding the rope was like holding a snake that continually wanted to spring out of your hands. It was very thick; her fingers and thumbs couldn’t meet. She trained every day and never scored below first class on her fitness test, but still, it was hard work. The sun was in her eyes, and they were far from the cooling sea spray. Nevertheless, she gave it all she had, focusing her eyes on the back of the man’s head in front of her and swaying to the dancing rhythm.

Though she started near to the ocean, in what seemed like an hour, she found herself near the tree line though there was no discernible change in the rope, nor sight of a net. Before she could rotate down to the beginning again, she noticed Todd and Miguel waving her over. Forcing down her misgivings, she dropped the rope, nodded at the fishermen and followed them back to the car.

Miguel reached past the sergeant sitting in shotgun to turn on the AC and declared he was inspired to join the Peace Corps.

As Todd started the car, Beckett rolled her tight shoulders and asked, “How much will they get once they pull it in?”

Todd considered. “It might fill the trunk of my jeep.”

Beckett froze and gaped at him. “All day, they’re pulling. And that’s all?” Todd nodded. His fingers tapped on the steering wheel. His mind seemed to have drifted outside the car.

“They can’t do something else?”

Todd looked at her and then at the concrete skeletons of unfinished buildings and helmetless zémidjans zooming around. “Like what?”

Beckett had no answer. The conversation fell back into silence and Bob Dylan.

“You know I’m not an officer, just a hubby, right, Emily?” Todd asked suddenly. “So what I say isn’t real and doesn’t matter one titch.”

She scanned his tan profile and nodded.

“His excellency, the President of Laku, has been in power 16 years at this point. Given that he always wins with 98 percent of the popular vote, or higher, I’d say the results this morning are a given.”

“Are you talking about the elections today?” asked Miguel. He leaned forward in between their seats, scrolling through his feed on his phone. “I saw on Twitter that they’re about to call it for the incumbent. Did you know he and his inner circle account for about 30 percent of the wealth in this country? All that oil money. I heard the challenger, what’s-his-name, the neo-communist, wants to nationalize it. Get some redistribution going.”

“That ‘neo-communist’ is also more willing to accept aid and technology from a certain great power, not the US,” said Todd.

Beckett leaned down to pick her book up off the weather mat to gain a respite from Miguel’s fish breath. “What are you saying?” Beckett asked Todd finally.

“The elections. The voting. Everything that’s already happened or might happen later when they’re tallying up…” Todd turned the car onto le Boulevard de la Mer. The wheels ceased their bumping and continued smoothly on the paved road. “I’m definitely not saying we helped. But maybe I’m saying we knew, and maybe we could have done — or said — something about it, and maybe we didn’t. And if that were true, man, it would really eat me up and make me want to get away for the day.”

Beckett cast around for something to say to fill the silence. “It’s not our job to make the world fair,” she said finally. Todd nodded, in a casual, swaying motion. He adjusted the rearview mirror. “You met the president’s son, didn’t you, Miguel?”

“Yeah, with Parris and Von and the others at Code Bar a few weeks back. He wanted to do a lot of shots with us. Tequila, Tambour…” said Miguel. He leaned back against his seat and was quiet for a minute, deliberately absorbed in his phone. “I heard him say to Parris, ‘My ancestor got rich selling your ancestors into slavery.’”

No one seemed to know quite what to say. Beckett opened her book, but the words crawled around on the page like ants. She tried looking out the window instead. Now that she had seen the rope carve grooves into the trees with the force of the fishermen’s pulling, she couldn’t stop noticing the scarred trunks all the way back to the embassy. They rose out of the sand everywhere Beckett looked. She bet her old classmates’ parents would pay their interior designers a lot of money for one. She imagined a swarm of mid-career professionals armed with Alex & Ani bracelets and ramen-colored balayages harvesting the art like a swarm of locusts so fast that the trees just disappeared. The rope with nothing to hold it, snapped back on the fishermen and knocked them into the sand. Boing!

Todd parked the car in the embassy lot. Beckett thanked him for lunch and then tried and failed to cache some sleep before her 2200 shift started. She doubted her fatigue would matter. Nothing ever happened at night.

The next morning, the crowd had grown to the point where it spread into the street. From the roof, she could hear the mob take up a chant, a word that they bellowed into the morning mist. A floodlight flashed over the signs, and her burgeoning suspicion was confirmed.

“It’s not ‘everything’ they’re angry at us for, Von. It’s the elections.”

“So sore losers.”

“Must be.”

“I mean, the guy whose name they’re chanting, he’s basically a communist, right? So no loss.” Von put the radio to his lips as he prepared to make another report to Post One.

“If you mean he’s planning to ‘get some redistribution going,’ I guess, yeah.”

Something in her tone must have momentarily diverted Von’s attention. He paused and moved the radio away from his mouth and looked at her sidelong, his face unreadable under the helmet and sunglasses. “Sergeant. Respectfully, get your head in the game.”

The game? For a mad moment, Beckett thought he was talking about pool again. But this was her job. This was what she was here for. It was how she had gotten out.

Her mind spun like a dial and landed familiarly on her training. Her eyesight hopped from roof to grass and landed on the wall in time to see two arms and then a head appeared on top of it. A protester had started to climb and might even try to come in.

Sgt. Beckett knew the rules of engagement like the back of her hand. He wasn’t theirs, hers and Von Engel’s, to deal with. Not unless he was armed. She hoped to God he wasn’t armed.

The man pushed himself up on the wall and swung his legs over. He dropped like a stone to the ground. Von began speaking rapidly into his radio, but Beckett didn’t hear a word. Everything felt unreal from their perch, staring into the patchwork darkness and floodlight with nothing to touch them but the wind.

“Sergeant.”

One shot. One shot focused on sinking her quarry. The ricochets, the collisions, the ensuing chaos on the table didn’t matter. That was just the game. Wasn’t it?

Beckett got low on the edge of the roof like it was the table and shouldered her gun, reminded irresistibly of a pool cue. She trained her sights on the man below. He was staring down one of the other Marines and a few LGFs who had run out to detain him. Something metal flashed in his hands.

It was a gun; it had to be. Her finger, near rigid with tension, cradled the trigger. She put the scope to her eye.

In doing so, she caught a glimpse of light in the distance, far away from the floodlights of the compound. As she watched, transfixed, the sun crested the horizon over the ocean. In its glow, she could just make out a long, skinny line of people traversing the sand, swaying to the beat of an oil can ticking away forever. Holding on tight day after day as though trying to tame the sea.

In a flash, the blue sea became the sky, the rope, a cold bar traversing it. She was 17 again, a girl in her scrub grass backyard trying again and again to pull herself up on an old playset. She could hear shouting in the distance. Her parents — no, the crowd amassing outside the gates.

I got out I got out I got out

“Beckett!

A 100-plus men and their families struggling to pull a net out of the ocean halfway across the world. She had gotten out. How could they ever?

“Emily!”

Dylan?

“Take the shot, Sergeant!”

The scope shuddered against her eye socket. Her hands — her hands were shaking. She crushed the gun into her shoulder and tasted copper in her mouth. She harbored a prayer, a bargain in her heart. Only if he got too close, only if he started shooting, only if it actually was a gun then—

BANG

Beckett instinctively clapped a hand to her ringing right ear. She smelled smoke on the wind, coiling from the barrel of Von Engel’s gun.

When she looked down her scope again, she could see a dark mass on the ground where the man had been. He was still.

With an ear-splitting roar, the wave crested the wall and crashed onto the sovereign soil.