Giovanna Truong

When I tell people where I am from, I tell them “New York City.” If they are a New Yorker or if they are familiar with the city, I tell them the edge of Queens; if they know Queens well, I tell them the Bayside area; and if they are Queens natives, I finally tell them Little Neck. My general answer in college has been, “I live on the edge of New York City, but I went to school in Manhattan.” I am quick to attach the latter clause. Most people do not think of suburbia when they hear New York City. They think of Manhattan — skyscrapers, mustard yellow taxis, Broadway and crowded streets of people in everything from business attire to absolutely no clothes at all. During my childhood, my family went to Manhattan on weekends once or twice a year. In classic tourist fashion, we only ever went to and took pictures at Times Square.

My home, however, has always been Little Neck, which is next to Great Neck, where F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby” takes place. I realized only that the book took place so near my home when I opened up to a map included in the beginning of this edition of the novel. It took me a few seconds to realize that “West Egg” was Great Neck, that one could walk to Fitzgerald’s former home from my home in 10 minutes, that staring at me, in the preface of this renowned American novel, was Little Neck, my small, obscure hometown.

Little Neck is a relatively unknown part of New York City, but at its core, it is a suburb, a place and idea that Americans know very well. My parents immigrated to Little Neck from Korea in 2001, a year before I was born. Until I was six, we lived in a small apartment next to the Little Neck Long Island Railroad, or LIRR, station. My parents had a lot of trouble in that apartment: The train blared twice an hour, the landlord charged them fees that he was supposed to cover and mice lived in the thin and crumbling walls. In 2006, we moved to the house that we’ve lived in for the past 14 years. The two-story white brick house sits at the top of an inclined street next to other white or red brick houses that look just like mine, all with the same tiled roofs and wide-eyed windows. Cars occupy every potential parking space because everyone has their parking space. It’s rude to take someone else’s. There is a one-story house near the bottom of the street with a Cadillac Escalade parked in its driveway. I have always noticed it — its eggshell radiance, the sheer mass of its presence — because my father used to say to me that his dream was to buy a Cadillac Escalade, but that the people down the street were bastards because they left it still in the sidewalk instead of fully in their driveway. At the very end of the street, a very big Labrador lives in a one-story house, and he barks and aggressively gallops toward me every time I walk by. My sister says that that dog once jumped over the fence and chased her up the street. The other dog in the neighborhood who hates me is Coco, my downstairs neighbors’ shrieky brown dog the size of a purse, who, without fail, comes to the window and shrieks at me every time I am at the door.

Many of the residents of Little Neck are immigrants, most of whom are Asian. We do not talk to one another. Not many people speak English fluently, so aside from the occasional hello passing by one another, in Little Neck, the immigrants can rest their tongues from the workout of English. The only time we ever talk to our neighbors is when we have to divide shoveling labor after a snowstorm or when renters have to ask the homeowners to fix a door or a pipe. The only reminders the residents of Little Neck have that their neighbors exist are when they make a ruckus. The sound made when you close a window is enough to let your neighbors know that they are being too loud. This past summer, my parents shut their windows in the early evenings to block out the traditional Chinese music that an elderly Chinese woman blasted for her nightly stretch and dance sessions with her girlfriends. After 10 p.m., we shut windows because of the cackling of the Italian family next door having gatherings with friends.

Little Neck also has a significant population of elderly white folk, many of whom sit with each other on front porches in the early evenings. One day after school in the fourth grade, an elderly lady sitting outside a chestnut brown, ivy-covered house in the middle of the street struck up a conversation with me and my mother. I was worried that this elderly lady might be racist and yell at my mother, and by extension, me. “Go back to your country” or “speak better English” — something along those lines. Instead, she shared her life story with us, strangers. Her husband had built the house, and he’d died a few years before. After this conversation, we never saw her again, and a few years later, the home was torn down and replaced with a two-story house.

***

My love for Manhattan sprouted concurrently with my dislike for Little Neck. It began in the seventh grade when I started attending my new school on the Upper East Side.

“Manhattan is a grid, so you can get anywhere if you know the street and avenue.”

“Megan and I live in the same apartment building.”

“You’ve never been to the Met?”

These concepts were foreign to me. Queens is the largest borough of New York City in terms of land mass, and its street system is convoluted and disorganized. Little Neck has houses, not apartments, and it didn’t have world-renowned tourist attractions. The idea that you could live so close to your friends was, in particular, astonishing to me. I had always been jealous of the characters I saw on television who were friends with their neighbors; now, I was jealous of the kids who lived in Manhattan.

I didn’t have much mobility growing up in Little Neck. My parents never trusted me to go anywhere on my own, so I always traveled with one of them. Even the nearest park was mostly off-limits because my mother never wanted to walk me there when I asked. Constrained by my parents’ unwillingness to accompany my travel requests, I spent most of my time indoors. But even without my parents’ protective umbrella over me, I didn’t have much of a reason to travel. All my friends from school lived at least 10 minutes away by car, and I had no friends in my neighborhood to whom I could walk within a few minutes.

I started taking the LIRR every day in the seventh grade to commute to my new school in Manhattan, and with my ticket for unlimited monthly rides came more mobility than I had ever had. I quickly realized, however, that my newfound mobility paled in comparison to the freedom my Manhattan peers had enjoyed their entire lives. Manhattan kids could walk anywhere they wanted and know exactly where they were going. Manhattan kids lived a floor above their best friends, and Manhattan kids were never bored. In Manhattan, there is a Hungarian Pastry Shop, a Central Park, a Whitney Museum, a Hudson River to satiate your every need.

Throughout high school, if I ever wanted to escape home and do something fun, I’d commute to Manhattan. Since Little Neck offered me nothing, I left it as often as I could. And when I came home, I always noticed how quiet Little Neck was in comparison to the bustling city. Everything moved in Manhattan — its people, its lights, the latest fashion trends and the newest Broadway shows — and I loved it. I saw Little Neck’s silence, thus, as the absence of life, a snow globe where nothing changed besides the wrinkles on its residents’ faces.

Manhattan meant liberation. Manhattan was where I could do anything and everything without my parents watching and being a part of my every move. While my parents were experts on the streets of Queens after over a decade of driving, they knew much less about the nitty-gritty of Manhattan: how quickly to walk in the streets, what kinds of apartments people lived in, how far people walked to get from place to place. They were shocked whenever I told them I had walked from 72nd Street to 116th Street. Trips to Manhattan were still vacations to them, and Manhattan was an impossible metropolis where we could live only if we won the lottery.

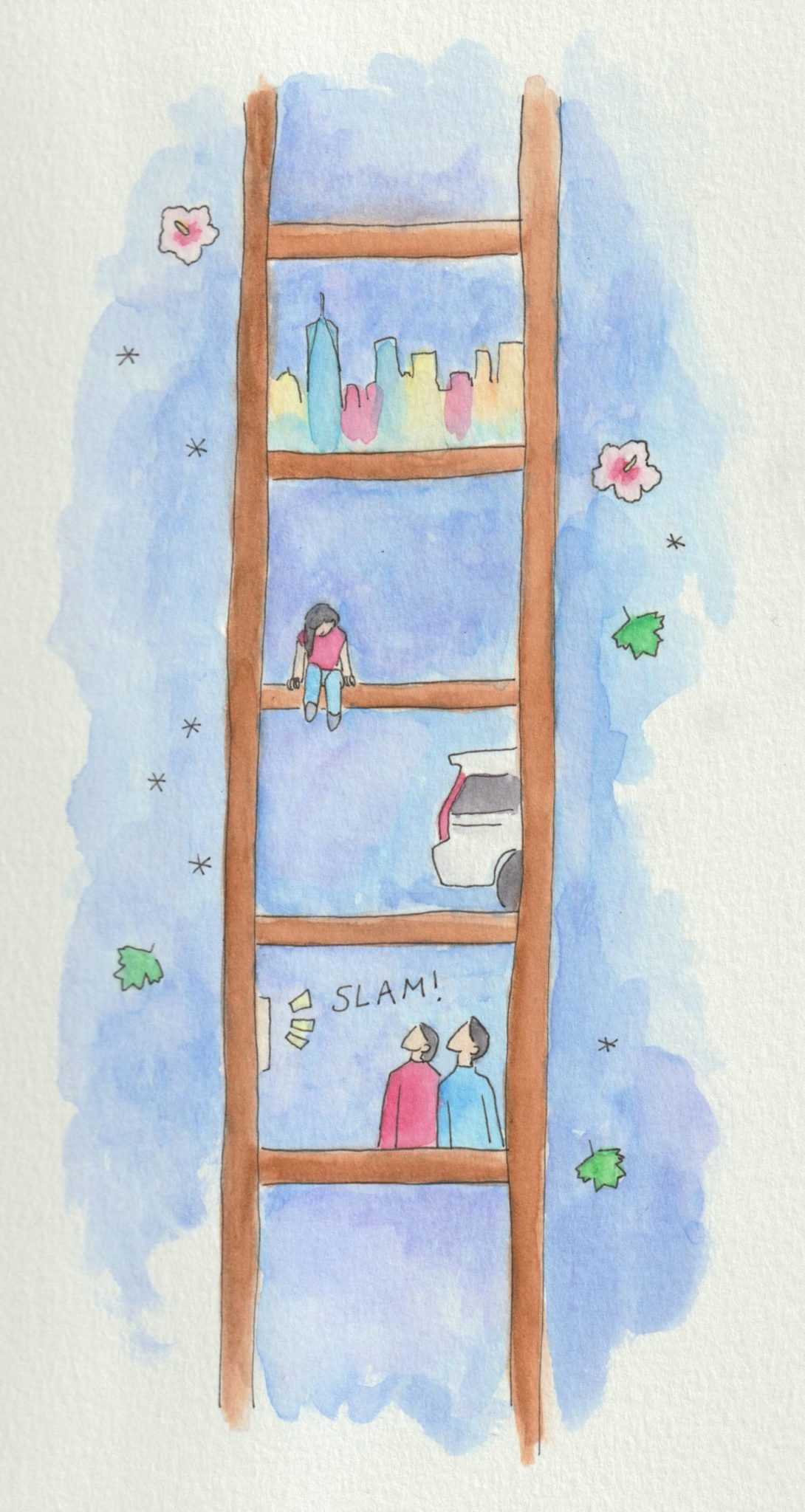

While I feared racism from elderly white people in Little Neck, I walked confidently in the streets of Manhattan, where my interactions with people were solely defined by my good English instead of my parents’ broken tongues. Additionally, my presence in Manhattan, this place of wealth and extravagance, signified mobility, a sign that I was already living a better life than either of my parents. Little Neck was the rung of the immigrant ladder my parents were stuck on — like an English word their Korean tongues could not stop stuttering on — that I needed to escape. Manhattan was mine. I was in love with the dream Manhattan enveloped me in, the affair it enticed me to indulge in, to break off my loveless, unhappy marriage with Little Neck.

***

When my parents moved to America, they still owned an apartment in Korea. Though I’d wondered why they didn’t sell it, I always assumed that they planned on staying in America. My mother frequently told me in my childhood that one of her greatest desires was to own a home, and since she owned a home in Korea, I thought she wanted one in America. And one of my father’s favorite hobbies was to surf the web for home sales in the States. I grew up thinking that my home was their home, and that my home would always be their home.

This February, my father asked me and my sister if we wanted to live in Korea for a few years, before I went to and after my sister graduated from college. We both said no. My sister interpreted my father’s asking as a sign that he wants to go back to Korea. I was surprised. It had never occurred to me until this moment that America may not be the end goal for them, that they might want to move back to Korea.

The more I thought about my parents returning to Korea, the more I thought it was a good idea. I thought it’d be ideal for them to be near family and to be able to speak comfortably and fluently with anyone around them. Moreover, each day spent in Little Neck was a day closer to the bed in our house becoming either of my parents’ deathbed. I knew that my parents would want to be buried in Korea when they died, so I didn’t see why they should extend the time they were away from home. I had grown up. They didn’t have to stay for me.

I asked my mother what she planned to do once I left for college. Did she intend to stay in Little Neck? Or did she want to go back to Korea?

“I don’t know. I haven’t thought about it,” she said. “There are a lot of factors to consider.”

I was surprised by this response as well. I had expected more certainty from her, more fervor to live, to not make this rung of the immigrant ladder her last. And I didn’t know whether my mom actually liked Little Neck or whether she was simply too afraid to say goodbye.

I’ve always known that I would leave Little Neck when I grew up. I never imagined myself staying there. My parents came to America to give me an adulthood that did not mirror my childhood. That’s what immigrants do. My new home would be Manhattan, or Brooklyn, or Washington, D.C., or Chicago, or anywhere in California. But not Little Neck.

A month after my conversation with my parents, a pandemic struck and decimated New York City, the city I loved so dearly, and shocked me back into the home I had been trying to escape for six years. My last LIRR ride was on March 13, 2020, the Friday before quarantine began. I got home around midnight after hanging out with a friend on the Upper West Side, my favorite place in Manhattan, and I got off the train without a glance back at my mobility, which I’d be saying goodbye to for an indefinite period of time. I had not realized that the ride would be my last. I had expected to spend the months I had at home before heading off to college in Manhattan with friends. Instead, quarantine brought me back to Little Neck, the place I thought I’d be saying goodbye to forever.

Interestingly, besides people wearing masks on walks, nothing really changed. The elderly folks still sat together in the early evenings to chat. Coco still barked at me whenever I passed by. Streets with tons of space for pedestrians to distance themselves, the quiet of the days and nights, the boredom of it all — in the face of an upheaval of life as I knew it, Little Neck may have been one of the only parts of New York City to remain almost completely intact in its pre-pandemic form. My small, obscure hometown.

Stuck at home, I tried to find mobility within Little Neck. I took walks with my mother and sister frequently, and I also started biking. I used the kid’s bike that my parents had bought for me when I was eight years old, which I had barely used in the past decade. There had been no need. And because of biking, I discovered the full extent of Little Neck’s beauty. There are wide roads flanked by trees, with sunlight outlining each leaf such that they glow together in a sum greater than its parts. There is a green lake hidden next to the former-Fairway-Market-now-turned-Food-Bazaar and contoured by a curving road full of cars. I stopped once next to the now-closed Toys-R-Us and Burger King and gasped at the sight of the vast trees clashing with the apartments and roads of Little Neck. The natural landscape coexisting with commercial buildings and cars. American suburbia captured in one picture.

At some point in quarantine, my father asked at the dinner table if we thought it was a good idea to move to another house. To buy a house in America. My mother was silent. When I was younger, I would’ve immediately and excitedly said yes. Two months ago, I might have asked, “Are you planning on going back to Korea?” But at this moment, I responded, “No, I like this house. I don’t think we need anything more. It’s a good house. It’s a good neighborhood.”

What I truly meant was, “I am afraid to leave. The older I get, the more I become my own person, the less I want to let go of the things that shaped me. The place that raised me. And I love Little Neck. I cannot imagine coming back here and seeing another family live in this house. I cannot imagine Little Neck not being our home.”

In May, my parents took me and my sister to Little Neck Bay to get some fresh air. The rocks next to the water were free to sit on. I had never been here before. Waves crashed into the rocks, and looking out onto the water, across the bay, I could see the faint image of Manhattan’s skyscrapers. The dream. Yet I was happy where I was standing. I wanted to be in Manhattan again in the future, but not for some time. I wanted to bask in Little Neck, in its quiet steadfastness and stillness. I looked to my parents as they gazed at the waters and wondered if they were thinking about their two homes. If they thought they had achieved the dream, if here, in Little Neck, this was living enough. I wondered if they’d return to Korea, and I wondered if I would return to Little Neck.

When I take the LIRR to Manhattan at the end of quarantine, I will forget about Little Neck. I will be lost in the excitement of it all. And when I leave Little Neck for Manhattan or Brooklyn or California, I will proudly tell people the name of my new city when people ask me where I live. But I will remember Little Neck whenever I sit down and talk with a stranger about their life story. I will remember when I hear a neighbor close a window because I am too loud, and I will remember whenever I talk to my parents, wherever they are. I will remember Little Neck, my home.

A few weeks before I left for college, before I left Little Neck, my mother and I stood on our balcony and looked at our street. The setting summer sun coated all of Little Neck in orange light. The elderly people set up shop for their nightly chats, a dog down the street barked at an innocent pedestrian and neighbors silently took out the trash. I told my mother that I had never realized how beautiful Little Neck was until I was stuck here.

She said, “Your father is always looking for other places to live, but I have always liked Little Neck. I was so happy when we got this house.” She paused and then proceeded, “I love this place. Do you?”

“Yes,” I replied. “I do.”