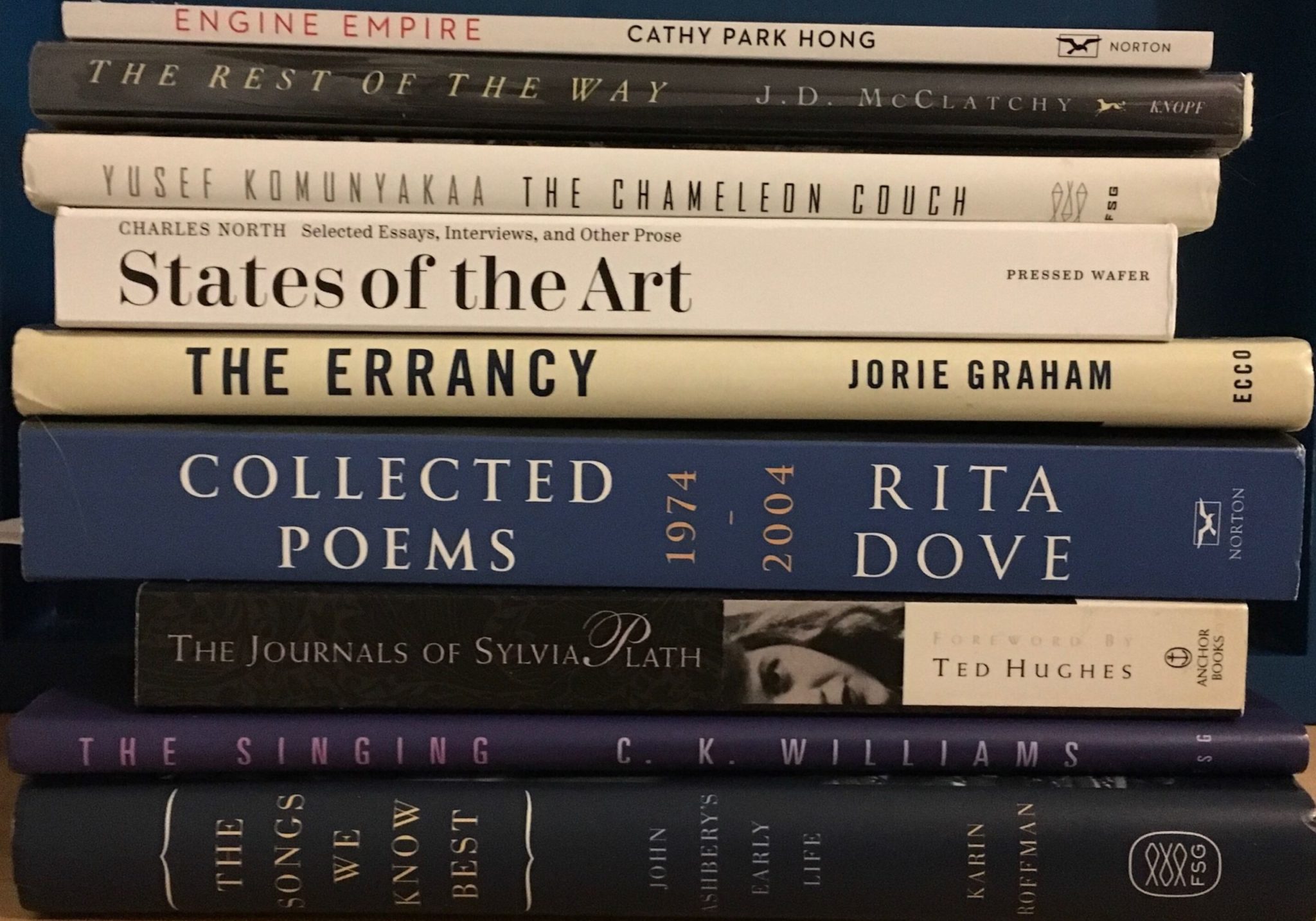

Courtesy of Nancy Kuhl

Although all art is a reflection of its period, poetry can seem especially malleable. Often unrestricted by the conventions of traditional writing, poetry is an organic representation of human experiences, emotions and ideas. At Yale, many students use social media to either read poetry, or post works of their own.

“It has encouraged me to be more honest,” Kiran Masroor ’23 said about her poetry account on Instagram, @poemsbykiran. “I am able to connect with people across the world; it’s the most crazy and wonderful feeling because it’s incredible to imagine that you can have such connection with people through such a simple way.”

Masroor was originally hesitant to share her work on social media platforms. She said that poems she saw on instagram were inspirational, while she prefers pieces that are thematically romantic or “story-like.” Coming to Yale allowed Masroor to see more people expressing their emotions through work on social media. She then began her poetry account, hoping to add a unique voice to the platform.

Nancy Kuhl, Beinecke Curator of Poetry for the Yale Collection of American Literature, said that the publishing history of American poetry is rich and fascinating. Innovation made by American poets, such as Walt Whitman and Emily Dickison, provided a “fertile ground” for later writers.

“Social media platforms add a new layer — allowing poets to reach new audiences around the world and providing a virtual space for the development of dynamic new poetry communities,” Kuhl said.

According to Kuhl, the tradition of American poetry reflects diverse means and technologies for publishing works. Each year, the department she curates adds hundreds of new and recently-published print poetry publications — including books, chapbooks, pamphlets, broadsides, artists books, magazines, zines and other formats.

In addition to her work at Yale, Kuhl is the co-editor of Phylum Pres, a publishing company she owns with her husband, Richard Deming. This company publishes pamphlets and chapbooks of poetry. Kuhl said that publishers — a broad term which can include both large publishing houses and micro presses — often use a mix of standard technologies. These technologies include both new and accessible methods such as desktop publishing as well as historic methods like letterpress printing and hand-sewn bindings.

“Some of the most exciting publishers combine old and new printing and publishing methods to create ultra-modern works that engage with the history of publishing and printing even as they point to its possible futures,” Kuhl said.

However, for many young poets, breaking into the industry is a daunting task.

Lang Leav, international bestselling novelist and poet, began writing poetry in grade school. Drawing inspiration from a poem by American poet Emily Dickinson, Leav filled notebooks with her poems. These notebooks were later passed around the school yard for other students to read her work. Decades later, Leav’s poems went viral on the social media platform Tumblr and she self-published a book called “Love & Misadventure” in 2013.

“I felt as though I was repeating the process I had in the school yard, only on a much bigger scale,” Leav said. “‘Love & Misadventure’ began appearing on bestseller charts, and the publishing world took notice. Within months I was signed up with Writers House in New

York and soon after, published with Andrews McMeel.”

After the success of her book, Leav began posting her work on Instagram where she has now amassed a following of over 500,000.

“Each piece I share online should be viewed as a first draft,” Leav said. “In my opinion time is the best editor. To have an incubation period for your work is the ultimate luxury, and one I certainly did not possess whilst writing under the glare of the social media spotlight.”

Leav reflected that the nature of the internet is a new frontier for poets of her generation, and said they face “uncharted territory.”

Several Yalies are contending with this “uncharted territory.” Leila Jackson ’22, began writing poetry in middle school but picked up writing again this semester.

Jackson has always found poetry to be liberating, While sharing her poetry on Instagram allows her to reach a larger audience beyond her immediate circle, Jackson added that she also feels the loss of a “sense of authority.” She said that when her art is shared with the world in such a public format, she no longer feels complete ownership of her work. “But there is beauty in that as well,” Jackson said.

Leav said that once poetry is out in the world, young poets often fear plagiarization: a sad but unavoidable part of digital platforms. “Talent will always win out in the end. Just remember, you will go on to write better things,” Leav said.

Beyond the experience of poets, some poetry readers prefer more traditional mediums over social media.

Eugenio Garza García ’23, who reads and writes poetry both in Spanish and English, said that the nature of Instagram poetry often means that a reader may not entirely grasp what a poem is trying to achieve.

Garza García, who is also a sports staffer at the News, said that, in his experience, poets often put a lot of thought into the format of the physical copy of a poetry book. When that traditional format is taken away in order to fit a certain ratio on social media, there is often distortion of the poet’s intent.

Riley Soles, ISM fellow and lecturer who teaches Directed Studies literature and poetry courses, said that poetry serves to “destabilize” the structures that exist in readers’ minds. In that way, making poetry from unorthodox, unconventional or marginalized voices is something that should always be encouraged.

Soles added that poems are bigger than the context in which they are encountered and said that a poem is always bigger than what is seen on social media.

Yale professor and poet Louise Glück won the 2020 Nobel Prize in Literature.

Correction, May 7: Eugenio Garza García’s last name is Garza García, not García. The story has been updated.