Courtesy of Wizdom Powell

Putting race at the forefront of a state-wide conversation on healthcare equity was a top priority at a virtual legislative town hall on Wednesday.

Elected state officials and Black faith leaders from across Connecticut gathered over Zoom for the annual Ministerial Health Fellowship Legislative Town Hall. The event — attended by over 100 viewers — discussed legislative priorities under COVID-19, including strategies to resolve healthcare inequality, Connecticut’s Medicaid program for children and caretakers and the necessity of accurate racial and ethnic data in combating COVID-19. It was organised by the Ministerial Health Fellowship Advocacy Coalition, a group composed of Black faith leaders and congregations from across the state dedicated to the elimination of healthcare disparities.

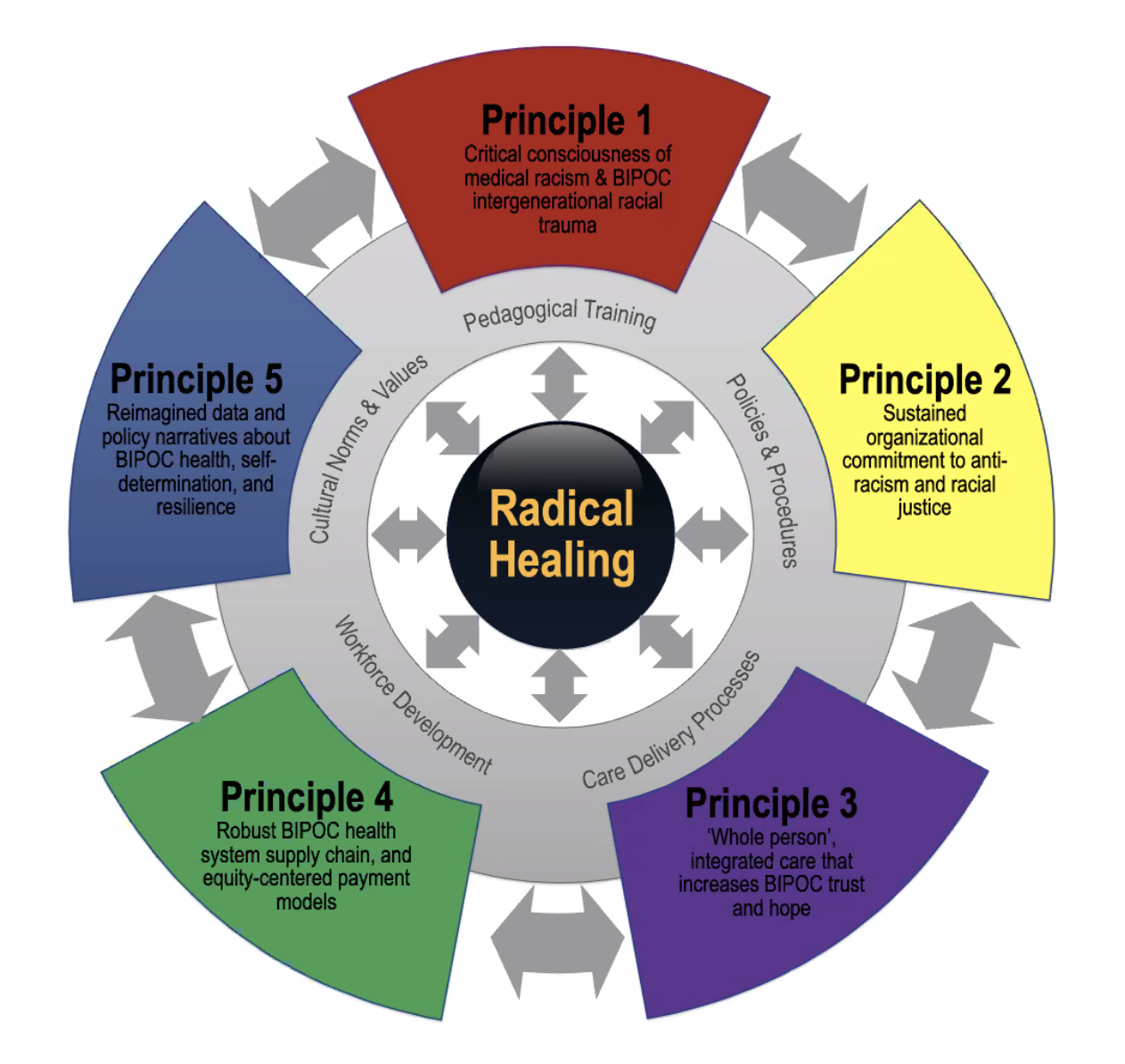

“When we improve equity for those that are most vulnerable, we actually improve the health for the entire population,” said Wizdom Powell, the director of the Health Disparities Institute at UConn Health. “We need a sustained organisational commitment to anti-racism.”

The sustained commitment Powell advocated for is a “Radical Healing Agenda” — which calls on legislators to address the root causes of healthcare inequity rather than coping with its effects. Powell told attendees that the United States’ history of scientific racism is only part of the problem — because medical distrust in the Black community is more closely associated with present-day racism.

Powell is also an associate professor of psychiatry at UConn. She said that the lack of universal mental health care coverage in Connecticut means that it fails to protect young people from traumatic racial incidents. She said that one of UConn Health’s initiatives uses art to create spaces for racial trauma healing and recovery.

“We are treating this challenge around health equity and the eradication of racism as if it is unsolvable,” said Powell. “But racism was man made, therefore, it can be unmade.”

Rev. Robyn Anderson, a pastor and the Director of the Ministerial Health Fellowship led the group in prayer. She also showed a video with testimonials about how COVID-19 has impacted Connecticut residents. In the video, more than 10 people from across the state spoke about job loss, healthcare inequality and other negative impacts caused by the pandemic.

“More vaccines need to be produced so that anyone who wants the vaccine has access to it,” said Nichelle Mullins, President and CEO of the Charter Oak Health Center. “We see Black and Brown people being blamed for bringing the numbers down because they do not want to get the vaccine.”

Mullins noted that the opposite seemed to be true, with many people of color on waitlists to receive the vaccine.

Tekisha Dwan Everette, Executive Director of Health Equity Solutions — a nonprofit in Hartford — also spoke about the parallels between racism and adequate healthcare.

Everette said that collecting race, ethnicity and language data needs to become a legislative priority. According to her, the state of Connecticut’s collection of this data is limited and fragmented. Everett said this makes it difficult to explain welfare and healthcare discrepancies between different racial groups.

“Without this data, inequities may be invisible and we can’t see which policies make them better and which make them worse,” said Everette. “African Americans in every age category were some of the people that got the least amount of vaccines in the distribution.”

Gov. Lamont’s decision to base vaccination distribution on age alone made headlines as some believe individuals with underlying health conditions should be prioritized.

Everette said that Connecticut’s simple vaccination approach may undermine treatment of those in areas with a higher transmission rate or death rate, which are often communities of color.

Health Equity Solutions, Everette explained, has been partnering with local advocates on the ground to declare racism as a public health crisis in Connecticut. She said the nonprofit has requested legislative action from the governor and state legislature.

Keith Grant, a Senior System Director at Infection Prevention Hartford Healthcare also spoke to attendees about legislative efforts for helping those in need. He outlined how education initiatives were offered to those who do not want to take the vaccine. According to Grant, there are also programs in place to contact individuals by phone if they do not have access to the technology needed to book an appointment and provide transportation to testing or vaccination centers.

“There is so much we’re missing,” said Grant. “COVID is an exam that we failed. What scares me is that we can fail again.”

Towards the end of the event, Anderson opened up the floor to questions. Attendees asked about how residents should be treated should they choose not to receive the COVID-19 vaccination.

In response to the question, Mullins said that taking the vaccination is and should be a personal choice. The role of health care providers, she explained, is to ensure people have the correct information to make informed choices.

“This is a conversation about agency: Do I have the right information to make the right choice for me, my family, and my community?” said Mullins. “If you choose not to get the vaccine, continue to wear your mask, continue social distancing … and keep praying because we all need it.”

Douglas McCrory, State Senator representing Hartford, Bloomfield and Windsor, also attended the event.

Melanie Heller | melanie.heller@yale.edu

Natalie Kainz | natalie.kainz@yale.edu