Courtesy of Association of Native Americans at Yale

On Wednesday, members of the Association of Native Americans at Yale convened to recognize the crisis of violence against women in Indigenous communities.

The event, usually held annually on Cross Campus on Feb. 14, moved online due to public health restrictions. This year, members of ANAAY convened privately as a community to grieve and reflect on the crisis before opening the second half of the event to the public. ANAAY also held a raffle to support Indigenous-owned businesses.

“[Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women] is an issue that is not well known by so many non-Native people in the United States, but it affects Native communities and individuals on a devastating scale,” wrote ANAAY co-president Evan Roberts ’23, who is Tlingit, in an email to the News. “Native communities across what is now known as the U.S. and Canada have been dealing with MMIW for centuries.”

According to the Council to Stop Violence Against Native Women, Indigenous women are murdered and assaulted at rates more than 10 times the national average. The growing international MMIW movement has sought to bring recognition to persistent — and underreported — violence against Native women and transgender persons.

And according to the Association of American Universities’ 2019 Campus Climate Survey on Sexual Assault and Misconduct, these disproportionate rates have affected campuses across the country, including Yale. Nearly 50 percent of Native women at Yale have been sexually assaulted while at the University, according to the survey.

“The Association for Native Americans at Yale’s Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women’s (MMIW) event has become a meaningful yearly gathering bringing necessary awareness to an issue that often goes unnoticed,” wrote Native American Cultural Center Dean Matthew Makomenaw, a member of the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians, in an email to the News. “It is imperative that we provide occasions for people to gather virtually and build community to the best of our ability.”

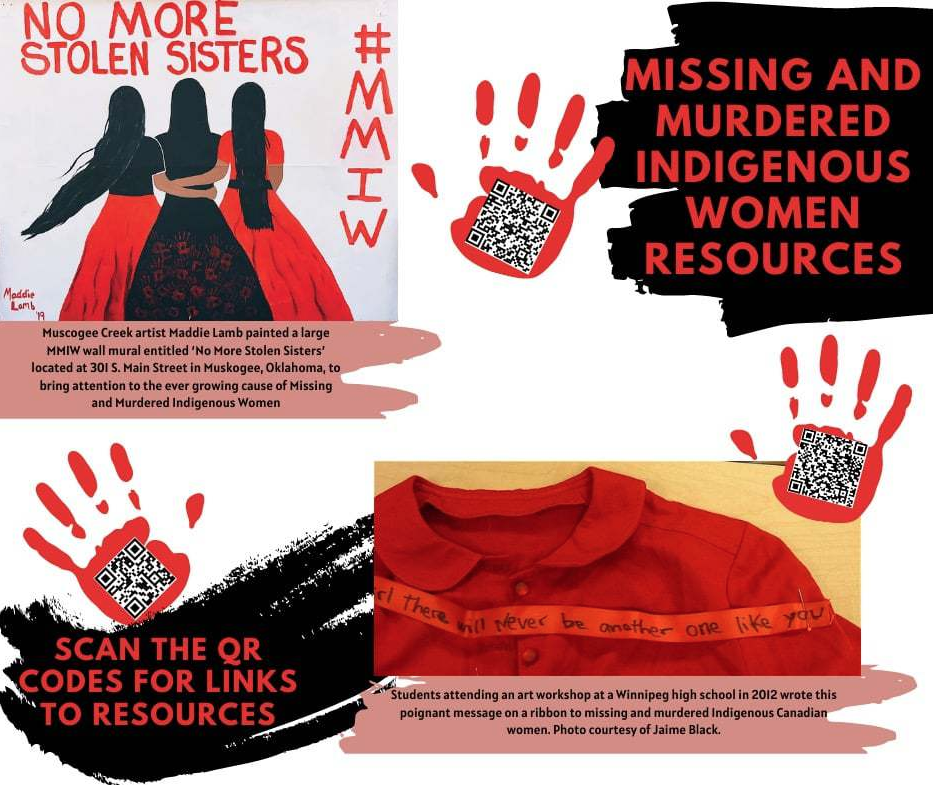

In most years, striking posters stapled onto bulletin boards and trails of red sand that symbolize lives “fallen through the cracks” are used to promote the event, Roberts added. Last year, students gathered around the Women’s Table, wreathed in candlelight and wearing masks painted with red handprints, to listen to speeches and a performance from the NACC’s resident drum group, Red Territory.

Despite the absence of such visible campus reminders, community members were still able to come together and create a sense of community through this year’s vigil.

“Within the community, there’s also been special consideration given to mental health; as I understand it, normally the vigil involves a very physical community presence/support,” said MeiLan Haberl ’24, who attended the vigil. “Since this isn’t possible this year, we have a buddy system to check in on other Native Yalies today — a literal support network, if you will.”

The message of the vigil, Haberl added, is clear: to “recognize what’s happening, stand together and look after one another,” particularly when existing institutions do not.

The Association for Native Americans at Yale was established in 1989.

Emily Tian | emily.tian@yale.edu