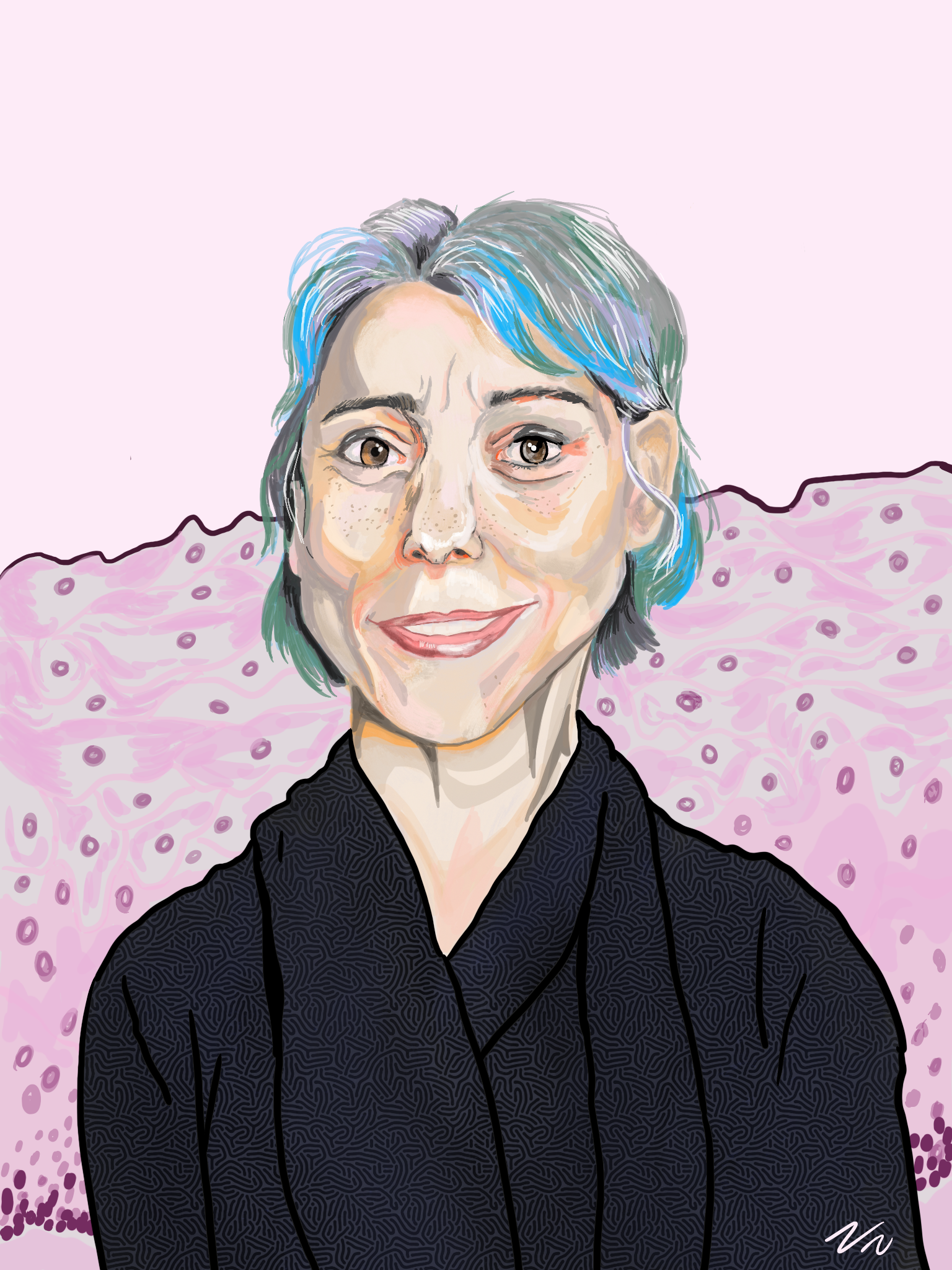

Valerie Navarrete, Staff Illustrator

Valentina Greco, professor of genetics at the Yale School of Medicine, has received the 2021 Momentum Award by the International Society for Stem Cell Research, or ISSCR.

This award is granted to scientists whose work made an impact on stem cell research and who show “a strong trajectory for future success,” according to the ISSCR website. Such describes the work of Greco, who has developed new tools that make it possible to observe stem cells in vivo and discover more than ever before about their structure and function. This work has been done simultaneously with her career-long commitment to being a mentor and training a new generation of scientists.

As both a woman and an Italian immigrant working in science, she has also continuously advocated for more equity in the field, which has most recently resulted in being named vice chair of diversity of the Genetics Department.

“Dr. Greco is redefining what it means to be a successful scientist,” Caroline Hendry, scientific director and advisor to the chair of the Genetics Department, wrote in an email to the News. “One of the most exciting aspects of [her] work is that she is always on the verge of a big discovery. Despite all her outstanding achievements and discoveries, it wouldn’t surprise me at all if her most profound work was still to come.”

Greco, who declined to comment for this story, conducted her early work as a postdoctoral fellow under the mentorship of Elaine Fuchs, the Rebecca C. Lancefield professor investigator at Rockefeller University. From there, she began carving out her own niche in the field, according to Christine Mummery, president of the ISSCR and professor of Developmental Biology at Leiden University.

One of her first steps was developing new tools with which to study stem cells. Previous scientists in the field had faced the challenge of not being able to observe the impact of their alterations of stem cells in real time, according to Antonio Giraldez, professor and chair of the Genetics Department and Greco’s husband. For example, if they wished to observe the effects of a small disruption on a single hair follicle, they would have had to take samples at various time points and then carefully observe those static images.

“When Valentina started her independent work at Yale, she … pioneered performing the live imaging of skin and hair, especially hair regeneration, with a multiphoton microscope,” In-Hyun Park, assistant professor of genetics, said. “She was able to kind of look at how stem cells divide and differentiate in lab imaging … which actually revolutionized the field. … She made many many findings based on those tools.”

One of her main findings using these tools has been that there exists a certain “plasticity” in the stem cell system, according to Giraldez. He explained that her research has revealed that while specific stem cells are important in biological processes, it is possible for other stem cells to take their place in the event of cell damage.

By visualizing the entire stem cell system, within a hair follicle for example, Greco has been able to show how the stem cells seem to function as a community. They work together and cooperate to solve problems, according to Giraldez and Mummery. Interestingly, they noted, this community has parallels to the lab environment that Greco has fostered.

“[Stem cells] act as a community, [they] tell their neighbors what to do,” Mummery said. “If one stem cell divides, its neighbor thinks ‘I think I’ll do that as well.’ … And I think that’s a sort of analogy to what she does in her lab. So it kind of fits very well with where she works. So, depending on what your neighbor does you say ‘Okay, that’s a good idea. Let’s do that.’”

Peggy Myung, assistant professor of Dermatology and Pathology and a former mentee of Greco, described Greco’s commitment to “close mentorship and attention.” As a young scientist, Myung was taught by Greco how to think about individual science explorations in the larger context of the field and what scientists are learning and discovering as a community.

While Myung began working in Greco’s lab when it was still quite new, very quickly Greco’s career began to take off. While Myung initially worried that this change would diminish the quality of mentorship experienced by Greco’s mentees, Greco’s commitment to these relationships has remained a steadfast feature of her career.

“In fact, I think her mission has become to have a larger role in shaping the opportunities for future young scientists,” Myung said. “Her passion is not only focused on pioneering new fronts in biology but to also pave the way for the next generation of scientists.”

Greco’s passion for helping other scientists has manifested itself in several ways. Beyond mentorship, she has also been a staunch advocate for diversity in the field of stem cell research. Mummery described how Greco has been “on the barricades” for women and people of all genders, speaking up repeatedly about the gender balance, or imbalance, in proposed programs put together by the ISSCR.

As an immigrant to the United States herself, she has also advocated for other international scientists in turn. Hendry shared that Greco has recently been appointed as the Vice Chair of Diversity in the Department of Genetics in order to continue this work conducted alongside her research.

“Her studies define the tip of the iceberg of what will surely be additional significant findings not only by members of the Greco laboratory, but by investigators all over the world,” Diane Krause, professor of Laboratory Medicine, Cell Biology and Pathology wrote in an email to the News.

The ISSCR was founded in 2002 and currently has over 4,000 members in 60 different countries.

Amre Proman | amre.proman@yale.edu