Amay Tewari, Photo Editor

On the heels of Yale’s most recent report about its financial health, students across the University are continuing to voice their demands that Yale reform its approach to spending.

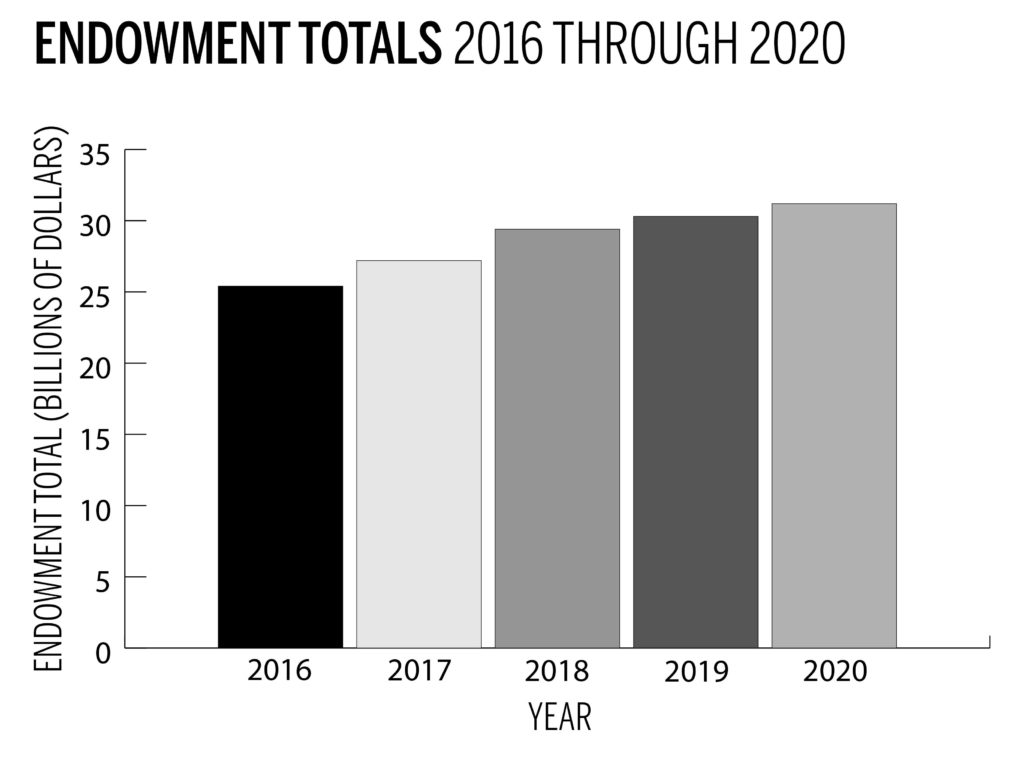

The University recently reported that for the most recent fiscal year, Yale’s endowment saw returns of 6.8 percent, and the University had a budget surplus of $125 million despite costs and lost revenue associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. In response, many students are calling upon the University to spend more money to support both the Yale community as well as the city of New Haven. The University expects to spend $1.5 billion of its endowment this fiscal year –– the most the University has ever spent from its endowment, according to the Investments Office’s annual press releases.

“Yale is lying a lot about their ability to spend money during COVID,” said Endowment Justice Coalition member Alex Cohen ’21. “They like to use scare tactics around the endowment and make it sound like the endowment is this very scary thing that you can’t understand and you can’t touch. … It justifies them implementing austerity measures that hurt people and are totally unnecessary.”

According to Cohen, the Yale Investments Office is taking its spending policy to an extreme, participating in what he called “endowment hoarding.” In Cohen’s opinion, the Investments Office is overly focused on accumulating wealth and generating high returns. In order to grow the endowment, Cohen said Yale invests in exploitative and extractive industries which shift money around the “worst places” in the economy.

Representatives from the Yale Investments Office declined a request for comment. University spokesperson Karen Peart declined to comment on Cohen’s allegation that Yale is hoarding wealth in its endowment and focusing more on generating high returns than on the well-being of the greater Yale community.

But according to Peart, because the endowment is a collection of gifts made to Yale over its lifetime, there are restrictions on how the earnings from the invested gifts can be spent with the requirement that they both support programs today and in perpetuity. In an April 21 message to the Yale community, University President Peter Salovey outlined how the endowment is used and the University’s plans to respond to the pandemic’s financial disruption.

“We are investing in the people of Yale,” Peart wrote in an email to the News. “The spending cuts are not contrary to our commitment to supporting our community. It is precisely that commitment that makes us act prudently since we are bracing for the uncertain months ahead of us.”

Peart added that Yale has provided and continues to provide “extraordinary” financial and other support to the Yale community during this difficult time, citing the partial lift of the hiring freeze, as well as a 1.5 percent increase in salaries of full-time faculty and managerial and professional staff earning less than $85,000 per year.

Cohen said that he feels the people who control the University’s wealth –– including Yale Corporation members, Investments Office employees and other administrators –– are more concerned with growing the endowment than servicing the Yale community.

“This makes the University more like a hedge fund with a school attached, instead of a school with an investments office attached,” Cohen said.

Another member of the Endowment Justice Coalition, Addee Kim ’22, called for Yale to invest more money in New Haven, saying that the University’s wealth hoarding is partly sustained by unjust tax exemptions on its properties. However, Kim added that the money owed to New Haven does not necessarily have to come out of the endowment.

Kim is part of the EJC’s reinvestment group, which they said extends the coalition’s divestment efforts and focuses on where Yale should direct the funds after divesting from “exploitative industries.”

“In our mind, a just investment is that in New Haven, given the history of segregated development in the city that Yale has directly contributed to through its wealth hoarding, its property expansion and its tax exemption,” Kim said.

But according to Peart, Yale has historically and will continue to spend substantial resources in New Haven. She said that due to Yale’s status as a nonprofit institution, the University is exempt from paying property taxes on its academic properties. However, Yale still remains New Haven’s third-highest taxpayer, paying $5 million in annual property taxes on its non-academic properties. She added that the University builds properties on existing land, so the city benefits through increased demand for construction, new opportunities for jobs and permitting fees of $5 million per year.

In the last fiscal year, Peart stated that the University paid $12 million in voluntary payments to the city of New Haven, which was the highest from a university to a host city anywhere in the country. Peart added that Yale spends over $700 million annually on New Haven and is the city’s largest employer.

“The only way to ensure that Yale will continue to be able to fulfill its core mission, while also continuing to support the New Haven community, is to maintain a prudent level of spending each year from our endowment, based on sound economic theory and analysis,” Peart wrote in an email to the News. “This is as much as we can responsibly spend without unfairly taking from those who will come after us.”

Alexander Kolokotronis GRD ’22 is one of the leaders of the Concerned and Organized Graduate Students at Yale. COGS is an organization of graduate students created last spring to push for a universal one-year extension on funding for all doctoral students. The group says that the pandemic disrupted their ability to complete their programs in the time they were originally stipulated to receive funding for.

Like Kim and Cohen, Kolokotronis believes that the University should prioritize investment in its students and in New Haven, citing the hundreds of millions of dollars in cash reserves as evidence that Yale has the resources to spend more money on the city and on the Yale community.

“We feel there is really no excuse for Yale to say that they can’t invest more in the community, they can’t invest more in graduate students, they should be even cutting into departments, such as the humanities,” said Kolokotronis. “It just doesn’t add up in either direction. It doesn’t add up when you look at the endowment, and it doesn’t add up when you look at the operating budget.”

Although separate organizations, Kolokotronis said that COGS and EJC support each other’s missions in terms of reforming how Yale chooses to prioritize endowment spending.

The Yale endowment is currently valued at $31.2 billion.

Julia Bialek | julia.bialek@yale.edu

Julia Brown | julia.k.brown@yale.edu