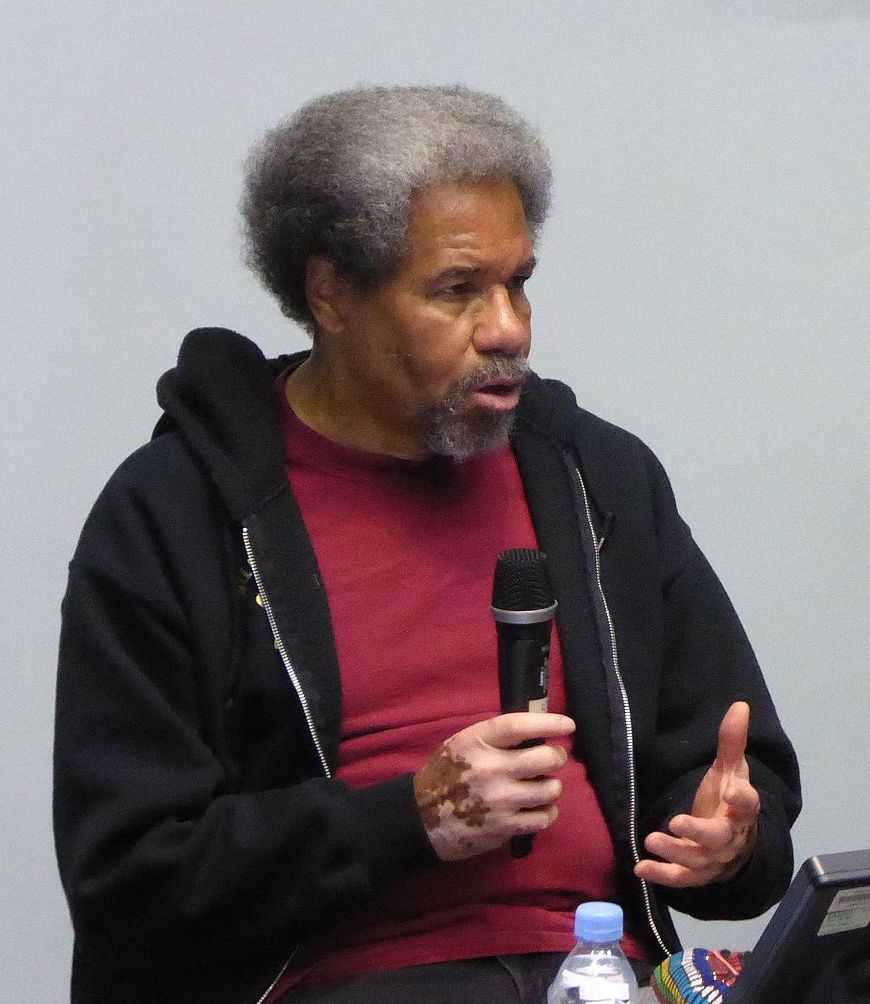

Wikimedia Commons

On Oct. 1, writer and activist Albert Woodfox — author of the Pulitzer-nominated memoir “Solitary” — spoke at Yale on his work and his experiences spending over 44 years in solitary confinement for a crime he did not commit.

One hundred and fifty students, faculty and alumni attended a conversation and Q&A with Woodfox over Zoom. The event was hosted by Irene Vázquez ’21 and co-sponsored by the English Department’s Initiative on Literature and Racial Justice — a series of readings and lectures that examine racial inequities — and the Yale Prison Education Initiative, which is an organization that provides resources and college courses to incarcerated students. In addition to being a larger event available to the Yale community, the conversation was part of the Francis Conversations with Writers Series.

At the conversation, Woodfox was accompanied by Leslie George, the first reporter to interview him after his release and with whom he wrote much of his memoir.

“I didn’t escape 44 years and 10 months of solitary confinement not being personally affected by it … but I’m not deterred … my will, my love for humanity is as strong as it’s ever been,” Woodfox said at the talk.

Professor Anne Fadiman, Yale’s Francis Writer in Residence, served on the five-person jury which recommended “Solitary” to the Pulitzer Foundation. According to Fadiman, “a student gets something different” from seeing an author in person and being able to interact with them.

As a young man, Woodfox was arrested frequently for petty crimes. In 1971, he participated in an armed robbery while on parole. Following this, he was arrested and sentenced to 50 years in the Louisiana State Penitentiary — also known as “Angola” — the nation’s largest maximum security prison.

Before he was transferred to Angola, Woodfox escaped from the courthouse where he was being held to Harlem, New York. It was there that he first encountered the Black Panther Party.

“The party gave me a sense of who I was and what I could achieve, and it gave me a direction, it gave me something to work towards, something to look forward to,” Woodfox said.

He was eventually found and sent back to Louisiana to be imprisoned.

In Angola, Woodfox organized hunger strikes, led a campaign to prevent prison sexual assaults, filed a lawsuit to limit strip searches and taught a fellow inmate how to read. He also formed a Black Panther chapter in Angola alongside inmate Herman Wallace. This advocacy made him unpopular among many prison inmates and authorities, and when prison guard Brent Miller was found murdered in April 1972, it was pinned on Woodfox and Wallace, despite physical evidence and eyewitness testimonies that suggested otherwise. Woodfox and Wallace were then both sentenced to solitary confinement.

Though Woodfox’s conviction was overturned four times, he was not released from solitary confinement until February 2016. Woodfox spent 44 years and 10 months in his 6-by-9-foot cell — the longest anyone in history has spent in solitary confinement — and he said he likely walked “100,000 miles” pacing back and forth in the small room.

Woodfox and Wallace, as well as activist Robert King — who was placed in solitary confinement on unfounded charges of a different crime — became known as the “Angola 3,” and their camaraderie persisted over their decades of imprisonment.

Vázquez told the News that she was “so nervous” to ask Woodfox questions, describing him as “such an easy person to talk to, but also one of the most impressive people” she had ever heard of. During the talk, Vázquez asked Woodfox questions that she, attendees and incarcerated students in the YPEI program had come up with. To her, involving incarcerated students in the conversation was the most important part of the event.

Ananya Kumar-Banerjee ’21 — who founded the YPEI’s Creative Writing Workshop and precipitated the collaboration between the YPEI and the English Department’s Initiative on Literature and Racial Justice — reached out to Fadiman to have the event transcribed and made accessible to YPEI students.

“It was certainly profound for me as an individual to hear about the liberatory power of writing for Woodfox,” Kumar-Banerjee told the News.

The transcription process was overseen by Gabrielle Colangelo ’22, YPEI Public Humanities Fellow and the leader of the YPEI transcription network. The group is responsible for making a transcription of the entire event available to incarcerated YPEI students.

The audience had positive reactions to the conversation.

“[Woodfox’s] sense of calm and equanimity … made me get in a really visceral way that he had some very remarkable personal qualities that enabled him to get through [the challenges he faced],” Fadiman told the News.

Benjamin Robb ’21 and Kyle Mazer ’22 agreed.

Robb told the News that, while he is privileged to be “protected” from Woodfox’s experiences, hearing him speak was “a moving experience,” noting that “you could see his integrity.”

Mazer agreed, adding that “everyone in the class was hanging on to every single word he had to say.”

Woodfox said that he and King have been traveling across the country since their release meeting with young leaders of the Black Lives Matter movement.

“I have four beautiful great-grandkids and I would hate to have them fighting the same battle 30 years from now that we are fighting now,” Woodfox said.

The Yale Prison Education Initiative was founded by Zelda Roland ’08 GRD ’16.

Simisola Fagbemi | simi.fagbemi@yale.edu