Dora Guo

I wake up each morning with COVID-19. A burn stretches out between my shoulder blades and knots in the soft flesh above my lungs. I inhale. The knot tugs tighter. I worry that I’m breathing corona-infused air. I worry that viral molecules somehow seeped through my closed window overnight. I worry that they’re now embedding in my nostrils. I exhale.

*

It was naptime in my progressive elementary school. My classmates were snoring. I couldn’t stop peeing. I asked to move my rest spot closer to the bathroom, which I tiptoed in and out of every few minutes, so as not to wake anyone. I was barely old enough to know the names of all my body parts, but I knew something was wrong with my bladder. My kindergarten teachers asked if it burned when I peed. If I sat on the toilet and thought of the feeling that beamed through my hands when I gripped the monkey bars too tight and that streaked down my ankles when I wore capris down the slide, then it did. I told them yes.

My mom picked me up early, and we drove to the pediatrician. The afternoon heat burned my skin — as if my body knew it was wrong to be outside my school walls with the weekday sun still hanging high in the sky.

“She has a UTI,” my mom announced to the nurse. Her voice was low, matter-of-fact. I nodded shakily. My head was limp, unhinged. The nurse asked me to pee in a cup. Her eyes were bulging like a frog’s, and one of them winked or maybe twitched as she handed it to me. “Should be easy.” And of course, since she said that, it wasn’t. She had jinxed it. I returned the cup mostly empty, except for a few drops pooling on the plastic bottom. “False alarm?” she asked, and this time I’m sure she really did wink. She still tested the little I provided her. We waited. I was declared “UTI-free.” It sounded to me more like a schoolyard taunt than a medical diagnosis. My mom talked to the nurse in hushed tones before saying it was time to leave. Her voice was not quite relieved enough, given that I was officially fine. I worried that maybe I wasn’t. She squeezed my hand a little too tightly and pulled me away from the pediatrician’s bowl of lollipops before I could stick one in my mouth.

*

I’m a hypochondriac. That’s probably what that nurse said to my mom 15 years ago. It’s what WebMD tells me now. Well officially, the site says I have “somatic symptom disorder” since apparently that’s the correct term for it. My symptoms match — and I’m relieved that, this time, they lead to an actual diagnosis. WebMD has also diagnosed me with fibromyalgia and acute necrotizing pancreatitis in the past two months. Their symptom checker has been a keystone of my Safari bookmarks Favorites Bar since I first discovered the site in middle school. This April, though, I’ve been afraid to check it. Afraid the slight sting in my throat and heaviness of my tongue and tight band around my stomach will all add up to the irreversible diagnosis of COVID-19. But then again, that’s why I use WebMD in the first place: to confirm my worst fears.

*

My first-grade teacher, Loren, wanted us to decorate the classroom with our fears. We were preparing for Back-to-School Night, that evening in September when parents come to our classroom and see what we’re going to learn. The idea was by the time they returned for Open House Night, that evening in May when parents come to our classroom and see what we actually did learn, our fears would be conquered. My friends wrote down “spiders” or “bats” or “rats” and decorated their pages with thin legs or black wings or beady eyes. I wrote down “coconut falling on my head.”

Loren called me over before dismissal. His eyes were blue and kind, with silver around the edges. They reminded me of my grandfather’s. He felt my fear was quite random. I explained that I’d gone to Fiji over summer break and learned that we’re ten times more likely to be killed by a falling coconut than a shark. And I’d already been afraid of sharks. I tugged at my hair, still braided and beaded from my time at the island resort, so he would believe me. I didn’t explain that the randomness was precisely what I feared — something terrible befalling me out of the literal blue.

*

My family’s thermometer is chewed from years of my overuse. The bite marks on the stem fit perfectly with the ridges of my teeth. Its metal tip feels cool against my tongue; it tastes a little like blood. My eyes roll in and down to watch the digital screen. 95.0. 96.2. Usually the numbers increase slowly, but today, they’re ramping up quickly. I can feel the stirrings of panic within me. I try to relax, to close my eyes, but with each beep they reopen to make out a new number. 98.3. 98.5. I pray for it to stop. I pray for silence. I pray it won’t hit 99. I take the thermometer out. I clean it. I put it back in my mouth. The bite marks. The metal. The beeping. The fear.

*

From the ages of 7 to 12, I had to brush my hair four times on each side. Two was too little a number. Three was the number of death. I don’t know how I first decided this, but it was a fact so ingrained in me, so viscerally believed by me, that surely, I couldn’t have just come up with it myself.

Sometimes, though, I would lose count when brushing. Sometimes, the bristles would be breaking through a knot in my hair, and I wouldn’t know how many strokes I had until four. Was it one more? Or two? I couldn’t remember. I’d always decide to do two more strokes. Just in case. If that meant I accidently did five on one side, that would be okay, as long as I evened it out on the other side. But, then, I would start to wonder: what if I’d already done four strokes when I decided to do two more? Then, I would now be at six. So now, I would die. Or, my mom would die. So, I’d grab my brush and do an extra stroke on the left and right side of my hair. Plus, maybe another. And then one more. Just in case. But what stroke number was that? I’d get so confused. This tingling would start in my scalp and rush down my body: the feeling of control leaving me. Strands of hair had been ripped from so much brushing. Fallen pieces were curled around my heels. The hair still attached to my head would be fluffy and feathery, puffing out at my ears . My head would hurt. But at least a coconut hadn’t landed on it, I’d think. Then I’d have to knock on wood.

When I knocked on wood, I could do it three times. I decided that made sense. For hair, three was death, but for wood, three was lucky. At night, before I fell asleep, I would reach my hand behind my head and bang my knuckles in the middle of my wood-paneled headboard so my family wouldn’t die. If my mom heard the clank of bone to wood reverberating through our quiet brick house, she would come check on me. I’d freeze mid-knock. I’d unclench my fist. My mom would smile. Her eyes would linger on the back of my hand still pressed against the wood, and the corners of her lips would curl downwards. She’d come lie with me in my twin bed, and I’d squish my body into hers so we both could fit. We’d stare at the glow-in-the-dark stars pasted on my ceiling. Their corners were turned upwards, having lost their stick after only a few years. She tells me now that I used to ask her, “Why are we here and where are we going?” She says, the first time I asked this, I’d barely been alive more than seven years, and yet, I already knew existential angst. I find this hard to believe, but she promises it’s true. We interlock pinkies and kiss our own thumbs as confirmation.

*

If I breathe four times without coughing then I don’t have the coronavirus. If I knock on the wood headboard above my childhood bed, then no one in my family will get it today. And if I take two puffs of the long-expired inhaler a doctor once gave me for a mysterious cough, that will ensure me two hours of good health.

*

When I was in high school, my aunt — healthy and young — died suddenly. A week after the funeral, I was lying awake at night and felt a fever start to build. First it was just a sour taste in my mouth. Then I felt liquid stewing in my ears, heating me from the inside. Goosebumps exploded on my body in patches — on the back of my neck, in the creases of my elbow, along the stretch marks on my inner thighs.

My family thought it was the flu. It lasted a week. Then two. A month. Then two. I couldn’t get rid of the fever. My doctor ordered tests — full panels to identify C-reactive protein levels and enzyme markers and blood cell counts. The Quest Diagnostics phlebotomist would laugh as I came in week after week. “Still searching?” he would ask, as he searched for a “fat vein” that wasn’t used up yet. He would fill a whole crate with tubes of red and sometimes yellow blood, and the next week I would return and somehow be able to still fill another. I was confused how I could give up this much blood. I worried I was losing too much. I wondered if this was causing the fever.

My mom, worn out from years of picking me up from school early and leaving doctors’ appointments late, wouldn’t lie with me during my feverish months. My dad, though, would sit on my bed and press wet washcloths to my forehead, assuring me over and over again that I would still wake up in the morning even if I fell asleep with my face burning.

When I was healthy in high school, my dad and I didn’t touch. I didn’t want a man’s hands (unless they were Harry’s in ninth grade or Will’s in eleventh) within a few feet of my widened hips or filled-out breasts. But, when I was sick, I wanted him to stroke away the hair that stuck to my sweaty face and hold my red palm in his until I fell asleep. And he did. Night after night. One time, when my fever was nearing 104, and I really thought that maybe I would die in my sleep — like my aunt, who didn’t even have a fever — I woke up to him still at my bedside in the morning.

*

Now, my dad won’t touch me. Even though, now, I would let him. I feel comfortable enough to talk about tampons in front of him. To walk around the house without a bra. To even let him kiss my cheek. But, now, he doesn’t want to. Now, I’m an unknown variable to him. I could have contracted corona when I opened the grocery store’s bag of baby carrots and ate one without washing my hands or when I accidentally touched the outside of my mask and then rubbed my eye. He seems to have contracted my hypochondria.

During dinner, if I use my own spoon to dole the hummus onto my plate, he’ll stop eating it. If I pass a plate to him, he’ll cover his hand in a napkin to receive it. I contaminate things for him. Nothing is ever clean enough for him. He leaves the table as soon as he has finished his dinner to start washing the dishes. And, after the dishes, he’ll scrub the counters. Then, the floors. Then the spaces I forget even exist in a house: the grout between bathroom floor tiles, the microwave turntable, the slits of the refrigerator vent.

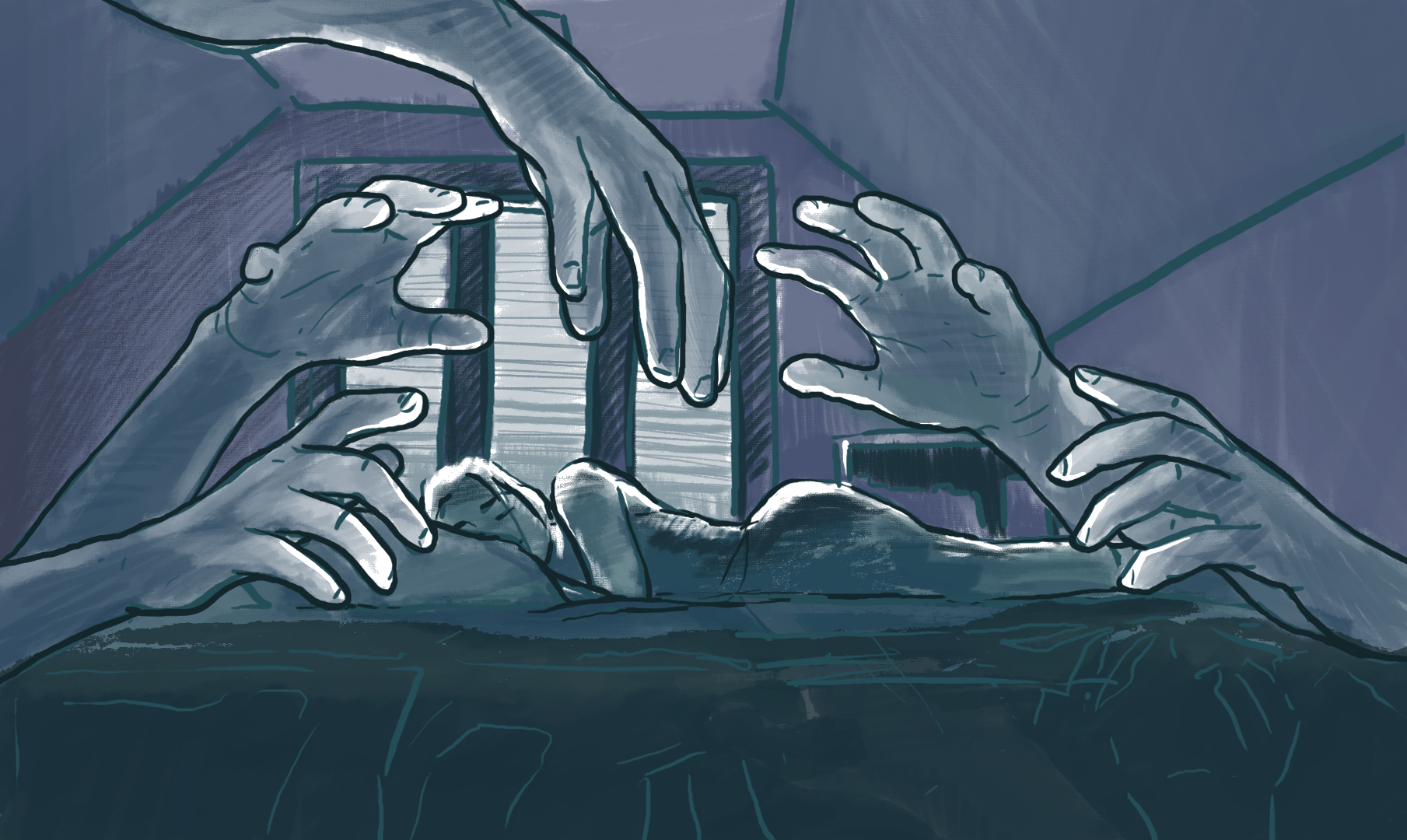

I drop a raw egg on the kitchen floor. I try to clean it up with soap and water, but he tells me it’s not enough. I try to salvage the spilled yolk with my hands, but he tells me it’s too late. He sprays the splattered mess with a garden hose from our patio. I watch him get on his hands and knees. I watch him use a sponge and bleach on a now spotless tile. I watch him scrub away all we can’t see — the invisible vapor of virus small enough that it escapes our eyes, big enough to kill.

*

At the end of high school, I had to use hand sanitizer if I touched a door handle outside my house and had to wash my hands if I touched someone with hair that looked greasy or skin that seemed oily. My palms were dry and smelled of alcohol no matter how much scented lotion I used on them. My mom took me to see a cognitive-behavioral therapist at UCLA. Dr. Williamson had blonde, shiny hair and an office littered with blocks and coloring books. She told me that germs disappeared from surfaces (including door handles and hair and skin) every two seconds. One one thousand. Two one thousand. And poof, she told me. The germs were gone. I told myself not to look this up in my AP Biology textbook. One one thousand. Two one thousand. I’d open the door to the public library. No hand sanitizer. One one thousand. Two one thousand. I’d use the water fountain after I saw someone with visible dandruff drink from it. No washing my hands.

*

My grandfather dies while we’re eating dinner. My parents are arguing about how long the coronavirus stays on the Styrofoam boxes of our takeout Thai food. Three days, they decide. I rub the containers with a Lysol wipe since I can’t count 259,200 seconds before touching them. My dad says he thinks I missed a few spots, though I don’t know how he can tell.

We get the call. My mom tells me later that the moment she heard her xylophone ringtone, she knew it was about her father. She answers. The nursing facility tells us he was having trouble breathing. I feel the burn between my shoulder blades. I feel the knot in my lungs. He had a fever. The sour taste in my mouth. The heating of my ears. The nurses had put him on morphine to relax him and open his lungs. I want my inhaler. Two puffs. He fell asleep. When they came back to check on him, he was dead. I crave my thermometer. I need to wash my hands. They say that it may have been corona, but they’re not going to waste a test. I want to knock on wood. Three times, paneled headboard. But I don’t move.

Friends send my family dinners for days. Delivery men who could carry the virus bring our food to us. We eat directly from the containers. I don’t bother to cover them in Lysol first. I don’t count to 259,200 before touching them.

I wake up in the morning to my mom crying into her phone — on a conference call with her siblings and her mom. My grandma, who didn’t need a nursing home, cries because she hasn’t seen her husband for weeks. She had missed him and now she has to miss him forever. This disease — their barrier, his possible silent killer. She curses it.

We try to have a moment of silence with my mom’s family over a Zoom call, but it’s interrupted by the crackling from my cousin’s shirt sleeve grazing his computer’s speaker. My mom tells us she can’t stop thinking about her father’s body, alone in the morgue, with no one to identity him, to say the Mourner’s Kaddish in his name, to speak a eulogy in his honor, to settle his soul before he disappears into ashes.

I lie with my mom, who’s curled like an infant on our living room chair that’s too small for both of our bodies. She asks me why he went and where he will go, and we cry. We leave our dinner to crust on our plates. My dad doesn’t clean. My dad doesn’t scrub. I don’t knock on wood. I don’t take my temperature. None of it was enough to save him. To save my family. To save myself. The twilight pushes through our living room windows. I open one to let it in.