Alex Taranto

On her first day back, Evelyn remembered why she had left. She had almost forgotten what Florida rain was like – to have the sky so heavy with clouds, the air so dense and suffocating, that the weight of the world seemed impossible to carry above ground. In her Uber down the long, straight expressway, she could barely make out the road in front of her, flickering in and out of view through the water on the windshield. When it rained, the grayness of St. Augustine was nothing like the grayness of New York, sleek and impersonal, heads down as crowds hurry to the nearest subway stairs. New York rain brought out a sense of confidence in Evelyn – unafraid and proud, just like a local. But in St. Augustine, the rain was lonely and desperate. Even when the clouds parted momentarily, all she could see was emptiness far around her, people hidden in their spread-out suburban homes, the flat landscape running until it was gone.

It was dark when she finally arrived at Lucky Li’s, a singular building on the side of the expressway. Pulling into the parking lot felt subconscious but familiar, like muscle memory. Ignoring the bright neon “CLOSED” sign in the window, Evelyn pushed open the door. Mrs. Li, a stout woman with short, practical hair, was standing in the doorway, hands on her hips. She evidently had been watching the window in anticipation of Evelyn’s arrival.

“Daughter, you’re all wet! Come in, come in, hurry! We were worried about you traveling in the rain. Why didn’t you call us on the way? Here, put your suitcase next to the door. Dry your shoes. We saved some food for you. You must be hungry! Did you eat? Your father is in the back tidying up, go greet him and then come back. Sit down, eat! Take off your coat. But don’t get water on the floor, we just mopped!”

Her mother’s Chinese was loving and impatient; it sounded different in person than it did over the phone. Evelyn dried her shoes on the mat by the door. When she was younger, she would have rolled her eyes, but instead she said, “It’s okay, Mama. I’m okay. Don’t worry,” and gave her mother a big hug. Even though her mother was shorter than her by almost a head, feeling her mother’s arms wrapped around her own slender body made Evelyn feel like a child again.

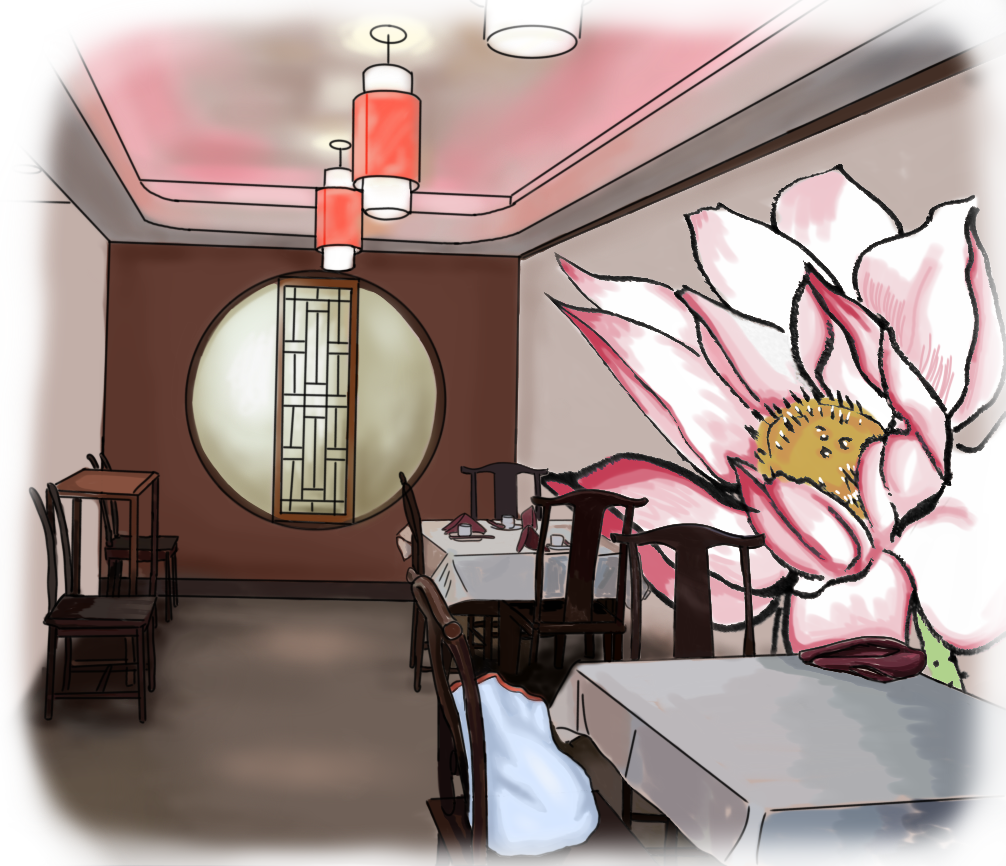

“We always miss you,” Mrs. Li said quietly, taking a deep breath. Still in her mother’s embrace, Evelyn looked around the room. She was painfully aware that nothing had changed – the painted walls, covered with lotus flowers, pink, white and green; the dried tea leaves in jars lining the cabinets, the Styrofoam takeout containers stacked in haphazard columns behind the counter, the cash register, old-fashioned, the yellow canopied patio with its three potted bamboo plants. Rain streaked the dark windows and the dining room smelled as it always did, of cooking oil and sesame. When Evelyn finally let go, she noticed tears in her mother’s eyes. She didn’t want to meet them, so instead she looked at the ground and tried to ignore the guilt churning in her stomach. “Eat up,” her mother said, before grabbing the mop and going into the kitchen.

Evelyn sat down at the table, where her mother had placed a bowl of rice, meat and vegetables – leftovers from the day. Next to it, a plate of cut fruit, arranged in the shape of a flower. Outside the rain continued to pour and an unexpected wave of nostalgia washed over her. It was those moments she remembered most, in the deep, dark quiet that rested over the dining room after closing, alone with twenty-eight empty tables and chairs.

—

On Evelyn’s third day back it stopped raining. It was half an hour after closing and Evelyn was helping her mother stack the dishes, one by one, in the dishwasher. When the restaurant had first opened twenty-seven years ago, Mrs. Li was adamant about not using a dishwasher, but quickly she learned that it was impossible to run a restaurant without one. They had spent the morning packing most of the clean dishes away into boxes. Already some of the restaurant’s fixtures were gone – Evelyn had helped Mr. Li upload a photo of the large fish tank in the dining area to Craigslist, and someone had already come to pick it up.

The small back window was open to serve as a vent and Evelyn could smell the wet grass outside. In New York, she never smelled grass, only gasoline, smoke and sewage. It kept her moving through the streets. Here, everything felt on permanent standstill. Go to school, work at the restaurant, eat, sleep, go to the beach. There was movement but no sense of time.

“Mama, you’ve already worked all day. Go take a break. I’ll do the rest.”Her mother laughed and her hands kept working.

“No, don’t be silly. I do this every day, what else am I going to do?”

“What are you going to do once you don’t have this anymore?”

They worked in silence, listening to the running water and the clanging of dishes.

“You don’t have to worry about that. But why don’t you pick up the phone when we call you? You’re always so busy. Too busy for your parents?”

—

Thirteen years ago, Mr. Li had asked Evelyn to paint the restaurant. It surprised her, because he was a simple man and Evelyn had never thought he had any interest in art. Some chefs found beauty and purpose in their food, but in truth Evelyn saw her parents more as cooks rather than chefs. The food they made was not even theirs, Chinese food catered to an American palate. The only time Evelyn saw them as chefs was on Chinese New Year: they closed the restaurant and made art in their kitchen at home, noodle soup and pork-and-chive dumplings and braised pork belly and a whole fish with head and tail, for good fortune. All the things that would never sell in white working-class Florida.

Alex Taranto

Evelyn herself loved art, as much as her parents loved to hang her art up on the walls of their home or the restaurant, no matter how much she protested. As a kid she drew for fun, but in high school she began to dedicate real time to painting, finding inspiration in imaginary landscapes or the internet. In Florida, public art was the neon-tubed logo of a bar in the city’s downtown, but in New York, when she had a rare break from work, she could drink her fill of its museums and galleries, and still there were countless more. She fell in love with the tactility of paint on a canvas, how it could be so moody, like Rembrandt, so expressive, like Van Gogh, so sublime, like Rothko, so feminine, like O’Keefe. Where else in the world could she see so many masterpieces with her own eyes?

But before she ever saw a Monet in person, Evelyn set up studio under the artificial lighting of the restaurant after Mr. Li locked up. She imagined a beautiful expanse of color, vibrant and clear. First, she painted the walls a light sky blue to represent water. When the base layer dried, she painted over it again, then began to stencil on images of pink lotus flowers, frogs leaping between them. She painted grass and koi fish swimming in the crystalline pond, reveling in the way her brush glided over the smooth wall. Occasionally, headlights from passing cars beamed through the dining room like flash projections, and the lotus flowers glowed bright and big like lanterns.

After three nights her parents came in to see the finished product. Mrs. Li was ecstatic and wouldn’t stop talking about how good it would be for business, alternating between praising Evelyn and scolding her for staying up so late. Mr. Li, on the other hand, just smiled and nodded.

—

On the fourth day, they closed early, when it was still light out. Mr. Li was out in the parking lot smoking. Business had been slow that day, but mostly it was because there was too much left to do. On their last call two weeks ago, Evelyn had told her mother to begin throwing things out, for example, the red and gold paper scrolls hanging along the counter and in the windows, the Chinese fortune décor that was now yellowed and faded. Her mother had agreed during the call, but clearly, she had either forgotten or changed her mind. Now, Evelyn teetered on the stepladder, delicately taking down each red lantern from the roof, while Mrs. Li held tightly onto the rungs.

Next was the large purple NYU pennant that hung on the wall near the kitchen. It had come in the mail with Evelyn’s admittance packet and she had given it to her parents. At first, they had been reluctant for her to go so far. “Why do you need to go to New York? What’s the difference?” they had said. Evelyn had sensed that they might have been hurt that she didn’t want to stay, so she focused her arguments around the financial aid she had gotten and the job opportunities in the city after graduation. On the day of her departure, her mother sobbed. Evelyn thought it was too dramatic, acting like she was never going to see her daughter again. She was excited for the bigger things that awaited her in New York, where she could dream further than she ever did in Lucky Li’s.

She carefully removed it from the wall, coughing at the dust cloud that came with it, and handed it to her mother.

—

The last day, when Evelyn came into the dining area with the mop and bucket after finishing packing up the kitchen, the room looked unrecognizable. Mr. and Mrs. Li were standing by the window. The tables and chairs were gone and the room was empty. The tiled floor was covered with plastic wrap and there was painters’ tape on the edges of the doors and windows. Beside them, there were three big buckets of white paint. They turned around to look at her; Mrs. Li looked apologetic. Evelyn had completely forgotten about the walls.

“Let me,” she said, taking a roller and tying up her hair into a ponytail. Compared to the humid air coming in through the open windows, the paint bucket felt cool when she dipped her roller into it. The painted frogs looked at Evelyn with their big eyes.

“Wait! Wait a minute,” Mrs. Li said. Paint was already dripping from the tip of the roller, forming a smooth pool on the dark floor, yellowed by the overhead lighting. “I need to take a picture.” She pulled out her phone quickly and snapped some photos, the camera shutter sound audible in the quiet. Then she put her phone away in her back pocket. “OK, Evelyn. You can paint now.”

Three hours later, Mr. Li had gone outside to smoke again. Mrs. Li let go of the stepladder and Evelyn came down. Somehow, with the empty walls, the dining room felt smaller and foreign. It was as if all of her memories of her childhood were erased, buried deeper and deeper under each layer of white paint. All it was now was a singular building on the side of the expressway, with no trace of her parents’ twenty-six years of toil.

—

And so, besides the regulars, the news went quite unheard. A soft shuttering, quiet in the middle of the night, when the roaring of the cars on the highway dimmed, when the floors were all scrubbed and the wall paint dried white. Mr. Li switched off the neon sign for the last time. In the dark window, it was almost invisible.

Evelyn helped her mother load the minivan with the remaining items. Inside, the building was now white and clean, empty of everything that was theirs, ready to house something new. It seemed as though overnight Lucky Li’s had disappeared.

The next day on the plane, Evelyn watched the flat, unmoving expanse of Florida out the small window. The plane began to taxi; New York was waiting for her. During the captain’s announcement her phone buzzed once, then again, then again; the passenger next to her, an elderly lady with red lipstick, gave Evelyn a disapproving look. She moved to put her phone on airplane mode and glanced at the messages.

Hi

Are u on plane?

Call us when u are on plane.

We miss u. Love always.

[photo]

The photo was of the walls. Blue, green, pink, and white – those were colors she had dreamed up, nowhere to be found in the swamps of her hometown. Frogs leaping between the lianhua, the lotus flowers; koi fish that had found a home in the ponds, shaded by the lotus’ large, fan-like leaves. The windows were open and outside it was dark. In the middle of the empty room were Evelyn and her father, each with a roller in hand, white paint pooling on the floor, and of course, her mother’s thumb in the corner, the lightest filter of flesh that tinged each of her memories, now and forever.