MEN’S BASKETBALL: For James Jones and Yale, scheduling a real struggle

“Yale is like playing a high-major team without the high-major cache,” Sacred Heart head coach Anthony Latina said. The Bulldogs haven’t managed to schedule an in-state opponent since the 2016–17 season.

muscosportsphotos.com (in-line by McCormack)

Back in December 2014, Yale men’s basketball made headlines after upsetting defending national champion Connecticut, 45–44. With just 3.5 seconds to play on that first Friday in December, UConn led by two and guard Javier Duren ’15 inbounded the ball under the Huskies’ basket. Then-junior Jack Montague streaked to the corner, received a long pass from Duren and swished a game-clinching three-pointer.

The Yale bench went wild. 9,500 others in Storrs, Connecticut, were not as thrilled.

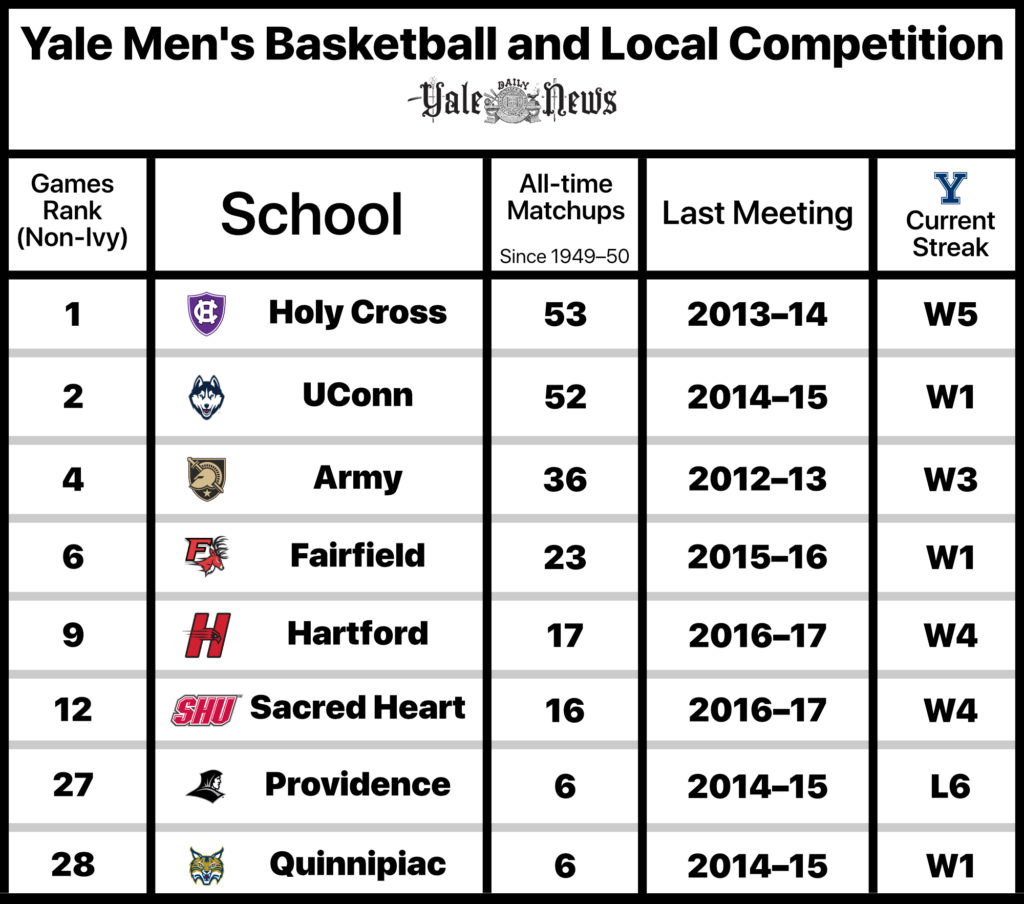

UConn — which has played 52 games against the Elis since the start of the 1949–50 season, ranking the Huskies second on Yale’s list of most frequent nonconference opponents — had not lost to Yale since 1986. But now, five years have passed, and the two teams have not met each other since.

Under head coach James Jones, Yale has become a perennial Ivy League contender and one of the strongest, if not most underappreciated, NCAA Division I men’s basketball programs in New England. Since the start of the 2014–15 season, the Elis are 117–55 overall and 56–19 in the Ancient Eight. But the consistent success has turned scheduling into a nightmare for Jones, as formerly annual opponents have disappeared from the nonconference slate. Although in-state opponents once composed many of the program’s most familiar nonconference competition, the Bulldogs have not faced another Connecticut team since the 2016–17 season, the year after Yale’s first trip to the NCAA Tournament under Jones.

“We’ve struggled over the last several years of being able to find teams in the region that would actually play us,” Jones, who is in his 21st season as head coach, said. “We don’t really have a lot of teams in the region we can actually get games with. We haven’t had a team on our schedule in the state of Connecticut in three years. Teams have dropped us, and they don’t want to play us.”

As of last week, Yale again does not have any opponents from Connecticut on its 2020–21 schedule, Jones told the News. He said Yale and Quinnipiac, led by third-year head coach Baker Dunleavy, originally intended to play a game at some point during the 2020–21 season, but the two teams could not find a suitable date.

In order to play at its John J. Lee Amphitheater in New Haven, Yale resorted to scheduling games against two Division III teams this season: Oberlin, which visited in early November, and Johnson and Wales, which came in mid January for the Elis’ fourth and final nonconference game at home.

“It’s very difficult to get people to come here and play at Yale, and the reason why we have these [DIII] games on our schedule is so we can actually play at home,” Jones said after the Elis defeated Oberlin, 94–37. “It’s a problem with scheduling. It’s the hardest thing you do in this business besides recruiting, and it’s as important as recruiting is.”

A decade ago, playing a Power Five opponent on its own court every few years was not out of the ordinary for Yale. The Elis would schedule a two-and-one, travelling to an opponent for two away games and playing one home contest against them over a stretch of three or four years. Florida came to JLA in 2013, Stanford visited in 2008 and Wake Forest travelled to New Haven in 2003. Now, no teams are willing to do that, Jones said last fall.

Smaller programs in Connecticut and neighboring states have followed a similar trend over the last few years. The Bulldogs have faced Holy Cross more times — 53 — than any other nonconference competition since the 1949–50 season, but have not played them since 2014. For Army, which ranks fourth on the list with 36 matchups, the moratorium began after 2012.

Fairfield has played 23 games against Yale since the 1949–50 season, the sixth most among all nonconference opponents, but has not faced the Elis since 2015. After facing the Bulldogs in 16 consecutive years, playing its program’s first-ever game against Yale during Jones’ third season in 2001, Sacred Heart has not met Yale since the 2016–17 season. Yale’s streak of 13 straight seasons against Hartford similarly ended after the same campaign.

“We’ve been a young, rebuilding team, they’ve been a very veteran team, and it just wasn’t the right fit for us at this point,” Sacred Heart head coach Anthony Latina said. “If there’s ever a situation where a program is rebuilding and Yale or anyone included has a core group of guys, it might not be the right fit for your young guys to go in and get beat up by an older, veteran team. Scheduling is extremely important for a variety of reasons: from a competitive standpoint, from a recruiting standpoint, from a profile of your program standpoint.”

Latina said Yale’s difficulty scheduling with local teams is mostly a testament to the consistency Jones has developed in New Haven. Men’s basketball contacts at Fairfield, Hartford, Quinnipiac and UConn did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Alongside recruiting, scheduling is one of the most important job responsibilities for a DI men’s basketball coach, Latina said, agreeing with Jones. Actually coaching, he said, is a “distant third.” Crafting a nonconference schedule forces coaches to balance logistical concerns — whether enough rest exists between games, for example, or how long and costly travel will be — with the seemingly incompatible goal of combining a high strength of schedule — playing talented, respected opponents — with the best possible record.

Latina emphasized scheduling as a “tricky, tricky” process. He also considers each opponent’s style of play. Gaining exposure to a variety of tendencies and tactics is important, but playing against teams that mimic conference opponents is also helpful. A mid-major that expects a conference opponent to play a 2–3 zone, for example, might try to schedule a nonconference game against Syracuse, infamous for its zone, in preparation.

This season’s Yale group has never faced local programs like Fairfield, Providence, Quinnipiac and UConn in their careers. Only the seniors have played Sacred Heart and Hartford. Instead, this current collection of Elis have grown accustomed to longer road trips against a different set of annual opponents, teams like Albany, Lehigh and Vermont. The Bulldogs and Catamounts have met in 13 consecutive seasons.

“We got a couple teams we can play home and away every year,” captain and guard Eric Monroe ’20 said. “[They’re] not real rivalries, but [we’re] kind of familiar with each other, so those are always fun tests.”

For Jones, however, a weeknight trip to Albany is not ideal. Yale made the trip this past December. Playing against instate opponents, he said, would get players back to campus by 10 p.m. and not require them to miss any classes.

Money is another concern. Power Five programs and even some other mid-major teams of higher stature often offer guarantee or buy games to smaller opponents — the home team’s athletic department will pay the visitors a sum to play the game, typically around $80,000 or $90,000 according to one report last year, no matter the result. Paying another program to visit guarantees a home game and often a win against a smaller, less successful team, while the smaller program earns money for its athletic department and operating costs, while offering players a chance to participate in the spectacle of high-end college athletics at schools like Duke or Kentucky.

Latina said the exact group of teams that offer buy games is always evolving, especially among strong mid-majors. Five or 10 years ago, schools in the Atlantic 10 and Colonial Athletic Association never bought games, the coach said. Now, many of the better teams in those leagues pay opponents in order to secure home games, and Latina said he would not be surprised if top talent in the Ivy League might start doing the same. Although Jones said Brown and Columbia have bought a few games before, Yale has not.

“Where is that money coming from?” Jones said. “I mean, there’s no more money like that in our budget to be able to do that … Even if we were buying games, it still would be hard. It wouldn’t be like they [say], ‘Oh yeah, let’s go play ’em.’ It still would be very difficult. And it’s ridiculous because years ago if we take a look at the schedule, you see Quinnipiac down here, you see Central Connecticut down here, you see Holy Cross down here, you see Army down here. None of those teams will play us.”

Sacred Heart faced Providence and UConn to start the season, two larger programs with a lot more historical success than Yale. Those schools pay money, Latina said.

But the Pioneers also traveled to UConn and Providence without the burden of expectation. Although Yale — which stands at 46th in the 2020 Pomeroy College Basketball Rankings, or KenPom, as of Wednesday night — ranks almost 30 spots ahead of Providence at 70th and UConn at 76th, the perception of dropping a game at Yale is much different than the optics of falling to a historical Big East powerhouse.

“Yale is like playing a high-major team without the high-major cache,” Latina said. “If you go into UConn and play great hoops, that’s seen as a feather in our cap, you know what I mean? You play Yale and lose, you lose … It’s like playing a team that’s at the level of some of these higher profile programs without the financial incentive or the cache if you do play well and win. People [who] really know basketball know that’s a great win, but your average fan probably doesn’t.”

Jones said he is frustrated — difficulty scheduling makes what is already a complicated, strategic process even more challenging.

But the problem is one he has created for himself, a symptom of Yale’s success.

“I can feel for James and what he’s going through,” Latina said. “And I hope that we have that problem at Sacred Heart in the next year or two.”

William McCormack | william.mccormack@yale.edu