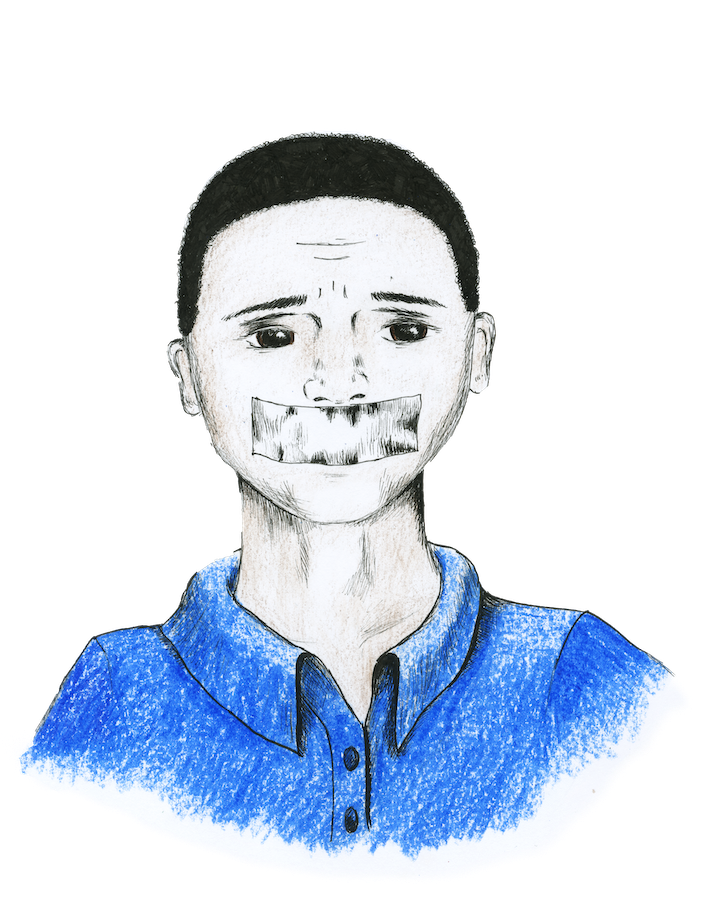

When We Take Offense

Harvey Mansfield, the free speech debate and how political correctness plays out in the humanities

Claire Mutchnik

When the Directed Studies program first announced that conservative political philosopher Harvey Mansfield would deliver the first mandatory colloquium of the year, students reacted in outrage.

Talks of putting up protest signs and boycotting the event flooded a group chat of around 50 Directed Studies students, who saw Mansfield’s previous statements on gender roles, affirmative action and homosexuality as offensive.

“As soon as I started looking into him as an academic, his academic and personal record, I definitely wanted to object to him coming to speak at Yale,” Directed Studies student Cameron Chacon ’23 said.

Days leading up to Mansfield’s talk on Oct. 7, students and faculty members debated whether a lecture from the controversial speaker deserved to be promoted and even entertained. While students saw inviting Mansfield to the year’s first colloquium as an act of conferring undue honor, professors extolled his academic accomplishments and emphasized that students must be open to unorthodox views they disagree with. Humanities students should be eager to be surprised and willing to change their mind, English professor Mark Oppenheimer ’96 GRD ’03 said.

“I don’t think that today’s campus culture on the part of the students or the faculty really revels in the journey as much,” Oppenheimer added.

When the chalk dust had settled, however, Mansfield’s talk went off undisturbed in Room 101 of Linsly-Chittenden Hall. Students listened as Mansfield — a respected scholar with controversial views — spoke about science and the humanities. The loudest disruption was seats creaking as a few shifted in discomfort when Mansfield asserted that only Western civilization had the capacity for self-criticism. Academic expression won out over political correctness in the case of Mansfield’s colloquium.

The controversy surrounding Mansfield’s colloquium comes amid heated discussions about the extent to which students should engage with contentious, even hurtful, ideas. In the four years since a Yale professor resigned over furor surrounding her email that students should be free to don any Halloween costume — even a potentially offensive one — Yale seems to have learned something about managing strong differences of opinion.

But students’ initial reaction still shows a pervasive hostility to views that some regard as scary or hurtful. Afraid of offending students, some humanities professors said they have altered their syllabi to bypass controversial works. They’ve seen students self-censoring in fear of ridicule from their peers. Particularly in the humanities, a discipline built on nuance and interpretation, professors said that when controversial opinions are stifled, universities lose out.

____

Mansfield is a complicated figure. A respected scholar, he serves as Harvard’s William R. Kenan, Jr., Professor of Government. He has authored 15 books on topics including manliness and co-translated Machiavelli’s book Discourses on Livy. His works won him acclaim — including the National Humanities Medal from the President in 2004 — and condemnation from critics. Mansfield’s 2006 treatise entitled “Manliness,” in which he argued the attribute had been lost in today’s gender-neutral society, prompted criticisms of misogyny from philosopher Martha Nussbaum.

In the past, Mansfield has argued that affirmative action encourages pervasive grade inflation at universities. In 1993, he testified in favor of Colorado’s Amendment 2, which stated that gay people should not be protected as a marginalized group. He also argued that the feminist idea of sexual independence was incompatible with feminine modesty in a 2014 piece for the Washington Examiner.

In an interview, Bryan Garsten, who is the chair of the humanities program, said he invited Mansfield to speak at Yale after taking an interest in his 2007 Jefferson Lecture on what the humanities can teach science. But several Directed Studies students said they took issue with his arguments on manliness, as well as his stance against affirmative action and his comments that being gay is “shameful.”

First-year Directed Studies student Madison Hahamy summed up in an op-ed published on Oct. 7 her qualms with the program inviting Mansfield to speak. Her article claimed Mansfield was racist, sexist and homophobic.

“Those outwardly dehumanizing views, there is no value in engaging with them,” Hahamy said in an interview with the News.

In an op-ed of his own, Garsten responded to Hahamy and argued that premature accusations with little evidence were on the rise in the current public discourse. Those accusations lead people to avoid or condemn ideas without understanding them, Garsten said.

He also met with members of the Directed Studies Student Advisory Committee, which included both supporters and opponents of the invitation. Garsten fended off student pressure to disinvite Mansfield or make attending the colloquium optional. Following the meeting, he emailed all Directed Studies students reaffirming his decision to retain Mansfield to speak and creating forums for students to question the Harvard professor directly.

___

Almost exactly four years before Mansfield delivered his colloquium speech, a controversial email from then-Silliman associate master Erika Christakis unleashed a series of heated conversations about free speech and race at Yale.

In December 2015, Christakis resigned after retaliation for her email, which argued that her students in Silliman College should choose their own Halloween costume, even at the risk of offending others.

In the wake of the email, a group of students confronted Christakis’ husband and then-Silliman Master Nicholas Christakis and demanded he apologize for the views that had violated their campus safe space.

In the midst of the tumult, Yale became the center of national discussions about the limits of free speech and universities’ obligations to foster a safe and welcoming environment for all its members. At the time, University President Peter Salovey said that he felt “deeply troubled” after meeting with students of color who reported feeling “in great distress” at Yale.

The letter that student activists penned at the time contains similar language in Hahamy’s October op-ed. “We, however, simply ask that our existences not be invalidated on campus,” the letter stated.

Similarly, in accusing Mansfield of being racist and sexist, Hahamy said, “It is emotionally draining to have to engage with him. I should not have to prove my worth as a human just because Harvey Mansfield believes I am less intelligent than my male peers.”

_____

In an interview with the News, English professor David Bromwich attributed regulated speech to an emerging notion that words can be toxic. Bromwich said that some students believe that “words can cut so deep they can injure,” that speech can be so vitriolic it can physically traumatize someone.

Oppenheimer also noticed a stark difference between students’ perspective of their own resilience among his peers at Yale in the late 1990s and the students he teaches today. When Oppenheimer attended Yale, he observed students pretending to be tougher than they were. By contrast, today’s students feign fragility and emphasize self-care.

These beliefs, professors said, are particularly unproductive for the study of humanities, which often require students to engage with ideas they disagree with.

“The danger of these too hasty judgments is that they lead us to miss out on what we can learn from the very imperfect creatures who came before us,” Garsten said in an interview with the News. He pointed to Aristotle’s Politics’ defense of natural slavery as an example of a disturbing element in a substantive work.

Mansfield himself asserted that an individual could not be a scholar of the humanities unless they were receptive to opposing and potentially politically incorrect ideas.

“The humanities are in the realm of opinion as opposed to the more stricter standards of fact that are possible in the sciences,” Mansfield said in an interview with the News. “One of the features of the humanities is that facts need to be interpreted and interpretations will differ.”

In his experience, many of the current humanities scholars don’t understand this facet of their studies. Addressing Directed Studies, however, defied this conception. Mansfield described feeling “quite at home” delivering the colloquium.

___

In an interview, Bromwich said he deemed it encouraging that students then decided not to disturb Mansfield’s talk. The colloquium came and went without a single student protest.

Still, some students in the Directed Studies program said they left the colloquium feeling dissatisfied. Chacon ’23 said he felt the colloquium “detracted” from free speech because Mansfield peppered his talk with controversial and unnecessary buzzwords and did not adequately respond to student questions.

Chacon asked Mansfield to evidence his assertion that Western civilization had a unique propensity towards self-critique. Mansfield replied that his judgement should be based on his “vast knowledge of non-western civilizations.” But since he lacks such knowledge, students should take his statement as a proposal to be investigated rather than as a fact, Mansfield added.

Chacon said Mansfield espoused some “Western supremacist views or even white supremacist views, … or at the very least exclusionary views,” and that the colloquium’s format—with Mansfield behind a lectern calling on students with raised hands— shielded the professor from accountability for his comments.

But for his part, Garsten said the colloquium could serve as a model for discourse between opposing opinions. He was “really happy with how the Directed Studies students seemed up for that.”

Though Hahamy conceded there were valid reasons to invite Mansfield to speak at Yale, she also questioned why the talk was mandatory. Hahamy considered it a pointed message to select Mansfield to deliver the first colloquium.

“He made these comments that are disparaging people in this program,” she said. “He’s already actively not working to reflect this program.”

She urged empathy for people who didn’t want to assume the “emotional burden” of engaging Mansfield in conversation.

___

The initial uproar following the announcement of Mansfield’s lecture reflects students reluctance to engage with views they deem to be offensive.

In an interview, Hahamy observed that despite forums for students to challenge Mansfield, the colloquium may have only seemed to be a free exchange of ideas if viewed from the outside, as students could not alter Mansfield’s entrenched ideologies. “Me being an 18-year-old raising my hand is not going to change his mind because he’s had those questions before,” she said.

But in a Wall Street Journal opinions piece, Mansfield argued that many of today’s college students had a novel, unproductive definition of speech as a means of changing someone’s opinion. Words had changed their meaning; students saw them as an expression of power to manipulate, cajole, and spar with opponents. He said in an interview with the News that free speech was “possible but not in vogue.” Instead, the concept of speech had been perverted as analogous to argument.

A 2017 Gallup and Knight Foundation poll laid bare a discrepancy between policy and practice in the response to invited speakers at universities. A survey of about 3000 U.S. college students yielded more than a third — 37 percent — of respondents deeming it sometimes acceptable to shout a speaker down, with one in 10 sometimes approving of violent disruption. At U.S. institutions of higher education, the impetus for students to avoid views different from their own lingers.

Oppenheimer said Yale should try to empower students to believe they can encounter most of adulthood’s challenges with “self-possession and confidence and almost invincibility.” He added, “If students feel physically violated by encountering a Republican, then we have not made you capable, resilient people.”

Professors also noted that their intent to educate sometimes loses out to following the path of least resistance. Bromwich held that when crafting syllabi, some professors succumb to the easy default of avoiding controversial works or passages altogether to avoid extreme reactions from students.

Oppenheimer affirmed that academics owe it to authors to encounter their works as they are, even engaging with potentially disturbing ideas. Professors “have chosen a career that values the life of the mind and that also values truth more than comfort,” Oppenheimer said.

Professors who raise unorthodox ideas may find themselves up against students who react forcefully to such discussion. “I’m afraid of my students in that regard,” Oppenheimer said. “I think most professors are afraid of our students now.”

Even Mansfield, a tenured and toughened professor, isn’t exempt from pressure for political correctness. Though he still teaches much of the Western canon, as he has since his start at Harvard, he has had to be more cognizant of how students receive the material. “I begin to step my way more cautiously,” Mansfield said. “When it comes to certain passages one has to be careful not to arouse the ire of the politically correct.”

Mansfield also observed students self-censoring in fear of offending their peers. Students police each other in classes, retaliating against or ostracizing their peers who have controversial views. Mansfield evidenced his point with the same topic that has garnered him such fraught controversy: the relationship between men and women. He referred specifically to Socrates’ arguments for equality between the two sexes in Plato’s Republic. He has observed his students afraid to raise unorthodox questions and opinions on the argument for fear of damaging their reputations.

A News survey administered to Yale College students showed this extreme caution holds sway at Yale, particularly among conservative students. Of the responding sophomores, juniors and seniors, 75 percent of conservative students reported feeling “uncomfortable” or “very uncomfortable” divulging their political views on campus, while only 8 percent of liberal-identifying students felt the same.

“My students tell me that the chief constraint they feel on freedom of expression these days is that of social shunning by fellow students, who might not respond well to politically ‘incorrect’ points of view,” Robert A. Lovett Professor of Military & Naval History John Gaddis said.

Per Mansfield, one of the reasons for attending a liberal arts university is to encounter a diverse array of intelligent opinions and debate amongst peers. “When that kind of argument becomes dangerous to your reputation, you fall silent, and you miss a lot,” Mansfield said.

Oppenheimer asserted that students would not have fully mined the opportunities of a liberal arts education if they had come to and graduated from college with unchanged perspectives. “If you knew everything when you were 18, what are you paying us for? A job at J.P. Morgan?” he questioned.

__

Despite concerns about the state of free speech at institutions of higher education, Keith Whittington, the William Nelson Cromwell Professor of Politics at Princeton University and author of “Speak Freely: Why Universities Must Defend Free Speech” said he sees cause for tentative optimism.

Whittington noted a shift in the last two or three years that suggested Yale and its peer institutions were becoming more tolerant of expression. He attributed this change in part to incidents like Yale’s Halloween controversy which frightened people that universities were on a trajectory towards totalitarian restriction of speech. Some institutions responded by consciously emphasizing their values and policies to welcome free speech on campus.

Still, he said, it’s especially challenging for universities to combat this chilled speech. It requires a cultural shift, not merely a policy change. He predicted a persisting challenge for liberal-leaning universities to push back against a tendency towards truncated conversations.

Along with the worry of stifled speech, Oppenheimer held that joy was a significant, though oft-overlooked, casualty of campus resistance to difficult ideas. Students missed out on true openness and liberation among peers.

“When people are fearful that their friends will go on social media and destroy them for saying what they believe, we lose freedom, good intellectual discussion, and joy,” Oppenheimer said. “So much of the discourse is the fearful discourse of what do we want to avoid. But, what do we want to embrace? Freedom.”

Rose Horowitch | rose.horowitch@yale.edu

Correction, Nov.16: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that Mansfield wrote a book on Roman historian Livy. In fact, Mansfield co-translated Machiavelli’s book Discourses on Livy.

A previous version of the article also incorrectly stated that Garsten met with three DS students representing the protestors. Instead, Garsten met with members of the DS Student Advisory Committee, which he said seemed to include both supporters and opponents of the invitation. Instead of three, there were around ten to fifteen students in that meeting,

The article also previously stated that in response to Chacon’s question at the Colloquium, Mansfield said his judgement about the uniquely self-critical character of the Western canon was based “vast knowledge of non-western civilizations.” This is incorrect. Chacon said his judgement should be based on such knowledge, but since he didn’t have that, students should take his statement as a proposal to be investigated rather than as a fact.

The article has been updated to accurately reflect Mansfield’s academic work and the circumstances leading up to and at the Colloquium. The News regrets these inaccuracies.