After three days of bathing in the Myrtle Beach sun, sipping on sangria from red cups and jumping waves, I fell sick. So I sat in my Chapel Street apartment for a day, on a diet of Tylenol and water, binge-watching the Netflix drama The OA. The OA is about many things — a blind girl who regains her sight, a telepathic octopus Old Knight, a video game that brings its players to a mysterious house — but at heart it is about the multiverse.

In the multiverse, parallel universes exist side-by-side. In one, Sonia and I were not in the same Froco group — we never met and never became best friends. Clinton was president, not Trump. I took Organic Chemistry instead of Directed Studies. I never fell in love with philosophy. In another, I never even came to Yale. In one, I was born a boy.

There is no way for me to access these universes, only imagine them. I gain comfort in the other me’s living other lives but ache for the universes I will never live.

But what if multiverse exists, in this universe?

Think of the universes we inhabited. That third floor lecture hall in LC where we learned about the growing block theory of time as snow pelted outside the window. The Hopper Cabaret, where we spent our nights rehearsing for our spoken word show, the world outside the theatre disappearing as we listened to each other. The attic of the Yale Daily News building, where we gave each other lap dances to Glen Campbell at 1am as we proofread the Friday morning spread. That house on Lynwood, where we played kiss marry kill and showed each other parts of ourselves that were difficult to share. Our favorite table in Hopper, where we had lunch together every other day before your astronomy lecture. The apartment where the three of us talked about empathy, lab rats, and our freshman year mistakes, as Rihanna belted from the speakers.

As I read books, wrote essays, heard from brilliant minds and met new people, I started to question the basic tenets of the universe I had always known. Taking a class on citizenship made me wonder what allowed me to belong to a country any more than someone without a passport who had fled here out of fear of persecution. Reading Althusser prompted me to consider how everything personal is political, from who I desire to what I value to how I like my coffee in the morning. Attending my first protest made me wonder how our emotions — anger, blame, contempt — could be channeled productively. Taking a class on human evolution led me to revel in how all that we take for granted — fire, tools, language — had to be discovered.

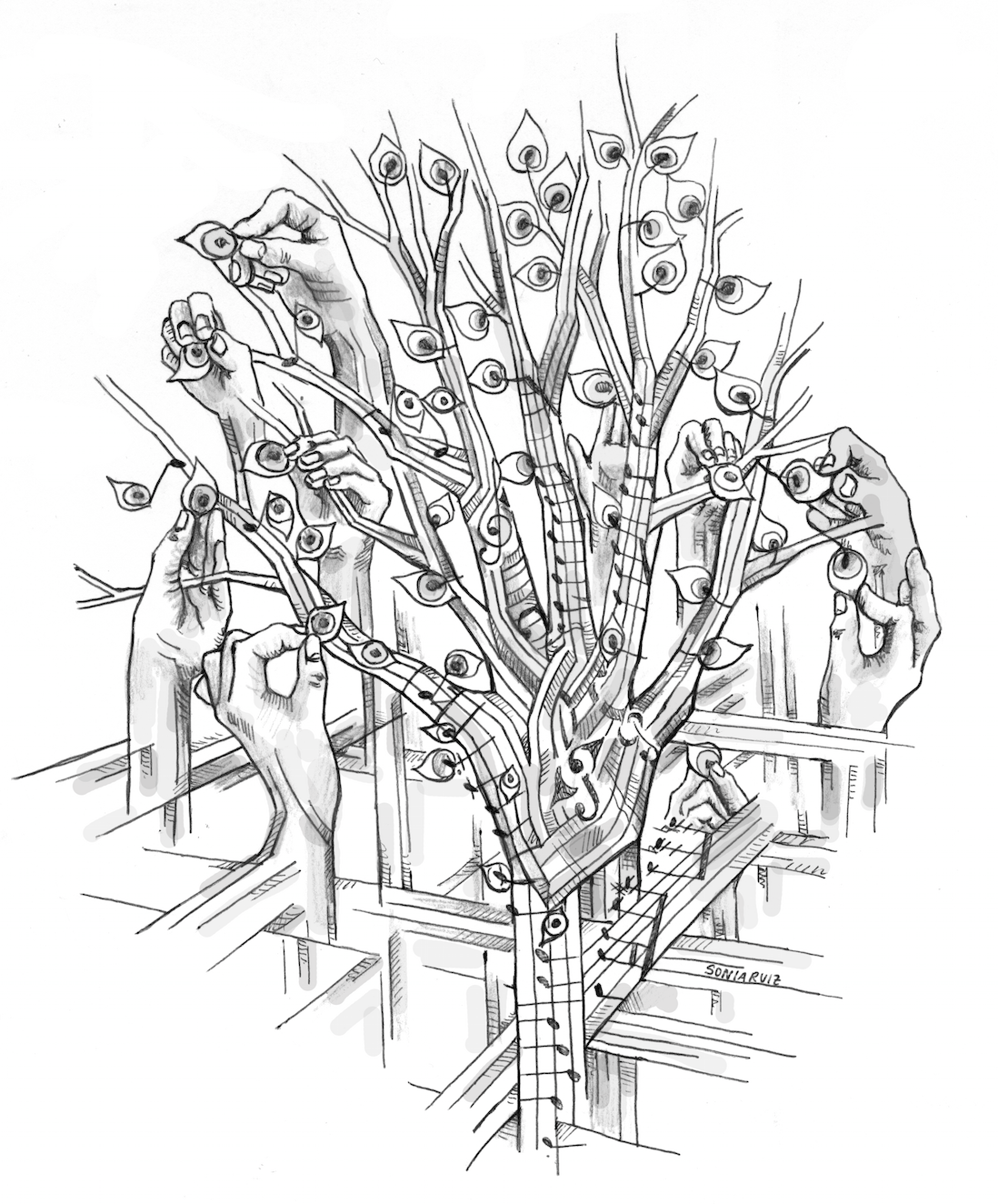

I came to realise that the people around me held a universe in them. I could gain access to these universes simply by listening. In my internship at the Public Defender’s Office, I heard stories from girls and boys my age about how they stole, snorted, punched and wondered what brought them to that side of the table and me to this. In listening to stories from peers from distant backgrounds, I marvelled at the ways they overcame challenges I had never even considered. Walking down the streets, I cringed at every catcall and turned away panhandlers, but thought about how situations produce people as much as people produce situations.

Yale is the most brilliant of universes, but ultimately, it is a closed one. It opened my mind to a multitude of universes beyond my own, but the work it can do for me and for us is limited. There are dimensions I cannot yet fathom beyond these gates, and the quest of learning about these universes continues as we step beyond Yale.

What I wish for myself and for my peers who will graduate with me is that we be comfortable with ambiguity, as we move into universes yet unknown to us. One of the most memorable lessons I learned at Yale, from my philosophy professor, was that an essay need not take one side unequivocally and denounce the other. Sometimes, it can sit in the space of ambiguity and hold two seemingly contradictory truths at once. I know you so well, but you are still unknown to me. I cannot wait to grow up but I want to be twenty-three forever. I earned my place here, but there were factors conspiring to help. We all deserve to be here, but none of us do.

The light on cross campus falls differently in the eyes of Sonia, Julie, Yixuan, Jacob, Marc, Josh, Rachel. Our bodies fold in different ways under the sun. The trick is to see all the universes in this one, including those that are very different from us. And to realise that as much as these universes are next to us, open to us, they remain wholly separate from us, impenetrable to us. We can behold them, come close to them, even enter them, yet never fully be inside of them. Yet I hope we never lose our ability to imagine these universes that are other to our own, to get lost in their unknowable mystery, to give into their gravitational pull and to find ourselves in their orbit.

Kit Lea Cheang | kitlea.cheang@yale.edu