She was wearing a black dress, he thought. Or at least it looked black; in this dimness (“warehouse lighting,” he called it privately, “ambiance lighting,” “all the better to see it with, my dear lighting”) it was difficult to tell. The dress might be navy or brown or purple. In the depths of the dismal Chicago winter, its shine recalled spring nights, raindrops clinging delicately to a flower. She herself struck him as not so delicate. Before, a man had been talking to her and she’d been laughing, not just with her voice but with her shoulders and back and elbows. Exuberance in a black dress. Also heels: She was very tall in her heels, taller than he was. It was possible that she’d be shorter than him barefoot, but in heels she was certainly taller.

She was looking at “Soap Bubble Set” with a little crease between her eyes, the same expression that he himself wore when he shaved with his Schick razor in the mornings. He wondered idly what it would be like to take a razor to “Soap Bubble Set”. The piece itself was just some modernist crap made of wood and metal, irritating and dull. He didn’t know why it was hanging in the Art Institute of all places — the Art Institute, where only estimable artwork should live. “Soap Bubble Set”’s one redeeming quality, he would concede, was its title, which reminded him of that Chardin painting, the one with the young man leaning out of a window and blowing bubbles through a straw. Was that its purpose? to leech glory by evoking a real piece of art? He filed these away among the other questions to which he had no answer, like What is that girl’s name? and how tall would she be barefoot?

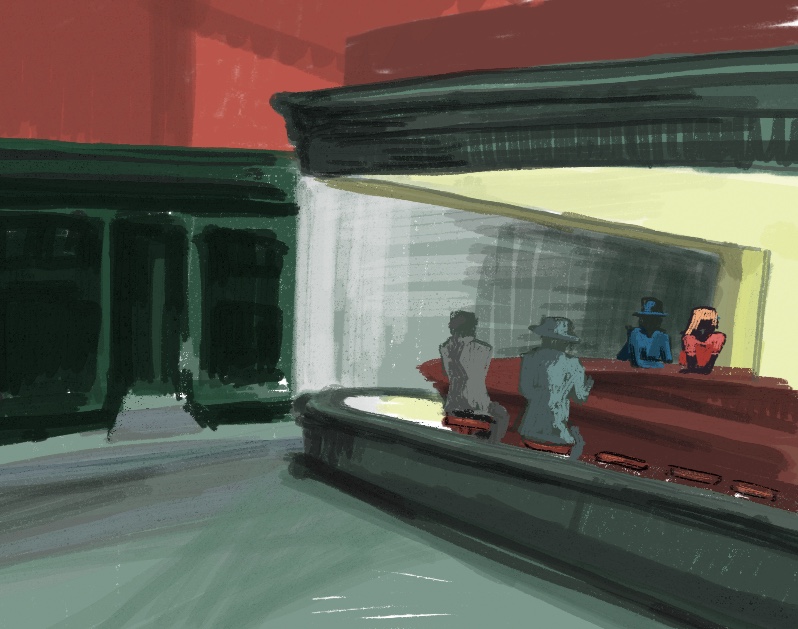

California Boy turned back to the painting at hand: “Nighthawks” by Edward Hopper. There was something solid and quintessentially American about Hopper’s old-fashioned diner, which he secretly imagined as more of a bar. Examining “Nighthawks,” California Boy was convinced that the entire country could be reduced to Hopper’s precise, drab geometries, to straight lines and right angles and perfect arcs. Even the two guys sitting at the bar counter with their fedoras seemed emblematic of something. But what? mused California Boy. American commerce? American success? maybe American morality? There was only one good way to know for sure, and so California Boy opened the door to the bar, stepped inside and brushed down the sleeves of his charcoal suit.

The two men must have been executives, because they were dressed carefully and had the long tapering fingers of men that played catch with money. One was sitting with his back to the door and his face in a tumbler of whisky. The second was rolling a cigarette and leaning in to the woman next to him. California Boy cleared his throat and ordered a sidecar from the white-clad bartender, who stooped obsequiously to sweep the ashes that the cigarette man had knocked off the counter. California Boy sat in the corner seat next to the man with the whisky, hoping to be seen. He thought briefly about striking up a conversation about the suits they were both wearing, which were of similar cuts. But California Boy had never been good at speaking to new people. He didn’t even know what to call the other man – perhaps George? Yes, George was fine, and the cigarette fellow was John, and the woman with the fiery hair was Victoria. At least they would be until they introduced themselves.

Yet in this quiet bar, names felt inconsequential. Silent George could have been Marvin or Peter or Harry and it would not have diminished the confidence of his solitude. And Victoria and John with their gleaming eyes were on the brink of some delicious and anonymous intimacy that California Boy couldn’t fathom.

Some legerdemain of the bartender had produced a sidecar on the counter. California Boy sniffed at it; his throat prickled. He was reminded of his final days in high school, when he and Danny (or was it David?) and some of the other seniors had gone out on the lake. The event was clothing-optional, name-optional and booze-mandatory, that much he remembered. And then there they all were, making drunken — and in his case, discontented — circles on a large raft under the Michigan sun. When he’d fallen into the water and nearly drowned, Danny-David and the rest had barely noticed.

Since then, California Boy hadn’t done anything to avoid lakes, or alcohol. It seemed like a pointless exercise to him, though he took care to only ever drink alone, like now. Though of course he wasn’t really alone. Victoria ran her hand along the grain of the counter and dropped her lipstick; John went to retrieve it. George and California Boy tried not to watch. This revue, he realized, was perhaps something to talk about, an instrument to excavate whatever subterranean rapport might exist between himself and George. California Boy almost did bring it up — “Those two are sure being … public, aren’t they, for total strangers?” But the planes of George’s face were too hard, his nose too forbidding. California Boy kept his mouth shut and picked up the salt shaker. He sipped his sidecar and tilted the white column back and forth, keeping time by its whispers until, abruptly, he felt a tap on his shoulder.

In a remarkable turn of events, it was the “Soap Bubble Set” girl.

“I couldn’t help but notice,” she said to him, running her fingers along the stem of her champagne flute. California Boy knew remotely that the motion was suggestive. Still, he couldn’t make anything south of his waist understand that, because he was preoccupied by the fact that he had neither heard her order champagne from the bartender, nor come up behind him (though she was wearing heeled shoes), nor enter the bar at all. Then he realized that she hadn’t actually spoken a complete sentence, which meant that she was still talking and he should still be listening.

“You — you and this painting. What I mean is, how interested you were in this painting, at least until I interrupted you. It was very noticeable — because there’s no one else in here who looks quite so, um, engrossed.”

California Boy looked around. He thought that they all looked quite engrossed — Victoria and John in each other, George in a stack of papers that he had removed from his leather briefcase, the bartender in his washing up. The salt shaker too: recumbent, dreaming of its hourglass ancestors. There were no paintings around but California Boy didn’t want to mention that right away.

“Sorry about that, by the way,” she continued. “I didn’t mean to disrupt your introspection by commenting on it, but I guess I did anyway. The irony, while truly unadulterated, probably wasn’t worth my gaffe.”

“Don’t worry about it,” croaked California Boy, without really knowing what he was telling her not to worry about. He wet his throat with the dregs of the sidecar.

“It’d be a real shame if you were having deep, important thoughts about this painting, you know, and I barged right in like a bull in a china shop, totally tactless, etc. Is this your favorite one here?”

“My favorite what?” asked California Boy.

“Your favorite painting,” said the girl, as though it were obvious. Now she was smirking at him. It was the incontrovertible pattern of his life. When reduced to a skeleton California Boy’s life was made up of smirking women: American emasculation. (He wished sometimes that a woman would chase him, though it ran contrary to everything that he, with his faint provincial heart, thought he liked. But women never chased him or even seemed to want to, and he didn’t have enough dignity to do any chasing of his own.) She would rout him with that smirk. California Boy turned to George beseechingly, but George had his glasses pushed up to the bridge of his nose and would not meet his eyes. California Boy prevaricated.

“What’s your favorite painting here?” he asked the girl, who had crossed her arms and was now leaning against the counter like the boys from high school who surprised their girlfriends behind locker doors. California Boy thought that the bartender, who was making another sidecar, wouldn’t want women leaning against his counter so cavalierly in their dresses, but the bartender didn’t seem to mind. The girl’s face lit up.

“I adore the Stuart Davis over there. I can’t really describe why, except to say that it looks like, like jazz music!” she exclaimed.

Jazz music was, of course, infinitely more exciting than poor California Boy — born Wilson Eagle Sawyer to a Catholic family with a sensible station wagon — could ever hope to be. He imagined himself in New York, wearing a corduroy jacket and Liam’s face to Jazz at Lincoln Center on Thursday evening. (Liam was in theater and was somehow still the boldest, coolest, most virile guy their age that California Boy knew. He was hard to share a room with but often quite easy to hate.) That version of California Boy would have something to say, but this one was out of his element.

“That’s very interesting. An interesting take. I think it’s— ” California Boy began.

“Interesting?” she remarked archly, draining her champagne glass. When she looked back at him California Boy saw that one of her earrings had caught in the collar of her dress. (A black dress, he confirmed, although the unforgiving fluorescence washed it out slightly to gray.) He felt buoyed; he could withstand any number of “Interesting?”s if her earring remained ensnared.

California Boy tried to play it cool. He rolled some of his drink around on his tongue speculatively. Not even 10 years ago he had done the same with Jolly Ranchers on Halloween. He would reach blind into the pillowcase and take two out, unwrap them, place them both in the center of his tongue. Then the guessing began. Watermelon and Cherry? Sour Apple and Cherry? or two Blue Raspberries? He thrived on the diversion, mostly because it made the candy go faster so that his mother wouldn’t catch him, rainbow-tongued and guilty, somewhere in the vicinity of Thanksgiving. But the game also carried an attendant drama: He was training himself to be a chef, perhaps, or a food taster for a king. He’d wanted, in that hackneyed pre-adolescent way, for every mundanity of his life to impute to something larger than himself; he had always confused metaphor and metonymy.

Meanwhile, the girl had unscrewed her earring back and disengaged the offending hook. She removed the other earring with a flippant “They’re such a pain to wear,” placed them in her bag and drew out a business card. He was stunned that she had one. It had never occurred to him that business cards were a necessity looming on his own horizon.

“Here you go. I hate introductions, but cards — now cards are so compact,” she said, waving her hand airily. She didn’t give her card to George or John. California Boy wanted to be flattered, and suppressed his suspicions that they both were more handsome and wore better cologne.

“Lina Menon,” he read. He treaded carefully over the foreign syllables. He guessed that her family was from India, though that wasn’t on the card. What was on the card was the name of her school — LSA at Michigan! — and her major, which was biology.

“It’s good to meet you, Lina Menon. I go to Michigan, too,” he said, “only I’m in Chicago for break.” He could hit himself. Of course he was in Chicago for break. She was in Chicago for break too, clearly. What he had meant to say was that he didn’t live in Chicago and was only visiting. (Liam was putting him up, though it seemed foolish to depend upon the hospitality of a guy who was frequently his greatest enemy.) He had also meant to get the word “Saugatuck” in somewhere. Not that he believed for a second that she would know where Saugatuck, Michigan, was, though the population swelled to a whole 3,000 in the summer months.

“Really? I live here — or at least, I live in Lisle. I’m a biology major. But whoops! that’s on the card.”

California Boy didn’t mind that it was on the card. He found that he liked hearing it directly from the source and would hear it a second time if only to keep her talking. Her voice was marvelous, a low serene rumble like the echoes of the ocean through a conch shell. (Even the shells he’d collected from the side of the lake as a boy didn’t sing lake stories but longer, older ones. It was a genetic thing, he guessed, a primal instinctive thing, that all shells, whether they know it or not, are seeking out the ocean.) Liam, always debonair, would have said so: “You’ve got such an expressive voice.” But California Boy couldn’t allow himself such a vulnerability. How could he bare his own dreaminess and fancy to a stranger he had only just met in a bar, even in the form of a compliment? Therein lay the difference between California Boy and Liam. Or between California Boy and John, for that matter. John, who was just now whispering something in Victoria’s ear. California Boy shifted to block John’s view of Lina. He felt sure that John was the type of man who always pursued the prettiest woman in the room, and Victoria, with her disdainful eyes and audacious crimson mouth, could not hold a candle to Lina.

Lina had mentioned her major. Biology, which was left-brained enough to intimidate. And she’d worked it into the conversation herself. California Boy felt a little panicked, because of the incontrovertible pattern. She was drawing him out, when everything he knew about boy-girl interactions (admittedly, rooted in his observations of Liam and the Saugatuck senior class) told him that he should have been drawing her out. He clawed for something to say and decided to identify himself in turn.

“California Boy,” he said. She took his right hand firmly in her own and shook it. Of course she had a firm handshake.

“California Boy,” she repeated. It dawned upon him that he could have introduced himself as Wilson. He’d had the opportunity to jettison his ridiculous epithet, and he’d missed it. He was an idiot. Why had he said what he said? and what more did she want from him? and why did he feel sick?

She looked at him inquisitively, as though she wanted more. To know, perhaps, what did he do? He could not tell her that he did hardly anything, compared to biology.

“I study art history,” he said. He glanced at George, whose brow was furrowed over a yellowed contract. A finger of whisky still glistened in George’s tumbler; California Boy wondered fleetingly if he could snatch it up for himself. Meanwhile, John and Victoria sat with their hands nearly touching. The world was made up of royalty, he realized, of George and John and Victoria who traded in expensive clothes and exclusive silences, overlooked the canaille they drank with. And the world was busy; there was no more room left for him.

“Oh!” She giggled. It seemed like nerves. Nerves? “Art history. That sounds difficult. I’m actually pretty terrible at history and at responding critically to art and music and things like that. My viscera just don’t seem to want to do it. Is it really hard, to have to come up with something new and really formal to say about this painting or that sculpture every time?”

Lina was rubbing at her collarbone with her right thumb. In someone so invincible even the slightest tic was obvious, and California Boy felt suddenly triumphant. Somehow, he had discomfited her! His sense of sexual urgency, shameful and eager, came swinging back like a pendulum over sand, pulled toward the new locus of his hopes and desires that beat in her sternum. He drummed his fingers on the cherry wood of the counter.

“It’s hard,” he said, with some boldness. “It’s hard, but it’s not as hard as it could be. It’s less memorizing than you’d think. I mean, dates are important, but knowing the theories and the movements and being able to synthesize everything is probably more important.”

“I’m good at memorizing,” admitted Lina. “That’s why I’m a biology major. It’s all memorization. The hydrolysis of the terminal phosphoanhydridic bond is exergonic and so forth. It sounds pretty ghastly but if you can remember the terms you can do biology. ‘Synthesizing,’ as you say, is for the chemists. Anyhow, what’s the best painting you’ve ever seen?”

Heartened by this line of questioning, California Boy chose to ignore “the terminal phosphoanhydridic bond.” He thought instead of the Kunsthistoriches museum in Vienna.

“I like Vermeer. ‘The Geographer,’ ‘Pearl Earring,’ obviously, ‘The Milkmaid.’ ‘The Art of Painting,’” said California Boy.

“‘The Art of Painting’? I’ve never heard of it. I’ll be the first to say that I’m pretty uncultured when it comes to paintings, especially all that Dutch stuff,” said Lina, with a little sheepish twinkle.

California Boy felt better.

“Oh!” she cried. “Wait! Here I was, telling you that the Davis looked like jazz. I’m sorry. Now I’m just embarrassed. It must be really irritating to have people tell you things about art that make no sense at all.”

California Boy struggled to quiet the humming of his blood and think of something to say to this. He tried: “I don’t listen to much jazz, but if you come back to my apartment we can put some on and find out exactly what you mean.” He tried: “I definitely feel that way reading Jansen’s ‘History of Art’ sometimes.” He tried: “Better you than my rich, white, old, heterosexual, Eurocentric male Renaissance art professor.” He tried: “No one as beautiful as you could ever be irritating.” He tried: “There’s no need to apologize. I don’t know a whole lot about jazz, but even I can tell that your description is really fitting.”

Nothing was quite what he wanted it to be, and yet she would only wait so long for a response before leaving. California Boy righted the salt shaker and flicked its side to settle the surface of the white. As he racked his brains, the bartender, who was rinsing a martini glass in the sink, flashed him a sympathetic smile.

The smile was California Boy’s undoing. He had been getting along so well until now, had been only a few seconds from making his romantic overtures. If only he could exist in a vacuum, where no one (certainly not this pointy-faced bartender, clearly a replacement, still wearing his busboy cap) would smile at him as he tried to pick up a woman! California Boy felt like a plant whose sun is removed from the sky without any warning: What can it do but wilt?

“Maybe,” California said, and the overhead lights flickered. For a moment he saw his shadow against the opposite wall, a broken marionette dissolving into the margins of the countertop; he saw her shadow, dancing its mocking beguine; and where he should have seen the impersonal afterimages of the Nighthawks there was nothing at all.

California Boy needed to be severely inebriated, right now. He ordered another sidecar from the bartender with a glare and remembered that Lina was the first girl with whom he’d had any kind of conversation in the post-bellum era — the post-Sophie era. As he waited for his drink California Boy watched the spring raindrops that winked against the satin of Lina’s dress. They ran one by one into the hollows where the material was crumpling against the barstool, oblivious to his agony. Why had no one noticed Lina? and why hadn’t she hadn’t gone away yet, or taken up with that Casanova John, or George, or even the bartender? and did he have enough cash in his wallet to pay for all the drinks he had ordered?

Lina opened her mouth. In that instant he recognized why she had stayed. She liked it. Whatever awkwardness had blossomed between them, she liked it. She had the upper hand again and she liked it. California Boy blinked and shook his head. He thought abstractedly that he could hear the snow piling up in the streets.

“Do you want to —” she began. She hesitated, and he narrowed his eyes at her. (It was the only way he could focus on what was coming next.) “Do you want to get out of here?” she asked him.

Somewhere in Chicago a church bell was ringing, sending circular bronze vibrations through the night; somewhere a flame had been snuffed out, a lamp turned off. The roads were quieting, soothed to sleep by the falling snow. California Boy took a deep breath, nodded, extracted his wallet from his breast pocket and opened it to count out enough money to cover — but there was no bartender and no bar. There was only the Hopper behind him and the red-white-and-blue Davis on the adjacent wall. The patriotic Davis, thumbing its nose like jazz at the Hopper.

People slowly trickled out of the Art Institute back to their apartments, and Lina stood on the gallery floor next to him. Sickness burgeoned again in California Boy’s stomach. She would, he decided, be taller than him in flat shoes as well. Not by much, but it was enough.

He put his wallet back into his suit jacket. Then he took her arm and led her away to find a cab.