Samuel Turner

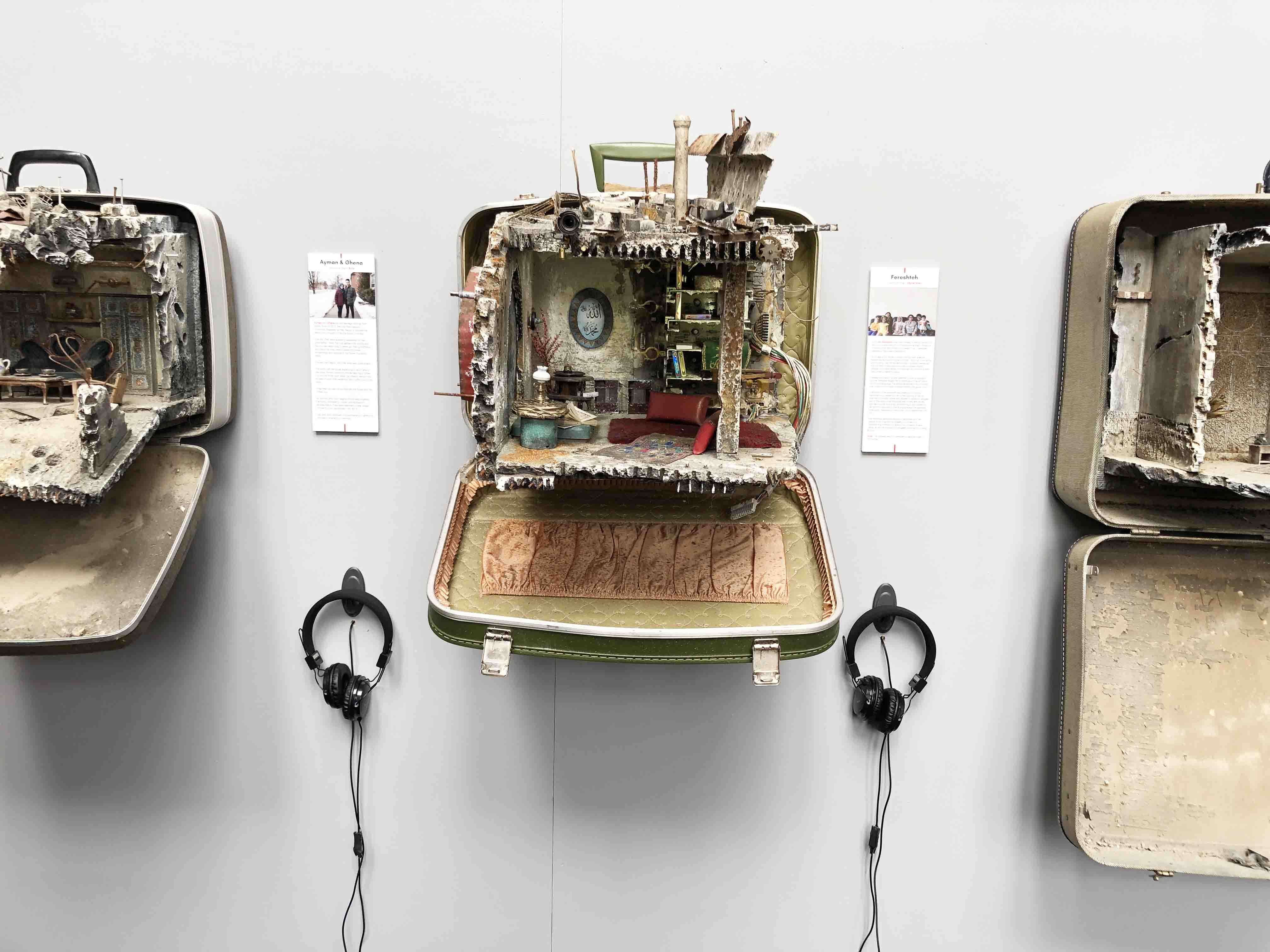

Scenes of immigrant families, built out of suitcases, line the walls of the Lillian Goldman Law Library as part of a sculpture exhibit — “Unpacked: Refugee Baggage” — organized by the Orville H. Schell, Jr. Center for International Human Rights to highlight the stories of refugees.

New Haven artist and architect Mohamad Hafez — a fellow at Silliman College — created the exhibit in 2017 along with Iraqi-born writer and Wesleyan student Ahmed Badr. In this exhibit, Hafez used the inside of suitcases to sculpturally recreate the rooms, homes, buildings and landscapes that have been ruined by war. Each suitcase is accompanied by an audio recording of the voices and stories of real refugees — from Afghanistan, Congo, Syria, Iraq and Sudan — who have escaped those rooms and homes to start a new life in the U.S.

“The refugee crisis has been going for a long time now, and it is portrayed in the media in more of an abstract way — talking about politically, in abstract numbers,” Hafez said. “I saw this exhibit as a way to humanize refugees.”

Hafez will be speaking at the 21st annual Bernstein Human Rights Symposium on April 4 and April 5. The symposium invites current and former fellows with the Robert L. Bernstein Fellowship in International Human Rights to engage in human rights discussions. Hafez and Badr’s work will be on display throughout the conference.

The exhibit has been on display since October 2017 at locations ranging from The Juilliard School to the UNICEF House across from the headquarters of the United Nations.

This is not the first time that the Law Library and the Schell Center have collaborated on projects at the intersection of art and political advocacy.

In 2017, the Law Library hosted “Inside the Box,” an interactive, life-sized confinement cell that simulated what life was like in solitary confinement, along with the National Religious Campaign Against Torture.

The 10 refugee families interviewed by Hafez and Badr currently live in New Haven.

Hafez, who immigrated to the U.S. to study architecture, is currently unable to go back to his home country, Syria, because of the war there and the travel ban imposed by President Donald Trump.

“This exhibit is an amazing model of art and storytelling because it give refugees themselves the platform to tell their own stories when they’re so frequently having their stories narrated without themselves having any agency in the process,” said Charlotte Finegold, who works as a Community Human Rights Fellow at the Schell Center.

Finegold said that the “ravaged dollhouse miniatures” affect her the most because of their contrast with the dollhouses she loved as a child.

For Associate Law Librarian for Administration Lisa Goodman, who helped coordinate the location of the exhibits, the exhibit has required multiple visits.

“A lot of my colleagues in the library and I have to do a few suitcases at a time, come back, and do some more later because some of the stories are really difficult to hear and to process,” said Goodman.

For his next project, Hafez plans to focus on “humanizing” immigrant communities.

“I am interested in uniting people through artwork and highlighting the common denominators between different cultures and peoples,” Hafez said. “In my experiences living throughout the world, there is so much xenophobia, Islamophobia and fear mongering.”

The Bernstein Symposium began in 1997 in honor of Robert Bernstein, the founding chair of Human Rights Watch.

Samuel Turner | samuel.turner@yale.edu

Correction, April 5: A previous version of this story said that both Badr and Hafez are speaking at the Bernstein Symposium. In fact, only Hafez is speaking at the event.