On Sunday, cellist Steven Isserlis and pianist Robert Levin performed a sold-out concert at the Yale Collection of Musical Instruments on Hillhouse Avenue. The performance, part of the collection’s annual concert series, comprised works for cello and piano by Ludwig van Beethoven. The program spanned the length of the 19th-century composer’s career, showcasing the evolution of his compositions.

Levin and Isserlis — who was knighted in 1998 in recognition of his services to music — opened the performance with Beethoven’s Cello Sonata No. 1 in F Major, Op. 5. This sonata was the first major cello sonata with a written-out keyboard part — an aspect of the piece that diverges from previous sonatas, which include a complete cello part and only basic chord progressions for the accompaniment. Beethoven’s final cello sonata, the Sonata No. 5 in D Major, Op. 102, concluded the first half of the program.

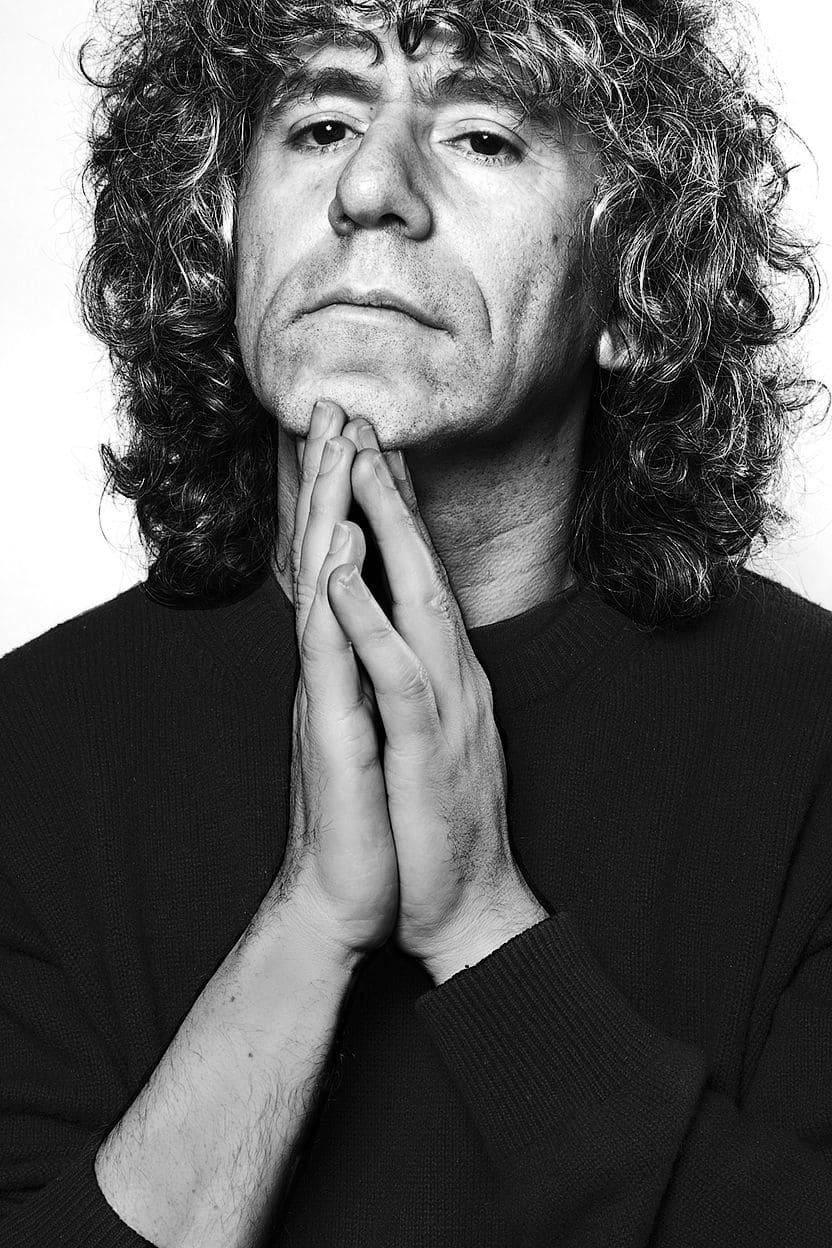

Isserlis, who is one of only two living cellists featured in the Gramophone Hall of Fame, impressed concertgoers with his musical and technical abilities.

“[Isserlis] has a tremendous sense of narrative in his phrasing … it is obviously very considered,” said audience member and cello student Gabriel Rainey ’20. “The balance is fantastic with these instruments — his control over every aspect was really wonderful.”

Other audience members also praised Isserlis’ musicianship.

“I thought it was stunning, the way Isserlis is just about the music … even though he’s technically spectacular, he’s only thinking about the music,” said concertgoer and cello student at the School of Music Samuel Walter MUS ’20. “Just his abilities to get soft pianissimos is out of this world and makes it really magical — it was so dynamic.”

The second half of the program opened with Beethoven’s 12 Variations on “Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen,” a piece based on Papageno’s aria from Mozart’s 1791 opera “The Magic Flute.” The performance concluded with Beethoven’s Cello Sonata No. 3 in A Major, Op. 69: the most popular of Beethoven’s five cello sonatas, according to Isserlis’s program notes.

Concertgoers also enjoyed Isserlis and Levin’s historical approach to their performance, which featured a fortepiano, a predecessor of the modern piano, designed after one of the collection’s own instruments. The original fortepiano, built around 1830 by Austrian piano maker Ignaz Bösendorfer, is similar to the sorts of instruments musicians during Beethoven’s time would have played.

“I absolutely loved hearing [the repertoire] with the fortepiano and the period approach,” said Rebecca Patterson, concertgoer and principal cellist of the New Haven Symphony Orchestra. “It opens your eyes to the sound that you would’ve heard.”

Collection of Musical Instruments Director and School of Music faculty hornist William Purvis elaborated on the instrument’s unique history.

Purvis described the instrument as “a sort of touchstone.”

“The Bösendorfer is really quite a special instrument. It might be, in a way, one of the most fragile instruments in the collection. It sat in a mansion in the South of the U.S. for about 100 years in a humid climate, detuned and not played,” Purvis said. “So when it came to the collection, pretty much every part of that piano was original and still is.”

In addition to the fortepiano, Isserlis performed on his “Marquis de Corberon” cello, created by famed Italian violin maker Antonio Stradivari in 1726. For the performance, Isserlis chose to string the cello with gut strings — strings made of tightly twisted sheep intestines historically accurate to Beethoven’s time and earlier — rather than contemporary metal strings. Isserlis also chose to tune his cello to a lower pitch than is used in modern performances to better reflect the sound of the early 19th-century.

The historical focus of the performance, however, did not come at the expense of the music. Purvis said that he enjoyed that the performers used historically informed practices yet were still dedicated to conveying the meaning of the music to the audience.

“These are two musicians who have really done a lot of research and who know a lot about historical performance, but the main point is what compelling musicians they both are — individually and as a duo,” Purvis said. “I find their partnership really quite interesting — the way they play off one another and the dialogue between them is really fascinating and quite inspiring.”

The Collection’s next and final concert of their 2018–19 series will take place on Sunday, March 31.

Matthew Udry | matt.udry@yale.edu