What to do with a dead abuser? My high school, an all-boys Jesuit school, seems to be trying to figure that one out. The Jesuit Northeast Province recently released a report of over 50 priests from dozens of schools and parishes who have been identified as abusers. The numbers are truly frightening. The reports go back to the 1940s. Some are as recent as 2008. There are often decades between dates of incidents and dates of reports. All the while, generations of boys learned, graduated and forgot. My school makes the list upward of seven times and while no recorded incidents for said priests occurred during their time at my high school, they walked the halls, taught classes and shaped the lives of boys like myself all the same.

This isn’t new. We’ve all heard about the massive cases, while thousands of the individual cases, cover-ups and scandals have dotted the map and flown under our radars. And while the school community knew that these cases were out there, we never expected them to hit so close to home. It was foolish to think that we would escape it, but that’s always the hope when engaging with a flawed institution: that your iteration of it can exist without the baggage of its larger structure. Wishful thinking.

There are many outcomes that can occur when a Jesuit is credibly accused of misconduct: incarceration, impediment, laicization and departure from the order are a common few.

Of the 50 Jesuits on the list, 35 are deceased, with the vast majority having died before their abuses went recorded. Now that these men are six feet under, most of them long-deteriorated, are we to exhume their corpses? They’re dead. It sickens me to know that these predators will never face the music. Or will they? “To those who abuse minors, I would say this: Convert and hand yourself over to human justice and prepare for divine justice,” Pope Francis declared in a speech this past December. In the eyes of the church, the afterlife is a real place, capable of punishments greater than anything an orange jumpsuit can deliver.

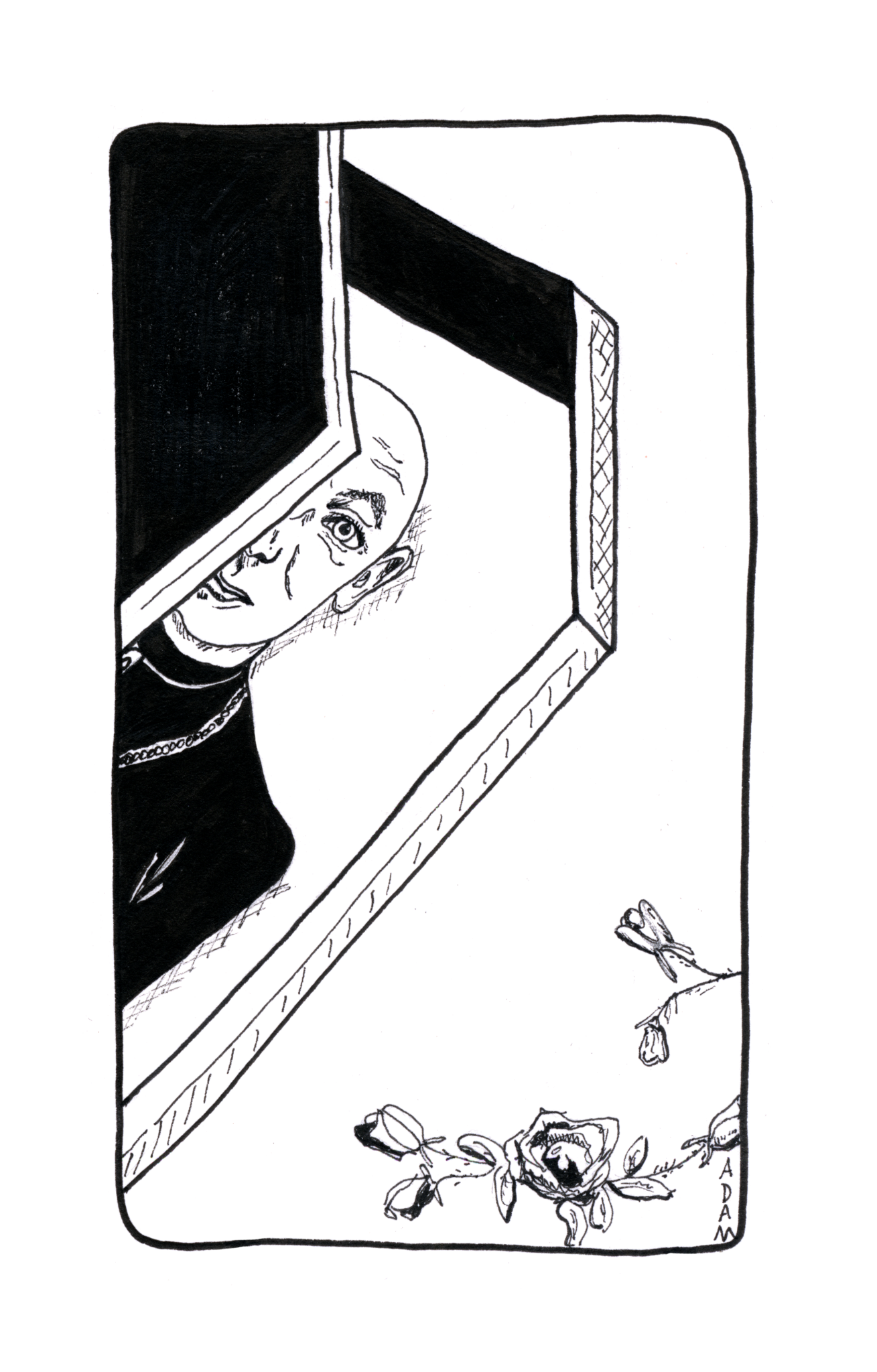

But for those who don’t subscribe to that cosmic view of justice — and even for most who do — that is not enough. It can feel pointless to hate the dead, to want to shout at those who will never listen. But even if these priests are not alive somewhere in the afterlife, they’re not really dead. Their crimes, their lack of punishment, live on in the trauma of their victims and the structures that permit new victims to be made and new abusers to get away with it.

Of the 50 on the list, only two priests were incarcerated. Eight left the order voluntarily. Only one was laicized. When a priest is laicized, their vows — including celibacy — are reversed and they become a layperson again. Eighteen were impeded. When a priest is impeded, they are removed from their duties as a priest but remain in the order. That matters.

As trivial as it sounds, this crisis is not merely political. The Catholic Church is not only a $30 billion international organization with 1.2 billion members headed by the sixth most powerful man on Earth. It also happens to be the messenger of the universal truth handed down to us by God. A priest is not merely a community leader. He is “a mediator or ‘bridge-builder’ between God and humanity.” Thus, even if he can no longer say mass, even if he is “prevented from fulfilling his pastoral function in the diocese, so that he is not able to communicate with those in his diocese even by letter,” he is still endowed with a divine position between humanity and God. He is still a holy man. Impediment is a seemingly political answer to a problem that the Church believes is rooted in something much more cosmic.

I recently sat in on a conference call with the school president, a Jesuit and a few alumni, one of many opportunities for dialogue the school has put forth in recent weeks. Admittedly, the school itself is tackling the issue head on. My principal spoke in blunt condemnation of the crisis, reiterating statements made in communitywide emails and detailed a slew of initiatives the school has implemented in recent years: an adoption of new standards that are stricter than the church’s 2004 “Dallas Charter”; an ongoing relationship with an external protection agency; intense background checks on faculty; and yearly training. At a time when the popular image of all-boys Catholic schools lies somewhere between Kavanaugh and Covington, the school has upped the number of “prayer services” in lieu of formal masses, prayer services that often feature female teachers’ reflections in lieu of homilies. Not being Catholic myself — attending the school on scholarship — I always tried to separate a Jesuit education from its Catholic foundation. But the school cannot do the same. Just as the church cannot differentiate between solutions political and divine, its issues cannot be solved by dropping adjectives or only looking inward, when legacies of patriarchal and colonial pasts stain both the secular and religious adjectives that make up an all-boys, Catholic school.

Keeping your house clean is not enough when there are bones out back. For as long as crosses hang above the doorways of my high school, the entire church will be its backyard. The church needs questioning of its millennia-old authority, it needs serious reconciliation — it needs cleaning.

I’m currently sitting on my dorm room bed writing this piece, tired from hours of hacking away at feelings that come easier than their corresponding thoughts. In one beautiful, terrible place scarred by its crimes, I’m writing about another. I’m sporting a white-on-blue sweater with a big “Y.” I haven’t been to church in years. But underneath, I’m wearing a ratty, old spirit day T-shirt from my sophomore year of high school. For as long as we continue to enjoy this beautiful, horrible, complicated world, we need to keep digging up its dead abusers. More often than not, they’re still breathing.

Eric Krebs is a sophomore in Jonathan Edwards College. His column runs on alternate Mondays. Contact him at eric.krebs@yale.edu .