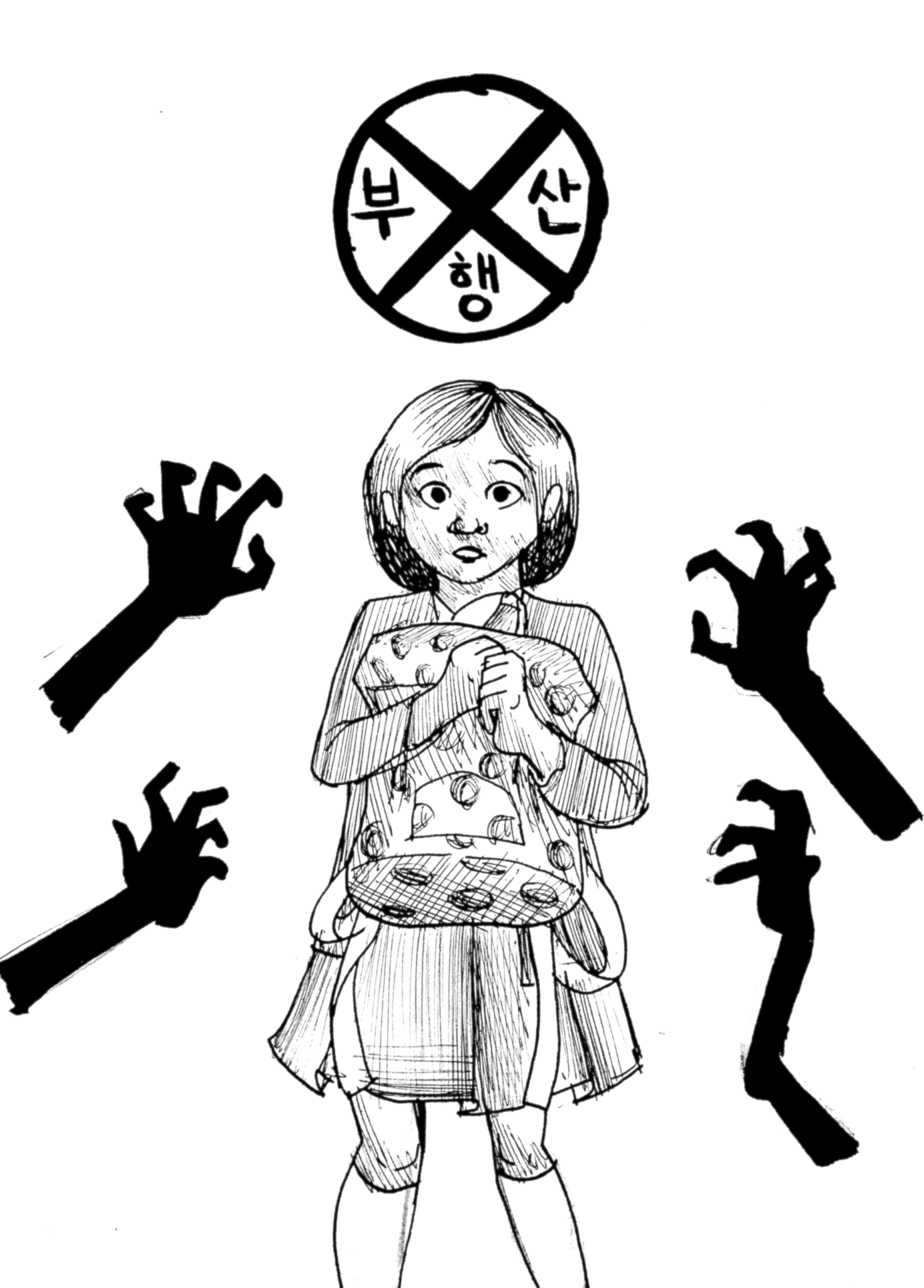

Yeon Sang-Ho’s “Train to Busan” is a well-paced zombie apocalypse thriller that moves lightly, tramples on your emotions and, ultimately, delivers a wholly satisfying cinematic experience. Set in Korea, the film follows divorced fund manager Seok-woo — played by the popular Korean actor Gong Yoo — and his daughter Su-an as they take the eponymous train from Seoul to Busan in order to visit Su-an’s mother. Just before the train leaves the station, unbeknownst to the passengers, a disheveled and purple-veined woman slips aboard. Thus begins the intrigue and body count.

As with any good zombie drama, “Train to Busan” is less concerned with the mechanics of the undead apocalyptic disaster and more interested in delving into the psychologies of the various characters trapped within its hellish world — in this case, the tight confines of a high speed train. At the start of the journey, viewers are quickly moved through the passenger train cars and introduced to key players: a pregnant woman and her dedicated husband, two elderly sisters, a high school baseball team and a homeless man, who, having experienced the zombie attack firsthand, stumbles onto the train and hides inside a bathroom stall.

Though each of these characters develop distinct stories that become inextricably woven together, the heart of the film is the relationship between Seok-woo and Su-an. An absent father preoccupied with work, Seok-woo makes minimal effort to connect with his daughter. The lack of connection becomes most apparent in their interactions with others, especially as the tension ratchets up with zombies rapidly spreading throughout the train. Seok-woo looks out only for himself and his daughter, keeping valuable information of the outside world to himself, while Su-an reaches her arm out to fellow passengers and readily offers her seat to one of the elderly women. Over the course of the film, though, Seok-woo undergoes serious character development as he is saved by others and learns to care for them in turn.

While the zombies are by no means the focus of the film, they are wonderfully rendered with their milky eyes, purple veins and back-bending, jerky movements. Like those in “World War Z,” these walkers are endowed with inhuman speed, propelled forward in swells of clambering limbs and bloody maws, as if part of some mutant superorganism tripping over itself in a state of frenzied animation. However, the speed and movements of the zombies are the limit of similarities between “World War Z” and “Train to Busan.” Sang-ho’s film cultivates character development and emotional texture not found in the American blockbuster.

The fight scenes amongst the living and undead are suspenseful and well done, particularly during the shots of Seok-woo and two companions fighting their way railcar by railcar through milling masses of zombies in order to reunite with their loved ones. The trio — armed with baseball bats and duct tape protecting their arms — whack, punch and shove their way through, landing hits with cathartic force.

Amidst all the seriousness, the film has brief comic asides, providing breaths of relief. Whether through funny banter — such as when one passenger warns Su-an that she should study hard, lest she end up like the homeless man — or close-up shots of individual zombies with their faces contorted and bloodied, the humor is welcome.

At times, certain characters seem to fall into tropes, leeching them of depth. In particular, a self-serving businessman — who serves as both the foil of Seok-woo and the one true villain in the plot — felt one-dimensional in the callous way he shoves others in the way of harm in order to protect himself. Even so, in his role as demagogue, he provides plot interest in bringing out the worst in those around him, promoting a dog-eat-dog mob mentality.

As the film moves to its climax, the emotional ploys, emphasized by a crescendo of violins, felt overwrought. What ultimately made the film for me, though, is what followed the climax. Delivered with a simple song, the denouement unfurled, leaving me devastated, as the tune provided salvation for the characters left standing, while also reminding viewers of the emotional journey undertaken and the innocence lost.

“Train to Busan” has a runtime of 119 minutes and can be found on Netflix.

Selena Lee | selena.lee@yale.edu