Yale Divinity School

Lamin Sanneh, a Yale Divinity School professor known for his scholarship in world Christianity and African history, passed away on Jan. 6 after suffering a stroke. He was 76.

According to a Jan. 7 message from Divinity School Dean Greg Sterling to the Divinity School community, Sanneh’s death was “sudden and unexpected.”

“Everyone is in shock,” Sterling told the News. “We were all with him at different events in December … he was his normal, jovial and good-humored self, so it was just a complete shock.”

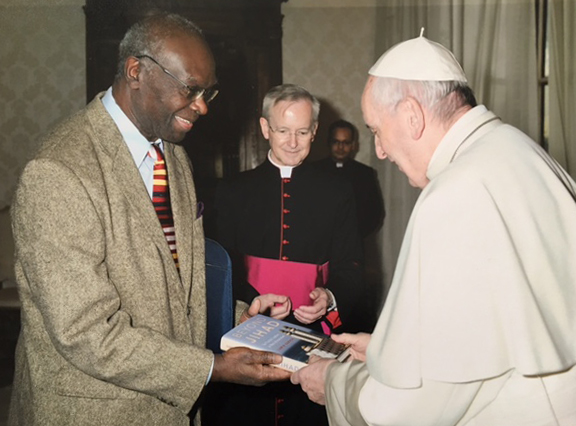

Hailing from MacCarthy Island in Gambia, Sanneh, a descendent of ancient African royalty, was raised Muslim and later converted to Roman Catholicism. He came to Yale Divinity School in 1989 after serving on the faculty at the University of Ghana, the University of Aberdeen and Harvard University.

During his time at Yale, Sanneh served on the board of Overseas Ministry Study Center and served as the “key link” between the center and the Divinity School, according to Sterling’s statement. Sanneh attended St. Thomas More Catholic Chapel and Center and served as an honorary member on its Board of Trustees. As the author or editor of twenty books and over 200 academic journal articles, Sanneh wrote prolifically about African history, abolitionism, missions and Christian-Muslim relations.

“He really was a believer in the power of scholarship — in the idea that by learning things, by deeply understanding things, you can transform your life, and you can transform the world,” said his son, Kelefa Sanneh. “He did a lot of work on Muslim-Christian dialogue, and that was a message that he returned to again and again, that so much change is possible if we think deeply about our history and look deeply into these religious traditions that shape the way people live around the world.”

In interviews with the News, Sanneh’s colleagues highlighted his knack for fostering interfaith dialogue and promoting a more expansive, global view of the Christian faith.

Andrew Walls, a British scholar of missions and religious studies who knew Sanneh for decades, explained that in the past, studies of Christianity had an “unconscious association with Western civilization.” Walls said that Sanneh made “enormous contributions” to his field by “illustrating the extent to which Christianity is now, in the 21st Century, principally a non-Western religion.”

“He came from the continent where the Christian faith is growing by leaps and bounds right now, while we here are talking about a sustained decline,” said liturgical studies professor Teresa Berger. “His experiences were invaluable in a divinity school looking ahead to what the future might hold.”

Berger added that, given “his scholarly stature and personal experiences,” she does not “think there is anybody in the world right now who could fill that void” left by Sanneh’s passing.

In 1992, Lamin and Walls established the annual Yale-Edinburgh Group on the History of the Missionary Movement and World Christianity conference, inviting distinguished international scholars to each university to promote discourse about the development of world Christianity and the historical aspects of the missionary movement.

“He was brilliant — that was the bottom line,” said Martha Smalley, former special collections librarian at the Divinity School who worked with Sanneh on the administrative side of the Yale-Edinburgh conferences. “He was a real draw of the conferences in many ways because he had the ability to make people think about things in different ways. I heard him referred to as the ‘architect of the discourse’: He would change questions or make people think outside of the box about things.”

Smalley added that she can imagine that this year’s conference, set to be held at Yale this June, will serve as “a place where we people will want to come and reflect with others about [Sanneh’s] legacy.”

Divinity professor Harry Attridge, a member of the Saint Thomas More Board of Trustees and former dean of the Divinity School, said that Sanneh brought a “global perspective” to the Catholic community at Yale.

“We tend to think about things happening on the ground … he was kind of a reminder that the student population is going to be engaged in something bigger than the neighborhood in New Haven,” Attridge said.

Attridge added that Sanneh was “a major presence over the years bringing to the table the issues of and the methods for engaging Christian-Muslim dialogue” at the Divinity School. While the school focuses on Christianity, Attridge stressed the importance of educating future Christian church leaders in interfaith engagement.

Last year, the University of Ghana established the Lamin Sanneh Institute in recognition of his scholarship on the relationship between Christianity and Islam in Africa. The new multifaith and multidisciplinary institute will focus on designing research projects to examine the interactions between religion and society in Africa and providing a platform to share the results.

Walls stressed that Sanneh was adept at building “frameworks” that would live beyond his own life. The Sanneh Institute, Walls said, is an opportunity to “give institutional form to his work.”

Beyond his scholarly contributions to his discipline, Sanneh’s colleagues also emphasized that he contributed to the Divinity School community with his likable personal qualities.

“He was very personable and genteel, and he had many friends in the community,” Smalley said.

Berger, who also attends St. Thomas More, called Sanneh “unfailingly kind.” When Berger missed several weeks of worship services at the parish because she was traveling, she recalled Sanneh telling her after she returned that he was concerned about her absence and had asked other parishioners if she was alright.

Sterling characterized Sanneh as a “person of good sense of compassion and quiet thoughtfulness” who always thought deeply and offered perceptive commentary.

“There are many great faculty at Yale which makes Yale, Yale,” Sterling said. “Lamin was one of those, but he was also a great human being. And the fact that he was a great scholar and a great human being endeared him to all of us.”

Sanneh is survived by his wife, Sandra GRD ’93 — a professor of isiZulu at Yale and the director of the Yale African Language Initiative — his son Kelefa, his daughter Sia LAW ’07 and two grandchildren, Ronald and Doc.

Sanneh’s funeral was held on Saturday, Jan. 12 at 11 a.m. in the Divinity School’s Marquand Chapel.

Asha Prihar | asha.prihar@yale.edu