Valerie Pavilonis

Eds: This essay references topics related to suicide and self-harm.

It’s strange how one person’s empty locker 800 miles away can make you cry.

Because you didn’t know him, never heard him speak, never knew what his voice sounded like or how he walked. What his laugh was like, or the way he smiled. But now it’s too late, because he’s dead.

One of my friends asked me about the flurry of Snapchat and Instagram stories, about why everyone from my high school had suddenly posted a sign that read “We Love You.” Words failed me, because even the news of suicide is a shower of bullets, and I didn’t want to shoot yet another bystander full of bruising holes.

My high school lies on Chicago’s South Side, a red-bricked building that, for the most part, stands quietly and without incident. Such a peaceful environment made for a spectacular experience, and while at Yale I’ve heard many bemoan their high school years, my good fortune allowed me to enjoy nearly every moment I had within its humble halls.

Often in religion classes, we would discuss the violence-riddled neighborhoods of Chicago, and how, after hearing about deaths every day on the TV or the internet, we had become desensitized to violence, to the point where news of people shot last weekend elicits no other reaction besides a tired sigh. But no one was sighing when we heard back in October that a beloved senior at my high school wouldn’t be returning on Wednesday. Or ever again.

My school’s proud motto is “Brothers and Sisters for Life;” from our first day as freshmen, we are told to support each other, to love each other as family. So even though I had never met the student, news of his death, which creeped in as I slowly realized what had happened, affected me more profoundly than I could have ever predicted.

It wasn’t just me. My classmates, all of whom graduated and scattered as I did, posted and reposted those same words: “We Love You.” Friends who had caught far-reaching planes from Chicago to Arizona, Florida, Alabama and every place in between suddenly came home — if not physically — to mourn the loss of one of our own. We were far away by many miles, yet the waves of support flowed through each of our phones, sending ripples of sympathy from every screen to every heart.

Hope in the shadowed face of death cannot be ignored in tragic times. When Thomas Lawrence ’21 passed away earlier this year, students and faculty of Lawrence’s home, Jonathan Edwards College, held a vigil for their friend and classmate. In 2016, Yale students honored Rae Na Lee ’19 and Hale Ross ’18, both of whom committed suicide within four days of one another.

Death clouds hope. It’s the reason why, despite mention of vigils and honors, many who read the above will simply focus on the names, four of them, when in a perfect world there would be none. It’s the reason why the recovery of the living is long and arduous, a backbreaking climb up a vertical and spiked mountain.

It’s psychological. I learned in my economics class that people react much more negatively to losses than they react positively to gains, and when applied here, the logic follows: Hearing that someone died, literally died, packs a much larger punch than glancing at an anti-suicide ad on Twitter. A tiny victory in an expansive war of hopelessness doesn’t do much to inspire.

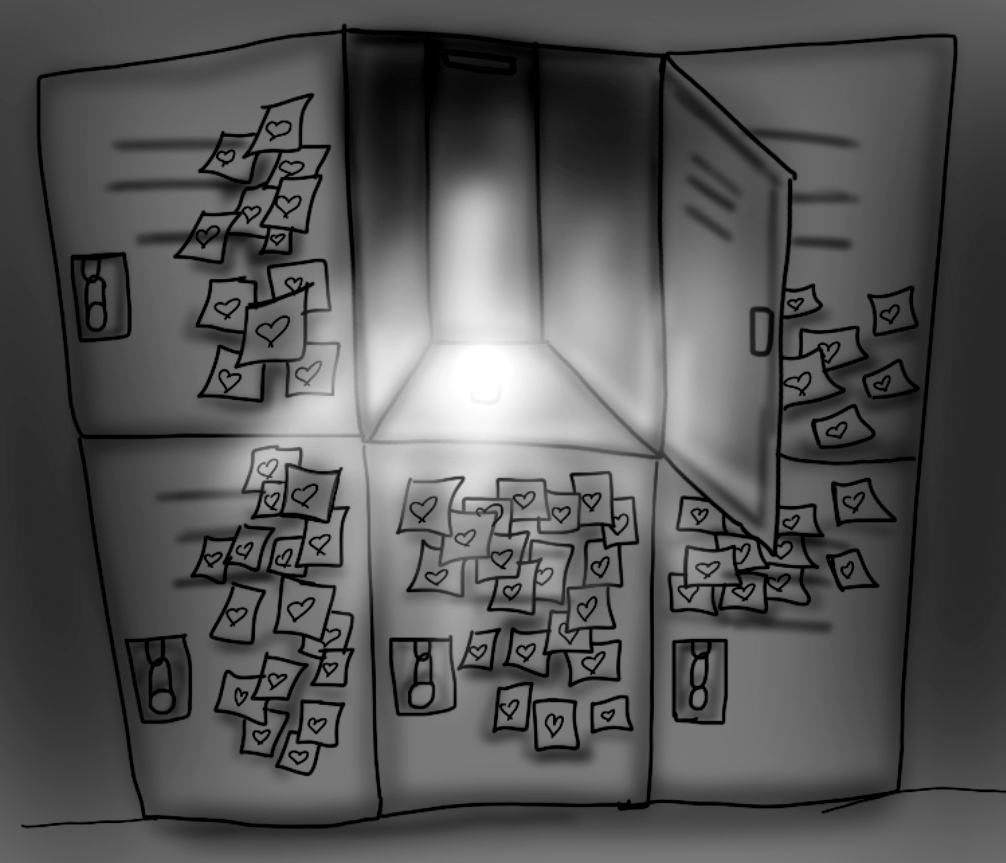

But maybe we can fight this morbid quality with quantity. After news of the student’s death broke at my high school, I was tapping through Instagram stories when I realized almost every single member of my graduating class had posted the sign bearing the simple words: “We Love You.” Snapchat, too, let me see the heart of my community, for hundreds of jewel-bright Post-its, flapping like little birds, all surrounded his empty locker, bearing messages of love and support for a dear friend now gone.

The support found in my little corner of Chicago isn’t isolated. In 2017, the rapper Logic released “1-800-273-8255” as part of his album “Everybody.” That song, featuring Alessia Cara and Khalid, gets its name from the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. According to a report by the organization, calls to the lifeline increased 27 percent to more than 4,573 on the day of the song’s release, and Google searches for the lifeline number increased over 100 percent on the same day. After Logic performed the song at the MTV Video Music Awards, the lifeline reported a record 5,041 calls the day following his performance.

When I first listened to the song this summer, I did a double take and looped the song for a while, listening as the singer first seems to drown in depression, saying over and over how he simply wants to die. But then the song changed, with the singer surfacing and instead encouraging someone, maybe himself, that there’s a light at the end of the tunnel.

I’d never heard a song with lyrics like that before. A lot of modern songs glorify sex and drugs and the music, all featuring words that flow in some variation of “I want your body.” Logic doesn’t do that here. Instead, he speaks not to some everyday object of lust, but to a wider, more real audience, one that hip hop and pop never really seem to address.

A Genius interview with Logic revealed some of the rapper’s inspiration for the second part of the chorus.

“‘And I’ll go on a fucking rant and be like, ‘Tell me what’s positive in your life. Don’t tell me this or that. I want to hear what’s positive in your life,’ Logic said. ‘Can you breathe? Can you see? Can you taste food? Can you walk? Can you this or that?’ These are the things I want to hear. I want to know because I want you to appreciate them … Hopefully they’ll be able to be like, ‘Oh shit, I do feel this way.’”

Can you breathe? Can you see? Can you do anything? In the lonely wake of death, even the living have trouble with action. When my grandparents passed away in my sophomore year of high school, I felt as though someone had slammed a pile of textbooks into my chest, hard and from a great distance. My breath shuddered out of me in little wisps, and for a while, I was still, evaporating into my sadness while my shadow flickered and slowly faded.

The same happened when I heard of the student’s death. One moment I was laughing with my roommate, the next I fell silent, forgetting how to breathe.

A 2018 study by Brigham and Women’s Hospital reported that out of 67,000 college students surveyed, 20 percent of students had considered suicide within the past year, while about that same proportion of respondents reported some form of self-harm.

Nine percent of students surveyed attempted suicide. That’s 6,030 people.

However.

According to a post on my high school’s website, vigils were offered for the student who passed away, with hundreds of classmates in attendance. And at the same time, those of us who had departed in the summer held our own remembrances, and if not for the distance, the entire school would have been covered in our wishes, blanketing our community like a soft and gentle snow.

Meanwhile, at University of Notre Dame, a friend of mine lit a candle for the student in the Grotto of Our Lady of Lourdes. Our high school calculus teacher left a note on the board, saying, “We will not forget you.” And at church, I prayed, prayed for a boy who will be 17 forever, prayed for the legions of souls lost to intangible forces that we fight so hard to defeat.

In death, the living unite. We join hands, we embrace, we sing, we mourn. We work for the cause and for the cure. We love each other, because that’s our greatest power, our greatest offense that manages not to be an offense at all, but an acceptance.

Death is cold, lonely, an icy spear in the chest. And death is not only of the body; it is the defeat of the mind and the spirit. Love is warm, shyly smiling and enveloping us in a soft cloud of brightly fluttering hope. And if we can join hands in love, maybe next time around, the power of death will cower before us.

We love you.

Valerie Pavilonis | valerie.pavilonis@yale.edu .