In the late 1990s, Yale researchers found that ketamine — commonly used as an anesthetic drug and as a popular recreational drug — possesses antidepressant properties when used in small quantities.

A recent Yale study has shed new light on the mechanism behind ketamine’s behavior as an antidepressant. Conducted by the School of Medicine in collaboration with the University of Manchester and the National Center for Post-Tramautic Stress Disorder, the research was published in the journal Chronic Stress on Sept. 21.

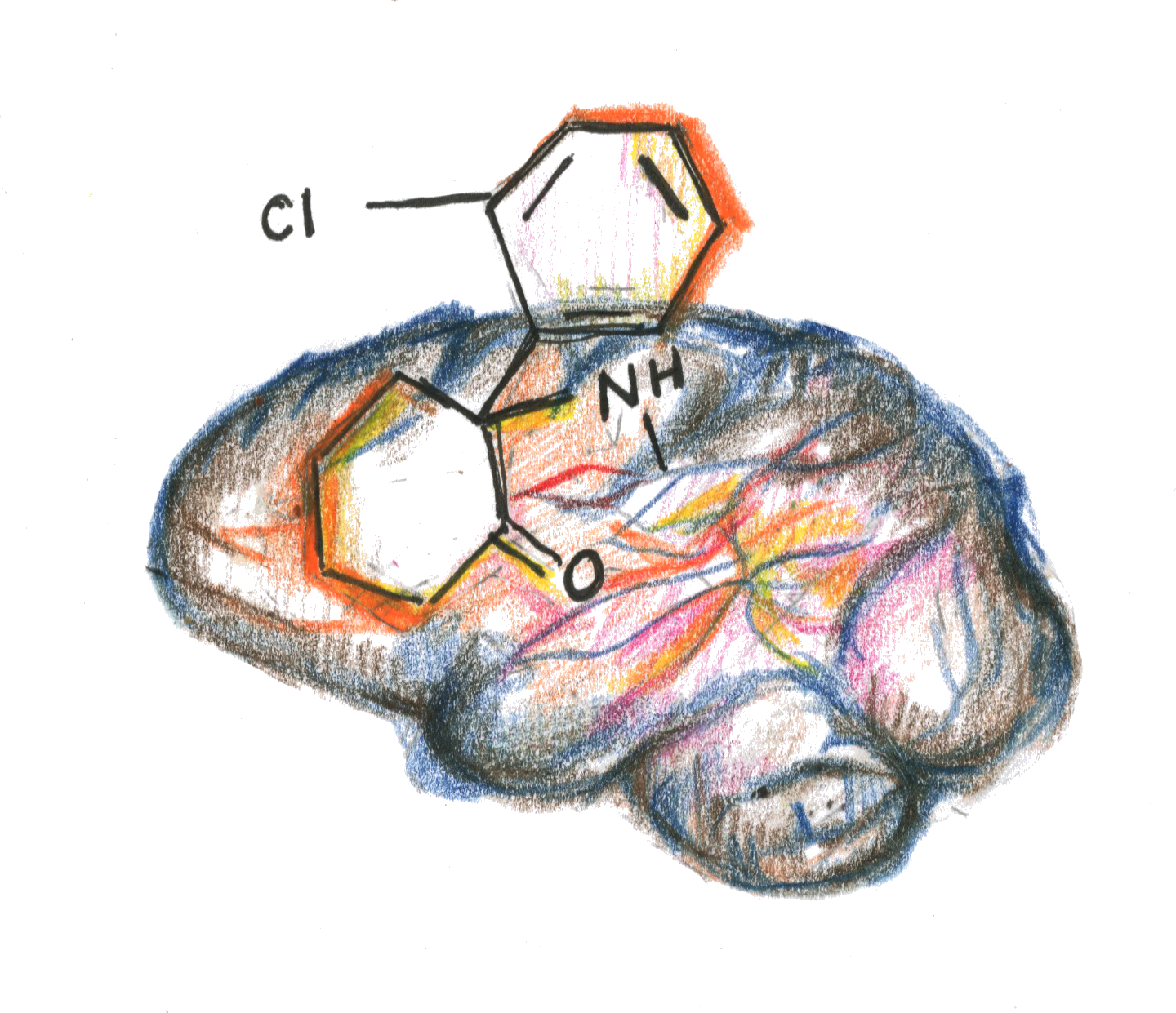

The study found that the antidepressant behavior of ketamine is linked to increased connectivity, which refers to the linking of sets of neurons, in the prefrontal cortex — the region of the brain implicated in decision-making and personality expression.

“Those suffering from depression often have reduced functional connectivity in the frontal part of the brain,” said Chadi Abdallah, psychiatry professor at the medical school and corresponding author of the study. “Our study shows that ketamine treats depression by reversing this reduced connectivity in the prefrontal cortex.”

For the study, 56 unmedicated individuals suffering from major depressive disorder were randomly given either ketamine, lanicemine — an antidepressant drug under development — or a placebo drug. The prefrontal connectivity of the individuals was monitored using fMRI scans, initially at the time of drug infusion and then 24 hours later.

The study led to some unexpected, albeit exciting, results, according to Abdallah.

“During infusion, the amount of increase in the prefrontal connectivity of a subject predicts the extent to which the depression symptoms will improve 24 hours later. This is true for both ketamine and lanicemine,” he said.

According to Abdallah, this finding has far-reaching consequences. For instance, lanicemine is a drug that failed to perform well in clinical trials because it gave mixed results — some subjects responded while others didn’t.

But this study suggests that those who did not respond to the drug may just have not received a large enough dose — and the correct dose can be found by examining the extent to which the prefrontal connectivity increases during infusion.

These findings open the door to a new and more effective form of depression treatment, Abdallah said, explaining that modifying the dosage of a drug based on how an individual reacts to it during infusion will lead to better responses to the drug.

Improvements in existing treatments for depression are necessary for two primary reasons, Abdallah said. First, traditional antidepressants require four to six weeks to start showing significant improvement in patients. Second, almost half of patients do not respond to traditional antidepressants.

“Ketamine is a very promising drug — its effects are highly rapid and long-lasting. The effects from a single infusion dose lasts between seven and 14 days,” Abdallah noted.

However, ketamine is not the ideal cure, according to the researchers. Its side effects, although transitory, range from psychosis and hallucinations to dissociation and depersonalization. Further, the long-term effects of regular ketamine use are not yet known.

“We need to study the mechanism behind ketamine’s use in antidepressant treatments because that will eventually enable us to synthesize better drugs that have the same fast-acting and robust behavior of ketamine but are not accompanied by the negative effects,” explained Teddy Akiki, postdoctoral associate at the medical school and study co-author. “Essentially, we need to develop a drug with the same rapid-action property of ketamine but without the same abuse potential and negative side effects.”

The study’s research team has examined ketamine behavior in the past. For instance, one of their previous studies demonstrated how the antidepressant effects of ketamine could be prolonged if the drug was taken in combination with anti-inflammatory immunosuppressant medication.

In the future, the group plans to study this phenomenon in more detail and exploring ketamine’s use as treatment for veterans with PTSD, Abdallah said.

According to the World Health Organization, depression affects more than 300 million people worldwide, as of February 2017.

Ishana Aggarwal | ishana.aggarwal@yale.edu .